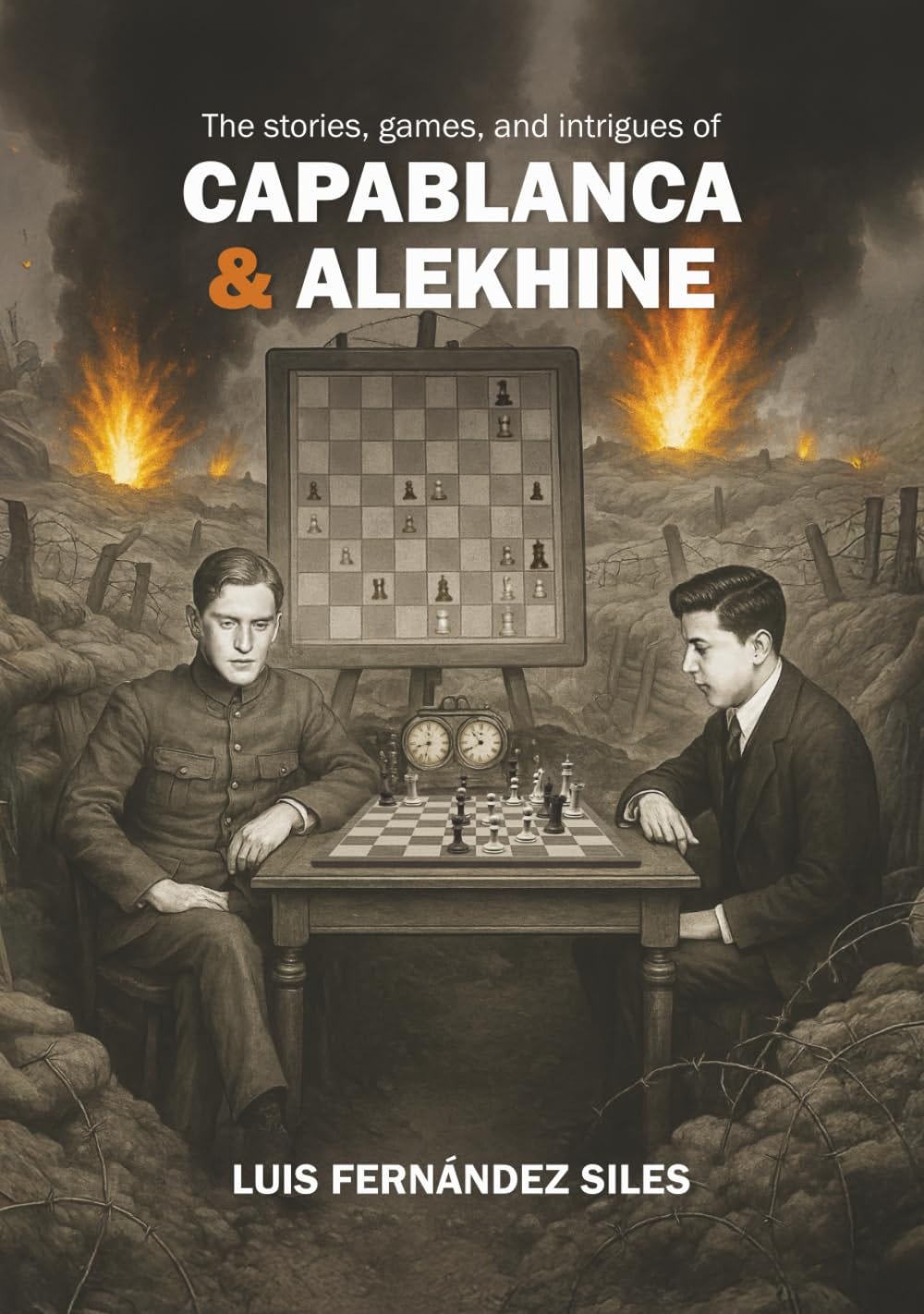

Book Review: The Stories, Games, and Intrigues of Capablanca and Alekhine by FM Luis Fernandez Siles

An accessible, club player-friendly recapitulation of the Capablanca-Alekhine rivalry

Thank you, Luis Fernández Siles for sending me a review copy.

Of the pre-FIDE era of World Champions, there are no two more biographied players than Jose Raul Capablanca and Alexander Aleksandrovich Alekhine. Both players are considered to be among the strongest the world has ever seen. Both players were, for a time, the best player in the world and worthy holders of the World Champion title. And both players lived during an extremely influential period of time in chess theory development known as “hypermodernism”. Both players denied their own membership in this group of renegade romantics, and were considered to be the pinnacle of the “classical” school of chess, though, as history shows, the truth is rarely ever that simple.

Despite both being world champion alumni, premier “classical”-school adherents (at least by stereotype), and the greatest players in the world of their era, the difference in their style from one another is striking, even just as their lives and upbringing differed. Because of this, they make for natural foils in the historical chess narrative. While Nimzowitsch, Reti and Tartakower wrote books, Capablanca and Alekhine became world champions (well… they too wrote books, especially Alekhine. I digress). And as far as chess history goes, this period from the 1910s to the 1940s represents a treasure trove of rivals, their ideas, their quarrels, and their games.

Capablanca and Alekhine are the eponymous protagonists of FM Luis Fernandez Siles’s (Maestro Luisón) recap of their part in 4 decades of chess history, tournaments, championships, opening theory and rivalry. The book is written in roughly chronological ordering of tournaments and other major events, though on infrequent occasion, there are detours to interesting games that don’t quite fit into the main narrative. FM Siles gives a bird’s eye view, with informative recaps of events between tournaments, beginning with Capablanca and Alekhine’s first games in St. Petersburg, 1913, all the way to their last games against one another at AVRO 1938. Along the way, the Cuban and the Russian-French go from casual acquaintances to bitter rivals, and Siles gives the story as to why. It’s nothing ‘new’ per se, but it’s nice to have the whole narrative from beginning to end with all the major story beats in a single volume, rather than having to scour all the tournament books and chess journals and articles that have been written over the years. In this way, The Stories, Games, and Intrigues of Capablanca and Alekhine represents a helpfully-distilled version of the story.

Notes about the book:

Capablanca and Alekhine is self-published. It was first published in Spanish and has been translated into English. In general, the translation is very good. The hardcover is nicely bound, and the page design is handsome. The pages on this one are really thick and feel very high-quality. There are many diagrams for each game, which are presented in two-column format. I did not find a single reference to any centipawn numbers for evaluations; Siles sticks to classical symbols and/or plain English to convey the evaluation of a variation (e.g. the way it should be done for most books). Tournament tables and greyscale photos appear in generous amounts. Where applicable, Siles cites his sources (footnotes, not endnotes). Luisón states in the “author page” at the back of the book,“This is his first book, but it promises not to be his last.” I’m looking forward to more.

This is a really great addition to any chess book collection.

During our trek through time, we meet some other characters along the way. For instance, World Champion Emanuel Lasker (he loses the title to Capablanca in 1927), World Champion Euwe (he wins the title from Alekhine in 1935, but loses it back to the same in 1937), and future-World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik (perhaps the strongest player by the time Alekhine regains the title, but unfortunately never able to face Alekhine in a match despite multiple attempts at negotiations).

But not just champions show up and get a little time to shine. Tarrasch, Reti, Bogoljubow, Keres, Fine, and Reshevsky also make appearances. In this way, the reader gets acquainted with other major figures and, in most cases, some of their fine wins against one another or even against Capablanca and/or Alekhine. I find the transition of the old guard to the upcoming Soviet dominants and their American opponents rather striking in the latter half of the book. While the focus remains on the two champions, there are so many other up-and-comers in history that Siles correctly intuits that it would be wrong to exclude them from the narrative.

Since Siles goes tournament-by-tournament, one can also really get a sort of geographical roadmap to go with all the history lessons. This is one of the periods where I think chess journalism really started to take off, which may explain why the narrative can be given so richly again today. Alekhine seems the progenitor of many modern traditions in chess, and the storied tournament book is one major contribution. To be sure, he didn’t invent them, but he’s called the father of modern analysis for good reason! This makes Alekhine an important source of information as to why he made certain moves. This assists in Siles’s storytelling when analyzing games that Alekhine wrote about. Kasparov’s comments (mercifully, not his deep analysis) are also cited on occasion. While not quite a best-hits compilation, this book shows many famous games that follow an organic and historical narrative thread, and as such acts as an excellent contribution to the corpus of modern game collections.

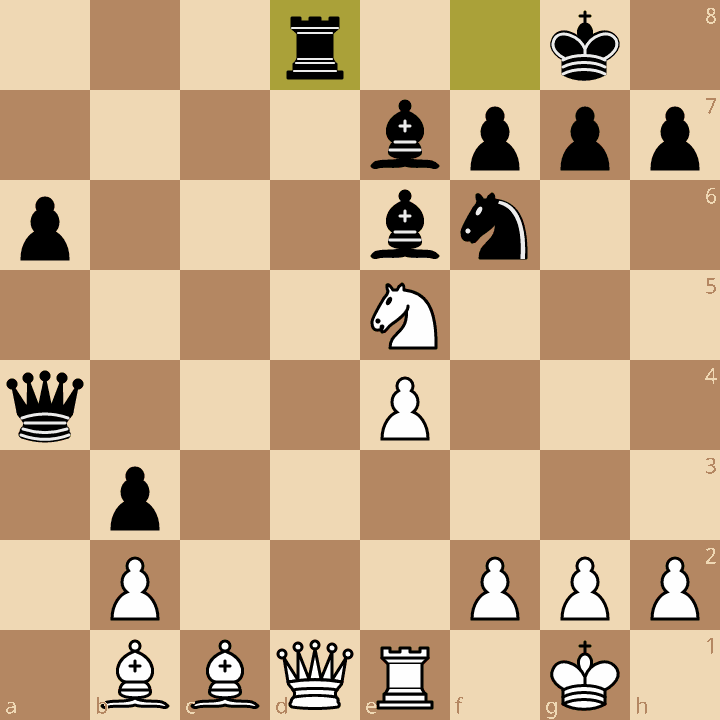

Siles’s analysis style is light on computer variations (he used Stockfish 17) and is oriented toward the beginner-to-intermediate player (I’d say, in terms of chess ratings, 1000 to 1200 at the bottom end, 1600 to 1800 at the top end). He gives cogent advice and quick notes about the strategy and/or tactics behind a player’s move, without getting into the thick weeds of opening theory or (with few exceptions) endgame lines. Because of this, the games are relatively quick to be played through. Earlier in their careers, the choice of opposition simply wasn’t as strong or evenly matched, which makes Capablanca and Alekhine’s games extremely instructive for the learner. For instance, an early example from St. Petersburg 1913:

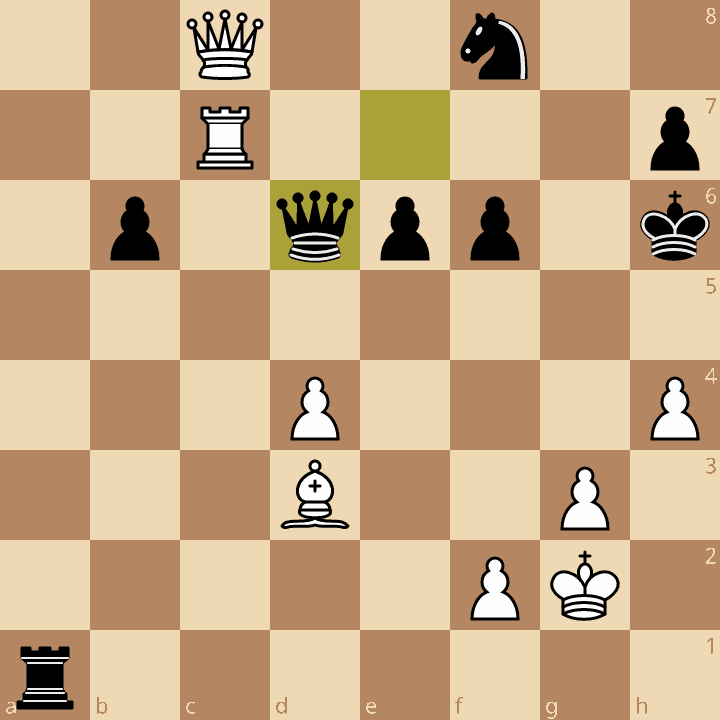

From this position, play continued as follows: 20.dxe5 dxe5 21.Nxe5 Rxc1 22.Bxc1 Rd8

While the book isn’t presented as a pure improvement guide, or even something to read in order to improve, there’s plenty to draw from for the attentive reader. The depth of the given analysis is intentionally low, and Siles keeps only the clear lines in order to increase one’s understanding of the positions and support his notes. Players looking for more technical analysis may be somewhat disappointed by this, but for the vast majority of readers, this is the perfect level of explanation and will help them avoid variation fatigue. Siles mentions in the introduction to the book that his aim was to provide educational analysis and history in a single book, and in my opinion he has largely succeeded. It would be difficult to think of another book that does so well at wearing both hats.

Speaking of games…

There are 85 games and fragments (mostly games) that Siles has chosen to provide. The selection of games is very instructive. I noted down several which I particularly enjoyed. For one, Siles includes one of Capablanca’s early losses: That to Emanuel Lasker (then champion) at St. Petersburg 1914, where Lasker uses the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez to take first place in the super tournament.

Siles’s given variations aren’t deep, but that doesn’t stop it from being both an instructive and inspiring endgame for improving players, and the written analysis and explanations are still helpful for understanding the “over-the-board” story of the game regardless.

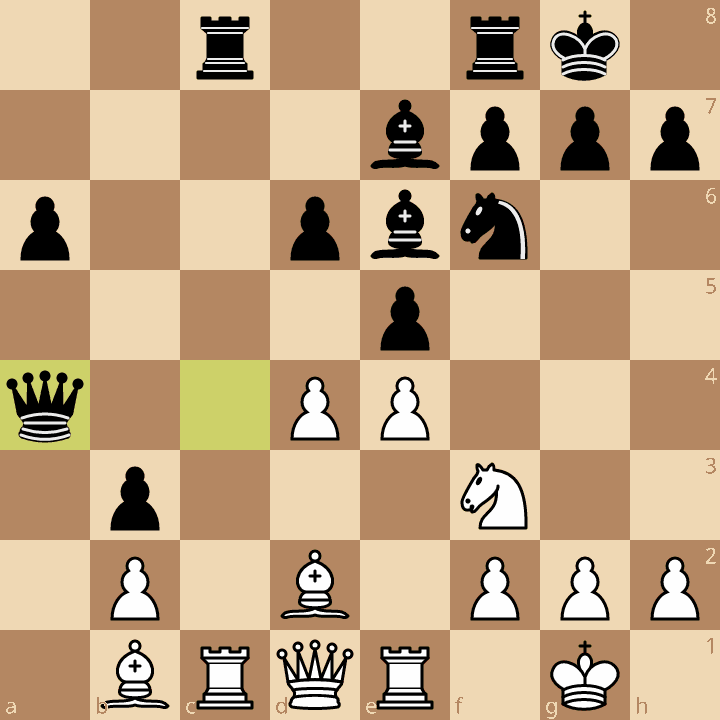

Lasker shows up every-so-often in the narrative and never fails to entertain, even when he’s on the losing side of tactical endgame brilliance by Capablanca (such as round 11 of the 1927 World Chess Championship, at the end of which match Capablanca would receive the crown):

However, Capablanca’s reign was not fated to last for long.

Siles finds that Alekhine determined that his chances of winning the title from Capablanca were non-zero after ruminating about a draw that he was able to make against the World Champion during the 1924 New York supertournament, despite the poor situation he had obtained from the opening. Incidentally, Alekhine would lose another game to Capablanca at the 1927 edition of the same tournament, shortly before the impending championship title match, leading to speculation that the match would become a blowout in the Cuban’s favor.

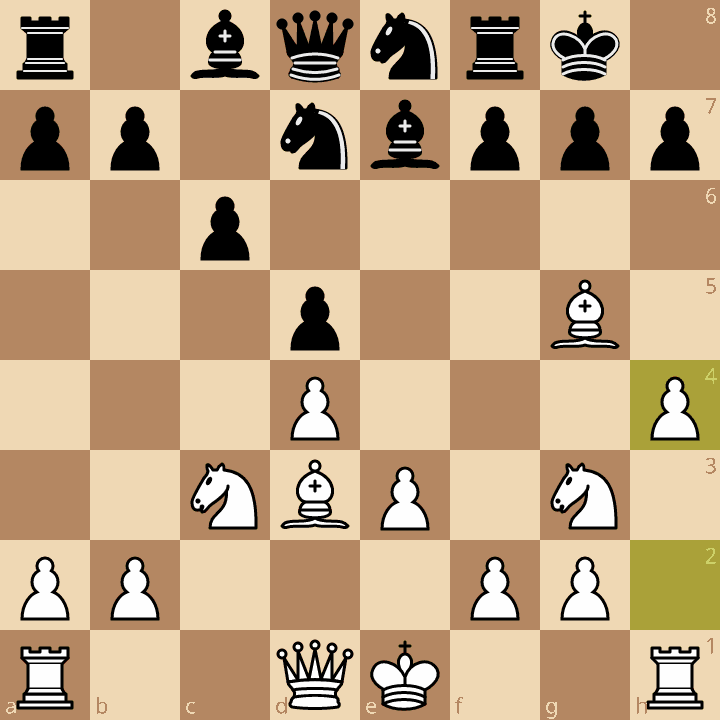

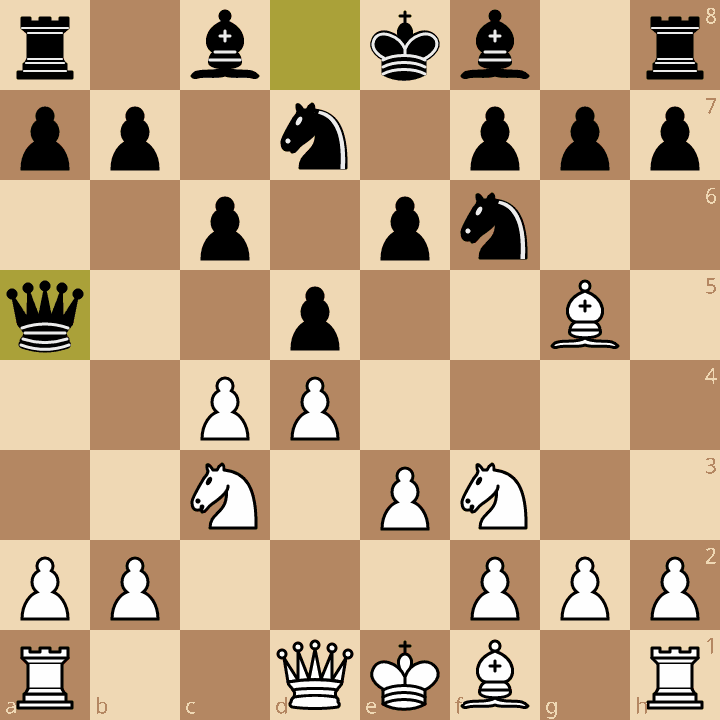

The 1927 World Chess Championship has an infamous reputation due to the frequent use, by both players, of the Cambridge Springs Variation of the Queen’s Gambit Declined:

Perhaps because of this reputation, I had gone into the games from this match (having not really paid much attention to them before due to their aforementioned reputation) expecting a lot of boring positions. However, Siles evidently disagrees, as he chose to include 15(!) games from 34-game match in the book, including multiple incredible draws. I’m glad he did.

To start, these games weren’t actually boring. Additionally, both players made changes to their plans, game-by-game as they sought to find a weakness in one another’s armor. And I find it fascinating how despite the players’ clearly obvious differences in play style (Capablanca the intuitive strategist; Alekhine the calculating mastermind), they chose this exact opening to conduct most of their debates. Because this variable is essentially removed from consideration, you can really get a feeling for the players’ different approach to the game in general.

Theory has moved on quite a bit since this match, but there are some instructive moments throughout (see below, Game 32 for instance), and this became, for me, my favorite part of the book, particularly as Alekhine’s indomitable will to win was show to be stronger than any of Capablanca’s talent would be able to overcome. The match was not without twists and turns and rallies to even the score by both parties, and Siles relaying of the story of the championship is riveting. It really is the best part of the book.

The 1927 World Championship is the half-way point of the book, and the half-way point of Capablanca and Alekhine’s rivalry. From here their relationship begins to degrade, and Siles keeps track of all of it. Alekhine’s behavior during this period was anything but sportsmanlike, and he would evade direct communication with Capablanca and demand high fees for appearances at tournaments where Capablanca also competed. Alekhine would also half-heartedly engage in a few title defenses against Bogoljubow, though even he himself didn’t take them very seriously.

It is particularly shocking to see how out-classed Bogoljubow, one of the world elite, was against Alekhine in their matches:

Siles shows how dominant Alekhine became up until he lost the match against Euwe in 1935, and shows one game from said match where the reader may be prompted to ask, alongside all the historians, “What was he drinking?”

When Alekhine comes back to retake the title in 1937, he is still a brilliant player, but it’s clear that he has slowly begun to decline. In the meantime Siles takes pains to show how Capablanca was progressively working on a comeback himself, still seeking a rematch for the title, despite Alekhine’s onerous (and karmically-charged) demands and probable evasions of serious competition.

Of course, there are other players who were rising at the same time, and Capablanca and Alekhine face them as well and begin to take their lumps. This period of time, from 1937-1946 contains a number of brilliant games that are mostly left unexplored; 1938 was the last time that Capablanca and Alekhine met over the board. During the AVRO tournament at which these final games took place, Botvinnik (and Fine, and Keres) had clearly risen to become a legitimate challenger to the throne. Nevertheless, due to World War 2, a match would never take place. Capablanca would die in 1942 due to complications from hypertension.

The book does give a short mention to Alekhine’s antisemitic writings during his time in Nazi-occupied Europe. By this time, however, Alekhine was certainly past his prime. Siles shows this with the penultimate game of the book, where Alekhine stumbles into a draw against future Spanish GM Arturo Pomar (As Siles notes, Pomar appeared doggedly determined to get a draw, even when he could push for a win). In any case, once Capablanca dies, the rivalry with Alekhine died with it, and so from a narrative angle it makes sense not to include most of these games. Alas, Alekhine was not long for the post-WW2 world in any case, after having ingratiated himself toward the Nazi regime (for more information on this part of Alekhine’s life, consider reading Taylor Kingston’s Chess in the Third Reich). His untimely death in 1946 is still shrouded in mystery, but the author gives his reasonable speculation as to what happened. It’s a strange ending to the life of one of the more interesting characters in the world of Chess.

The Stories, Games, and Intrigues of Capablanca and Alekhine is a highly educational read, and delivers on basically everything that its title promises. It slots very nicely into the leisure-reading chess history category with a healthy helping of master-level games to play through, and there are copious diagrams so that you can follow along without a board, (although in my opinion you should always use a board if you want to understand games more deeply). I personally do think the analysis could have gone deeper in general, and on many occasions a variation or move in a given position is stated to be “interesting” but without further comment or analysis as to why, exactly. However, for the vast majority of players and readers, Siles gives the right kind and amount of analysis. The games chosen are instructive and inspiring, especially if you have never seen them before. At all times, the book was a joy to read and play through, so much so that it is difficult not to recommend it to anyone looking for a one-stop-shop that details the lives and rivalry of these two Caissaic giants.

Thank you very much for the review!