Why You Should Study Emanuel Lasker

The Second Official World Champion

It is no easy matter to reply correctly to Lasker’s bad moves. - William Henry Krouse Pollock

As a result of the far-reaching development in the technique of chess all too many games are drawn if the game is played correctly. In order to avoid this, Lasker manages to maneuver the game to the brink of an abyss by means of a series of theoretically unsound moves. And while he himself is hardly able to hold on, he finally manages, thanks to his greater staying power, to emerge victoriously while his opponent who seemed safe enough falls into the gulf. In this way Lasker wins a victory which he could never have achieved by simply playing a correct, steady game. - Richard Réti.

Emanuel Lasker was the second official world champion. He managed to take the title from Steinitz in 1894, and then successfully defended it against the same in 1896-1897. He would remain on the throne for the longest of any champion — 27 years, and multiple title defenses between. Unlike Steinitz, Lasker never left a “school of thought” behind for the chess world, and therefore his deepest thoughts of the game are in the ground with him. What we have left are mostly contemporary assessments and his own games. So what can we learn from Lasker?

Lasker’s Style

Universal: Lasker’s “style” presents a problem for those among us who love to neatly categorize chess players and their strengths. Partly, it’s because Lasker didn’t write much about chess, so it’s hard to know what he actually preferred. But especially, Lasker’s conception of the game didn’t seem quite as inflatedly grand as, say, Steinitz or Nimzowitsch’s writings would convey; nor was he interested in all of the theoretical debates that the hypermoderns got into about which school was better. This actually reflects one of Lasker’s main strengths: universality as a player. If you’re good at everything, nothing really sticks out. It is difficult to find a weakness in Lasker’s play because he is so well-rounded.

Strategic: Like Steinitz before him, Lasker was a very strong strategical thinker, but soberly avoidant of Steinitz’s excesses — Lasker generally had sounder and more practical ideas than his predecessor (for instance, he tended not to simply send his naked king out to defend itself, and understood tempo much more strongly). While Lasker was not an innovator theoretically, he was quite strong and understood the game more deeply and intuitively than the deepest strategists of both the classical and hypermodern eras of the game. If there is a word to describe Lasker’s own perception of his play, it would be “struggle.” Lasker’s approach to strategy reflected this in his willingness to confront the opponent’s plans directly and cause problems.

Practical: Lasker was not known for his opening theory. While not quite as infamously averse to studying the opening as, say, his heir Capablanca, Lasker rarely tread exciting new ground in the first moves of the game. He would often delay the fight for an advantage until the middlegame, where his tactics and combinatorial skill would shine. If his opponents survived the middlegame, they were often subjected to a torturous endgame where Lasker would grind them down until they finally snapped. John Nunn, in his Chess Course book, remarks that in this respect, the player Lasker most resembles today is Magnus Carlsen.

Counterplay Finder: Sometimes Lasker is saddled with the unfortunate label “psychological” when people try to describe his play. What they meant was that Lasker would intentionally make bad moves to trick his opponents into lost positions; in other words he was a glorified swindler. Whether as admiration like Reti or detraction like Fischer, they were wrong and Lasker’s play has stood the test of time. Modern analysis shows that Lasker was one of the best and most correct of his era, especially when it came to finding ways to set problems toward his opponents. Nowadays, we just call this “counterplay”. The moves Lasker chose were based on his fine-tuned assessment of the positions. Lasker shows, more than any other player of his era except possibly Capablanca or Alekhine, how you can find resources in positions to stay alive or even turn the entire game around.

Defensively Responsible: More than most players, Lasker was an extremely strong defender, which made him difficult to defeat even when one had a winning position against him. It is this particular skill, combined with his ability to find counterplay, that helped Lasker finish ahead of Capablanca in many tournaments long after he had given up the title.

Endgame skill: Lasker was one of the strongest endgame players of all time, managing to outplay the likes of Capablanca and Rubinstein. While his endgames aren’t usually subject to the same kind of praise as those two, they are nonetheless extremely impressive.

Fighting: If you asked me to boil down what makes Lasker such a strong player compared to the others, it’s that he’s a natural fighter. His games show that he wasn’t afraid to grapple and get down in the dirt and mud and find the right moment to slug his way through to victory, even in the endgame — even when it was drawn. Lasker saved and took many additional half-points thanks to this strong mentality.

Tactical: Lasker’s earlier career features many beautiful games with textbook combinations that are now part and parcel of many chess tactics books.

Lasker’s Opening Repertoire

As White: Ruy Lopez, Queen’s Gambit

Lasker wasn’t an experimenter in the opening. He kept to the tried and true lines of his day. Occasionally, he would play something different, but by-and-large, 1.e4 was his workhorse, and he used 1.d4 as a backup.

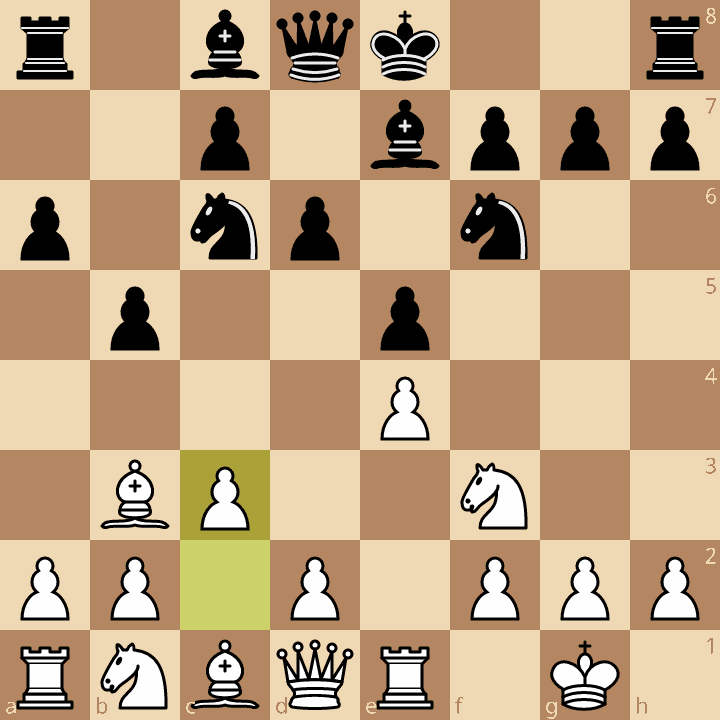

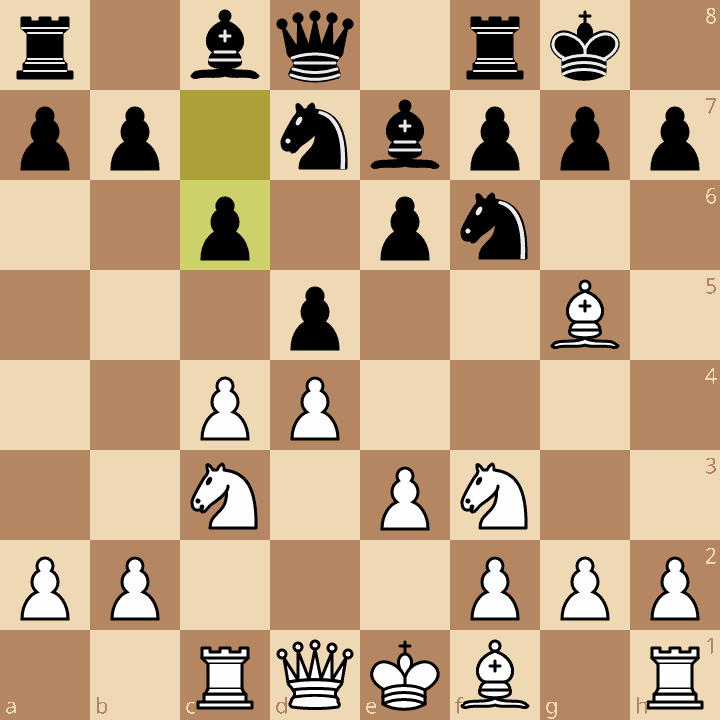

The Ruy Lopez opening was Lasker’s usual weapon in the open game. Lasker often played down the very main line if given the opportunity: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.O-O Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 d6 8.c3

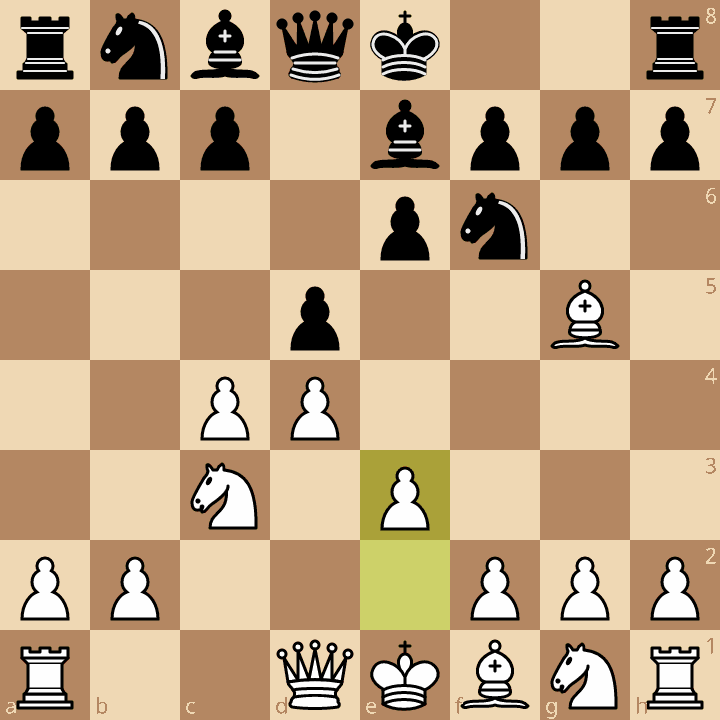

The Queen’s Gambit was Lasker’s backup weapon. Theory had grown quite a bit, and Lasker was usually contented with the popular QGD setup after 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5 Be7 5.e3

As Black: Open Game, QGD

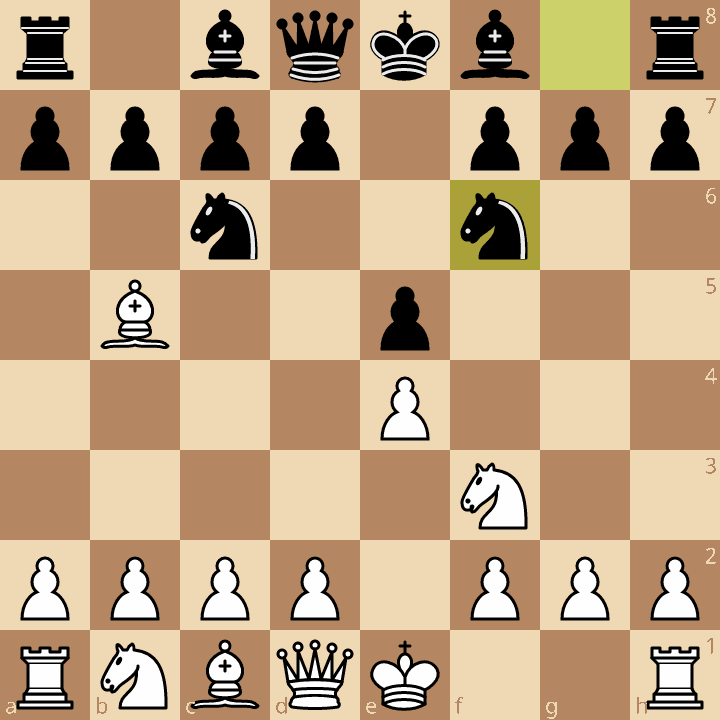

Against 1.e4, Lasker usually preferred the Open Game with 1…e5. Against the Spanish (2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5), Lasker most often chose the Berlin Defense with 3…Nf6. Against the Italian (3.Bc4), Lasker played both the Giuoco Piano (3…Bc5) and the Two Knights Defense (3…Nf6).

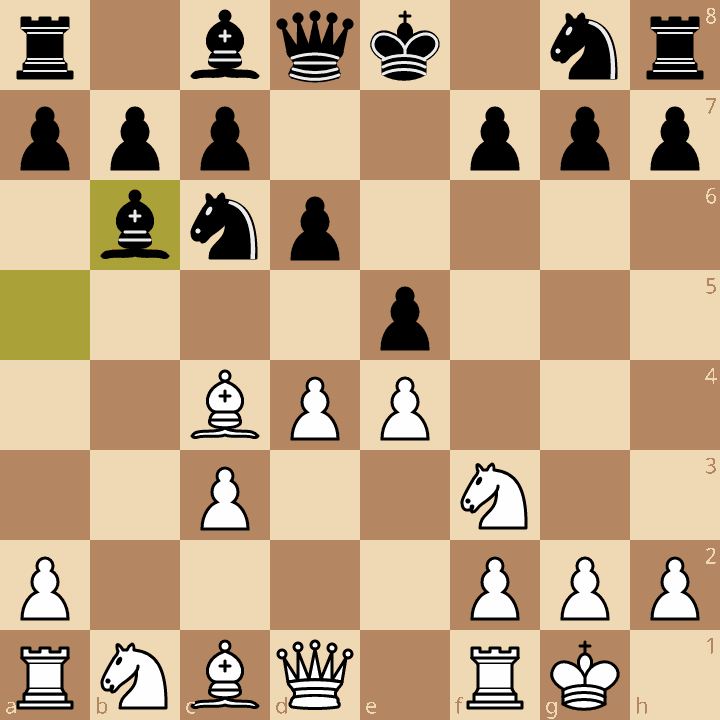

Lasker has a particular variation of the Giuoco Piano’s Evans Gambit named after him, after 4.b4 Bxb4 5.c3 Ba5 6.d4 d6 7.O-O Bb6:

It reflects his practical approach to the game: after 8.dxe5 dxe5 9.Qxd8+ Nxd8 10.Nxe5 Be6, White has no attack, and Black can organize a defense — the exact nightmare situation for an Evans Gambit player.

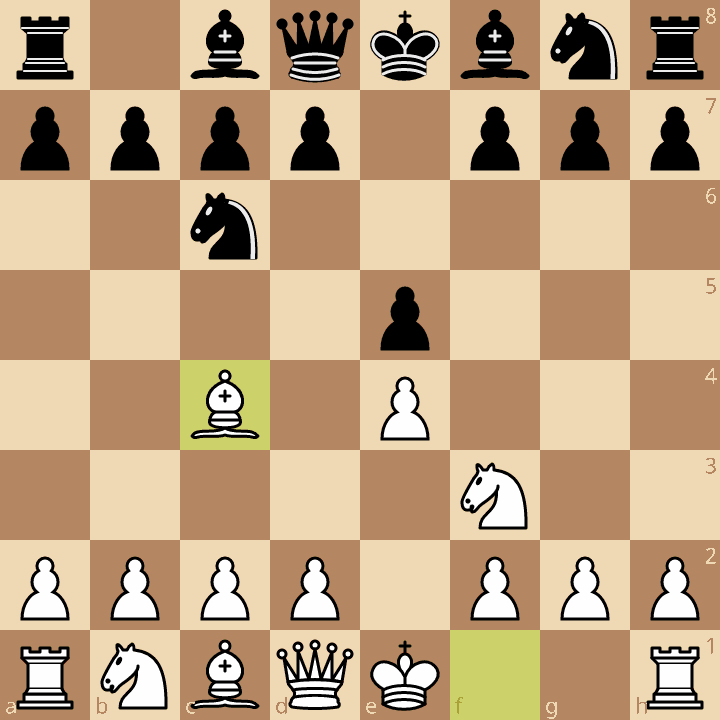

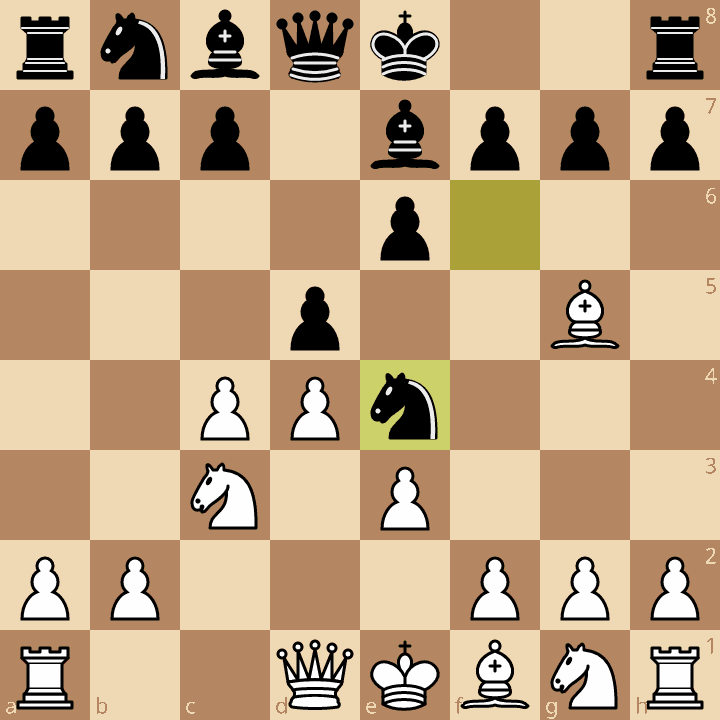

Against 1.d4, Lasker usually went for the Queen’s Gambit Declined. Lasker usually went for the main line of the day with 1…d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5 Be7 5.e3 O-O 6.Nf3 Nbd7 7.Rc1 c6 (also known as the Orthodox Defense)

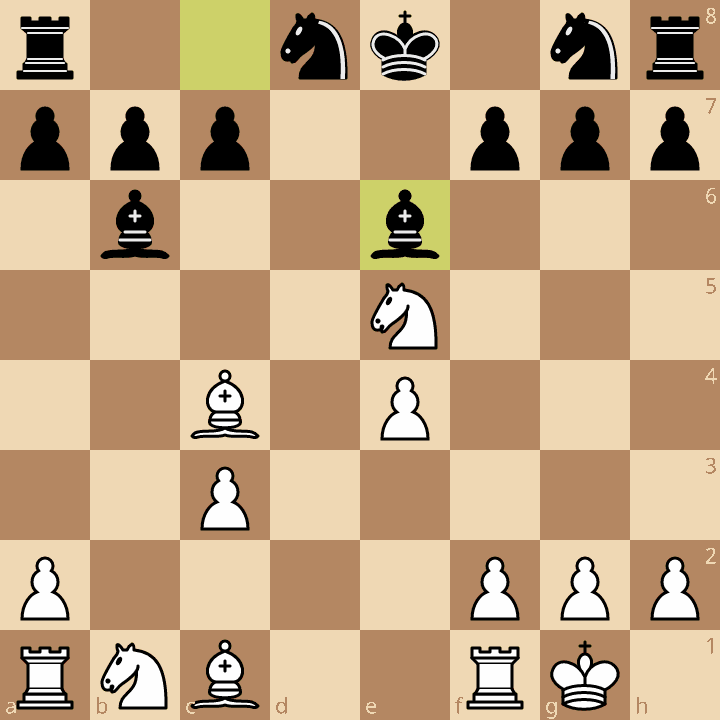

He even has a particular defense named after him after 5…Ne4. The Lasker Defense directly addresses Black’s space issues by initiating piece trades. Nowadays it’s considerably old-fashioned, but many of Lasker’s games feature this line.

Lasker’s Weaknesses

Too(?) Practical: Lasker is hard to peg a weakness for. One way Lasker might have improved would be in his opening theory — but I suspect that the same thing that caused him not to look for the cutting edge in opening theory is also what that made him so dangerous in the middlegame — preference for the practical struggle.

Overpressing for a win: It happened on occasion that Lasker would push too hard for a win by initiating complications when the position called for maintaining the status quo or keeping things simple. This impatience is rare, which makes it stand out in some of his losses.

Conversations: What are YOUR thoughts about Lasker?

Lasker Resources

Ben Finegold’s Great Players of the Past series is always instructive and entertaining:

(Some) Illustrative games

Lasker - Bauer, 1889 - Lasker uncorks an immortal double-bishop sacrifice that has since become an extremely instructive tactical motif featured in many books.

Pillsbury - Lasker, 1896 - A triple rook sacrifice and an immortal game against the burning chess supernova Pillsbury.

Lasker - Tarrasch - 1914 - A famous endgame that now shows up in tactics books all the time.

Alekhine - Lasker, 1924 - Lasker outplays a future world champion three years after losing the title to Capablanca. Very emblematic of Lasker’s practical ability against one of the world’s best attackers.

Euwe - Lasker, 1934 - 66-year-old Lasker sacrifices a queen(!) for a rook and knight against another future world champion.

Lasker - Capablanca, 1935 - A classic attacking game between two former world champions. Capablanca never stands a chance here.

Lasker - Euwe, 1936 - Lasker plays a cheeky tactic to beat the world champion.

Amazing article. I think that reason so many people in his era and even later fell back on the psychological explanation is that they didn’t fuunderstand what was happening in his games.

In most of his games if you take the position after the opening his play is completely modern. His understanding of dynamics and the various trade offs between material structure and activity was at least a generation ahead of his time.

His games feel completely modern in terms of middle and endgame play.

Lasker's counterplay-finding approach is basically applied game theory before the formal frameworks existed. What's interesting is how his "practical" style mirrors what modern game theory calls mixed strategies, where deviating from "optimal" moves creates informational asymmetry. The comparison to Carlsen makes sense becasue both understood that human opponents don't calculate perfectly, so positions with more decison nodes favor the better calculator. The fighting mentality you mentioned is really about maximizing expectd value over board positions rather than just objective evaluation.