Classical Game Recap: A Neat Trap vs the London System after 2...c5

And why taking your time is important!

It’s round 2 of the Sacramento Team Championship. After facing a tough loss in the first round, I was ready to play hard for a win this week. However, the game was decided by an early blunder by my opponent, and unfortunately he didn’t appear to take the game very seriously, and didn’t put up as much of a fight as I think he could have, even with a 1000-rating point difference. Determined to at least let the game be instructive to others, I’m annotating the parts of it I found the most interesting — though I admit this isn’t the most interesting chess game. I think that my opponent could have considered many of the positions in a different way, and that there’s some cautionary tales about making moves without calculating at all.

Time Control: 60 minutes with 15 second increment per move.

White: Dwight Jackson (612 USCF)

Black: Me (1658 USCF)

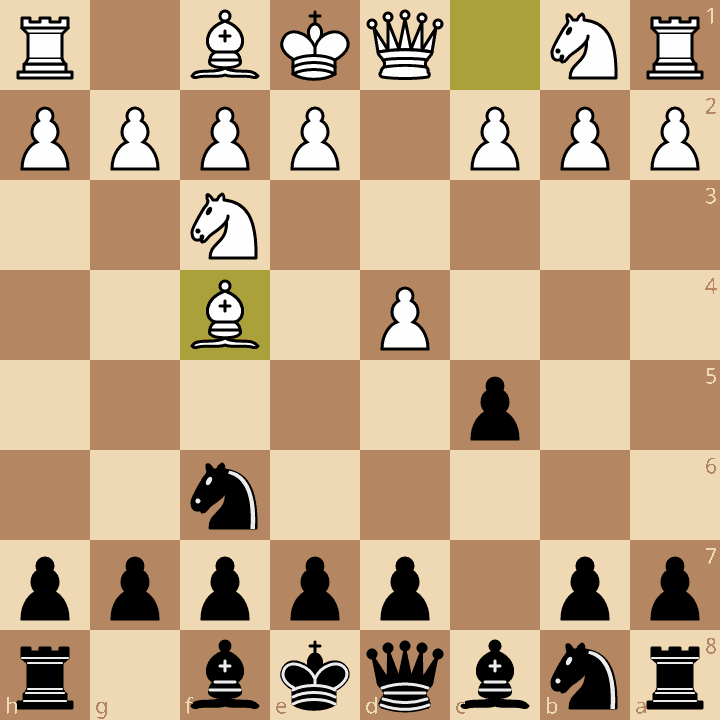

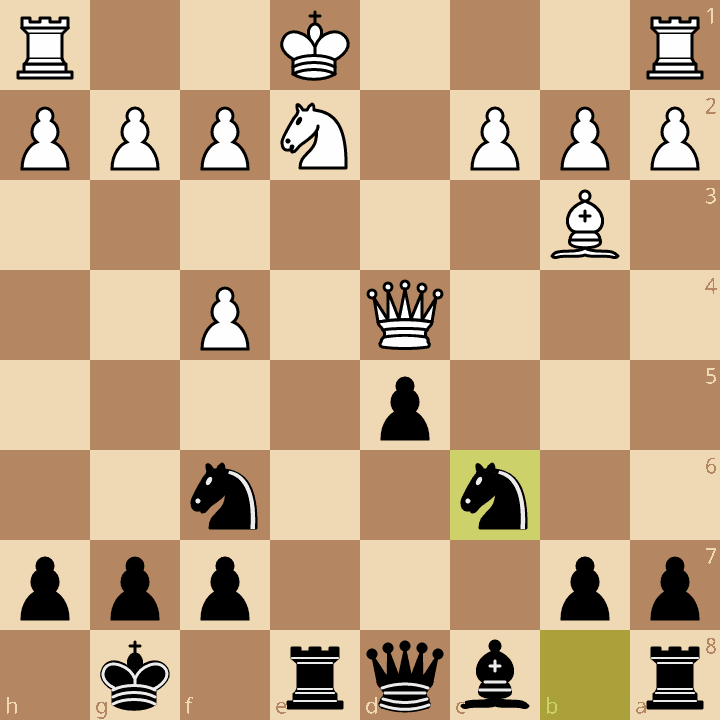

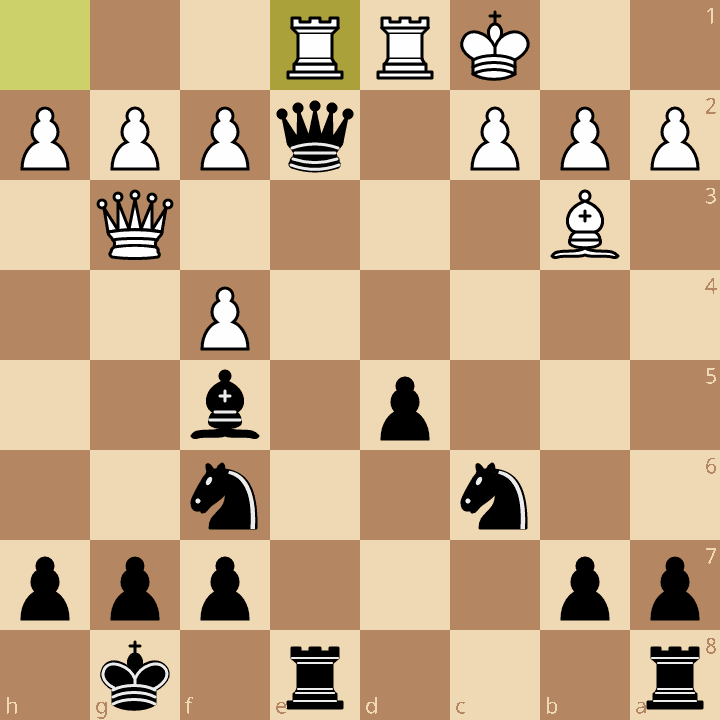

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 c5

This line is known as the Spielmann-Indian Variation of the Indian Game. It looks a bit odd at first, but the idea is to either play a pseudo-Benko Gambit after, say 3.d5 b5, and to otherwise put pressure on White’s center before they’ve had the chance to get in 3.c4.

3.Bf4?!

The intent by White was to head into a London System, but in this position where a trade on d4 is already threatened, there’s a snag. Instead, 3.d5, 3.e3, 3.c3, or 3.c4, or even 3.cxd5 are playable.

3…cxd4!

Black is even slightly ahead here, because of the problem of losing tempo recapturing the pawn. This is a hallmark of weaker players: They tend to give their opponents free moves. The rest of the opening phase of this game shows this even further.

4.Nxd4??

Instead, 4.Qxd4 was called for. After 4…Nc6 5.Qd3, Black is slightly ahead. Alternatively, though it gives up the bishop pair in the process, White can regain the pawn via 4.Bxb8 Rxb7 5.Qxd4.

4…e5!

The trap is executed. Black wins a piece for a pawn.

5.e3?!

5.e3 is a passive move. Though the position is bad for White, this is one of the slowest ways to respond and results in White getting a doubled pawn and even less compensation at that. After 5.Bxe5 Qa5+ (the point of 4…e5) 6.Nc3 Qxe5, White at least has a pawn to show for his trouble. Black’s position is still dominant, but if one insists on playing on in this position as White, at least there’s a bit more of a winning chance.

This was the first time I noticed that my opponent spent time to think. Our first few moves he was blitzing them out. If he had spent time earlier on the third move, he may have found out why cxd4 was played, but the idea may be a bit subtle for players rated in the 600s. But even on the 4th move, if he looked ahead even 2 ply ahead he may have noticed the Qa5+ resource that allows Black’s bold pawn push on the previous move. To become stronger, you have to look ahead — even a minimal glance a few ply ahead is enough to gain hundreds of rating points. You’ll avoid gross blunders like this.

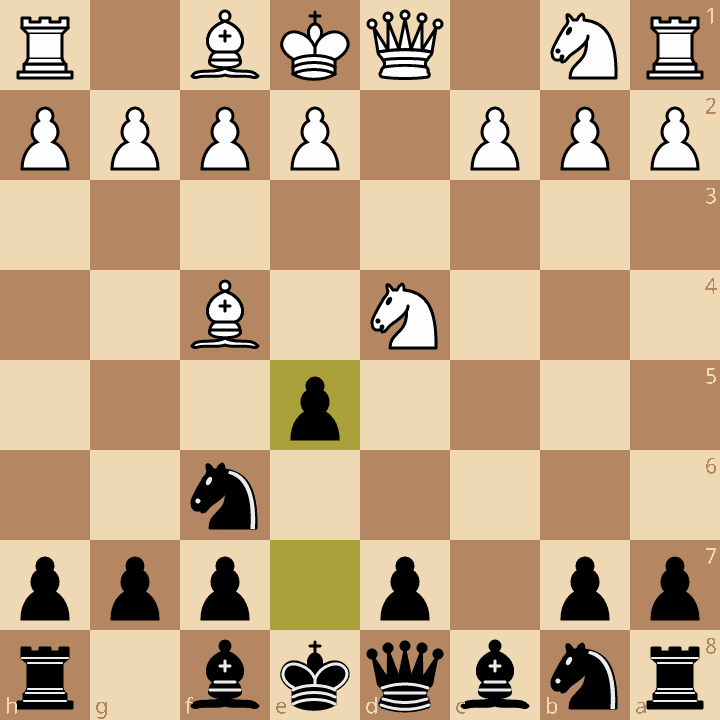

5…exf4 6.exf4 Bc5 7.Nc3 O-O

7…Bxd4?! 8.Qxd4, following the principle of making exchanges when you’re already up material, isn’t as strong. Black is still winning because of the material advantage, but allowing the queen to develop and clearing the queenside back rank for White isn’t nearly as testing. I castle because I want to continue activating my pieces. Re8+ is now threatened.

8.Bc4

8.Be2 doesn’t lose tempo and allows White to castle without trouble.

8…d5

Winning that tempo, increasing my ability to develop since now by queenside bishop is opened up.

9.Bb3

9.Be2 was probably the lesser evil.

9…Re8+ 10.Nce2 Bxd4 11.Qxd4 Nc6

Winning another tempo. A lot of this game can be explained by White basically giving me every opportunity to get “free” moves in that increase my advantage.

For the first time, my opponent spends a few minutes on his move.

12.Qd3 Qe7

I put pressure on the e2-knight and prevent White from castling (on pain of losing another piece). However, my opponent only spent a minute and didn’t realize the threat (or perhaps had given up a long time ago and was just making moves to go through the motions).

13.O-O-O Qxe2 14.Qg3 Bf5 15.Rhe1??

This was one move I had anticipated. Since this move was possible, I had to calculate my response to it after 14…Bf5, which allowed it. If your opponent has a threat, sometimes you can let them execute it because you have a good response. But you have to first account for that threat in your calculations — otherwise you’re just running an unknown and unnecessary risk.

15…Qxe1!

My opponent at this point muttered “oh that’s cute” and made another move.

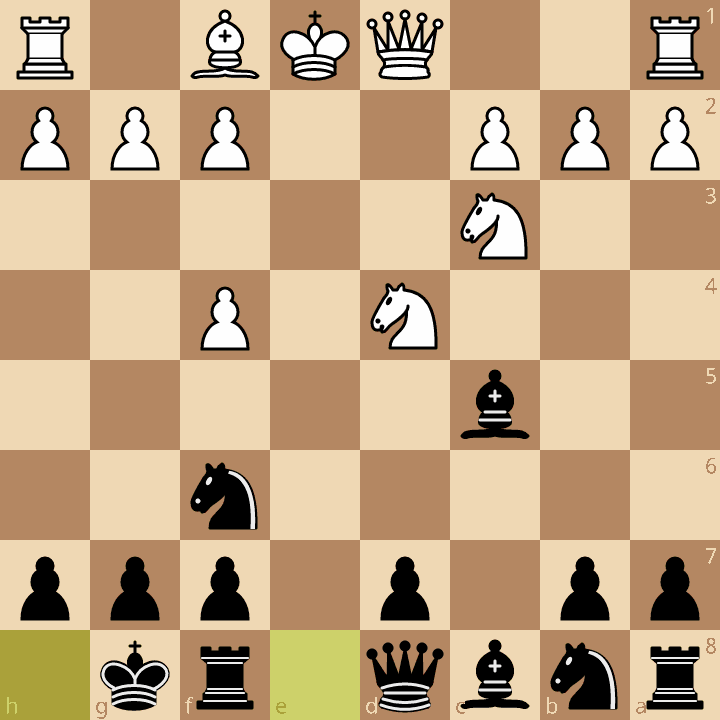

16.Qf3

If 16.Rxe1?? then 16…Rxe1+ 17.Kd2 is forced. 17…Ne4?! 18.Kxe1 Nxg3 is more than sufficent to win and is what I was going to go for, but Stockfish says 17…Rae8 is even more winning. It makes sense, since White is dangerously low on squares for the king, and Black should have a mating attack.

16…Qe4

At this point, any trade is good for me, so I’d rather get into the endgame as soon as possible to simplify the position.

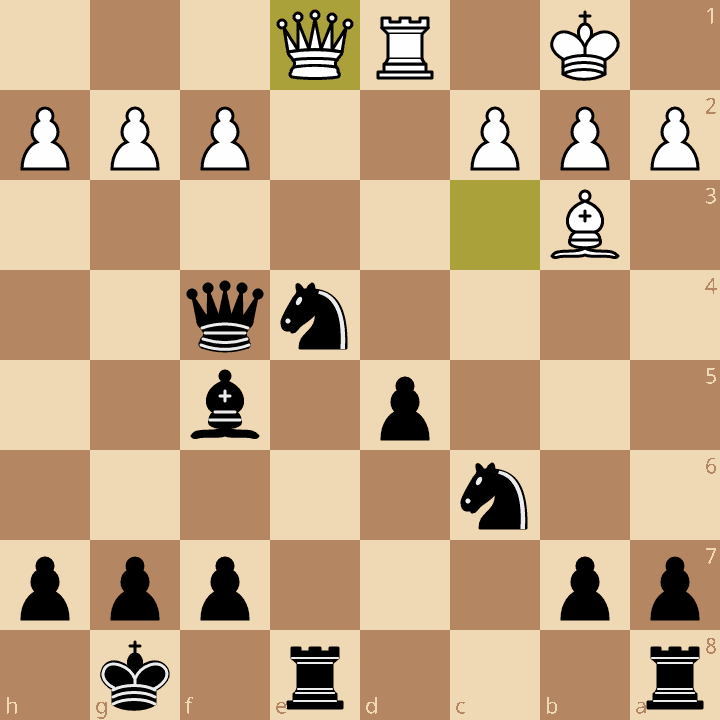

17.Qc3 Qxf4+ 18.Kb1 Ne4 19.Qe1

Now Black has a mate on the board (mate in 7 with best play), and the win is easy.

19…Nd2+ 20.Qxd2 Qxd2 21.Rxd2 Re1+ 22.Rd1 Rxd1# 0-1

Takeaways:

Beware of making familiar moves in an unfamiliar opening. The alarm bells should go off that after 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 c5 that the d4 pawn is actually under attack and that 3.Bf4 (trying to get into the London) allows that pawn to be captured; because White must recapture with a piece, it’s important to notice whether Black gains anything by White’s taking the pawn. Supposing this was seen in advance, a different move might have been chosen by White.

My opponent didn’t spend time when he really should have. I got a lot of extra pieces simply because he didn’t look ahead even a couple ply. Even though I had the easier game and most any choice I had was between two ways to win, I spent more time than he did, simply out of habit. Build this habit and your chances of blundering may decrease dramatically.

Gif of the full game: