Book Review: The Real Paul Morphy, by Charles Hertan

Part Game Collection, Part Biography. A look at the whole of the American giant.

Introduction

Paul Morphy is one of the most important figures in the chess world, which is why so much ink has been spilled poring over his games and his tragically short career which ran for a period of just a few years from 1857 to 1859.

He’s one of the most often-recommended players whose games amateurs are told to study, and it’s easy to see why. His games contain a certain elegance and simplicity, straightforwardness and beauty, which even now is hard to match. Other players whose games are described with these terms include world champions Jose Raul Capablanca and Bobby Fischer. And in general, Morphy is considered to be the first true positional player.

Yet, this is not to say that the storied narratives about Morphy are all true, which the disproving of some Hertan is concerned about as much as he is eager to show the reader Morphy’s games, and sometimes from a new angle. In that sense, The Real Paul Morphy has a bit of a split personality. It’s a game collection. It also endeavors to give the reader a more nuanced view of the “Romantic Era” in chess (if such actually existed). In this sense it seems like a spiritual cousin to Willy Hendrik’s style of writing (indeed, Hendriks’s The Ink War and On The Origin of Good Moves are cited many times in this book). And lastly (perhaps primarily), it is an investigative biography of Morphy based on as many credible sources (including old correspondence) as Hertan appears to have been able to find.

The Two Schools

Before Hertan jumps directly into the full life story of Morphy, he gives the reader an impression of the two competing chess schools at the time: The Italian School vs the French School. This categorization is a bit more nuanced than “romantic” vs “strategic” — it goes back to the recommended ideas that old theoreticians like the Italian Giachino Greco and the Frenchman François-André Danican Philidor.

Greco, whether in reality or in constructed games, engaged in sharp piece play and wrote reams of theory, some of which has shockingly withstood the test of time today (mostly these are direct, forcing Giuoco Piano lines that bear his name such as the Greco Gambit, Greco Attack.

Philidor believed that the pieces should be placed behind the pawns instead, and that this was the basis of a sound position. This meant that Philidor, in contrast to Greco, advocated for more closed or semi-closed positions. He therefore often recommended moves such as …f5 prior to placing a knight on f6. His name also bears the name of a particular endgame and the move 2…d6 after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3, though his doozy 3.d4 f5?! leaves much to be desired on the opening theory front; his ideas were much more sensible in non-open games.

While drawing a sharp distinction in these styles nowadays doesn’t make sense (for instance, the “Italian School” opening Italian Game’s mainline variation known as the Giuoco Pianissimo leads to many positions nigh-, if not actually indistinguishable from the “French School” Closed Ruy Lopez), it does help to explain the choices of certain players 150 years ago. And Hertan begins not by showing us Morphy’s games, but his forbears La Bourdonnais, Staunton and Anderssen.

Morphy’s predecessors

La Bourdonnais was a “French school” player who employed the Ruy Lopez and French and Sicilian Defense. The Englishman Staunton also played the Sicilian, but is well-known for his first attempts at popularizing what we now call the “English Opening”. His slow and strategic buildups earn the ire of many analysts now, but his idea was quite visionary at the time and nowadays certain pawn structures could rightfully bear his name.

Hertan says of Staunton: “If positional play truly has a ‘father’, surely it was Howard Staunton, not Wilhelm Steinitz, whose arcane style was more often ‘strategic’ than ‘positional’ to modern sensibilities.” He also includes a few games I found extremely instructive, including a pair of games to show Staunton at his worst (tactically) and at his best (strategically) against Cochrane; and an incredible endgame against Saint-Amant.

Lastly, Anderssen is often billed as a romantic-player through and through, a la Italian School. But he was also a French School adherent. His 1.a3 transposes to something anticipatory of a more modern English opening (since on move 2.c4 he has actually transposed to a Sicilian Defense with colors reversed); and his move 5.d3 in the Ruy Lopez still carries water. These were closed positions being played wonderfully by the same guy who produced the Immortal and Evergreen games. I had already seen Hendriks decry the continual shoehorning of Anderssen’s reputation as an inveterate swashbuckler, but revisiting some of his games even here before the 1860s helps me see the proof in the pudding: Anderssen was a very strong strategic player and, in this sense, much ahead of his time.

After this, we get a surprisingly detailed biographical treatment of Morphy’s immediate family, especially his father and his uncle, both of whom were strong players in their day. The amount of information that Hertan was able to source was somewhat shocking, but helps to tie a long-running narrative thread from the younger years of Paul’s life to his increasingly sad mental state as he aged.

The Biography

Morphy was a Louisianan who lived in the antebellum South, who held a number of views that set him apart from his own countryman and in some cases his own family pre- and post- the American Civil War; the effects of which do not show up on the chessboard, but does give a lot of context to the man whose moniker is the “Pride and Sorrow of Chess”. Hertan takes a reserved approach, relying on his experience and knowledge as a professional psychotherapist to make some educated inferences of Morphy’s mental health issues. At the same time, he helpfully dismantles or refutes prior psychological analysis which came down to outdated and disproven ideas or in some cases completely unfounded rumors and gossip.

Another narrative thread that snakes its way through the pages is the unfortunate story of Staunton’s refusal to play Morphy. Though Hertan is careful not to unnecessarily villainize the Englishman and to rehabilitate his reputation somewhat, the whole plot of Morphy and Staunton’s non-existent match does have a bad guy, and Hertan is sure to find him out for the reader.

In fact, if like me you’re not aware of the facts of Morphy’s life and would want to find out, The Real Paul Morphy is a great way to get an updated distilled version of his full adventure. The bibliography here for both quoted analysis and Morphy’s history is rather deep, from the analytical stalwart Kasparov to Morphy’s very own contemporaries; and it comes across as a commendable effort devoid of suspiciously convenient plot points, though Hertan allows some disclaimed and honest conjecture at certain points.

The Games

But I had other reasons to pick up and read The Real Paul Morphy. My only other experience reading about him was Valeri Beim’s Paul Morphy: A Modern Perspective, which was not exactly the most positive, probably because it felt too critical of Morphy’s play, and wasn’t quite a “Best Games” collection. It was instructive, but perhaps woodenly so.

The Real Paul Morphy also isn’t quite a “Best Games” collection either, but that is in part because it includes a lot of mismatch games between Paul and a number of club players, including blindfold simuls and odds games. This isn’t a fault at all, by the way, rather a strength: While Morphy’s short career is lamentable for all of the felt lost potential, it makes for convenient and well-paced story-telling as he moves on to the next tournament, match, or simul. And since The Real Paul Morphy is a biography first, this gives Hertan every excuse to include a lot of games without concern about paring things down to an arbitrary number. All of this means we get a whopping 137 games, most of which belong to Morphy, but also some played by the aforementioned others earlier in this review.

As far as the analysis goes, Hertan usually favors what I like to call a more “historical survey” approach a la Hendriks. This is appropriate, because one of the typical remarks about Morphy was his ability to improve over a short period of time — it’s best to see how exactly we can come to that conclusion. Yet Hertan goes further: He shows that Morphy’s repertoire, unfairly derided as “limited”, was actually in a constant process of strengthening. Hertan shows Morphy as a competent probable reader of published analysis and games who came up with improvements and novelties, even uncorking surprising preparation in his matches. Also important to the plot is Morphy growing in favor of French School ideas such as the Ruy Lopez and grinding down players in closed positions and endgames. Most interesting to me is Morphy’s very successful adoption of the Dutch Defense. Hertan is quick to note that Morphy’s play appears very modern in such positions.

Since Morphy’s most famous games have already all been analyzed to death, Hertan dedicates relatively little ink to them comparatively, and instead focuses on more interesting elements that have been ignored or quoted uncritically: the most frequent of which were the endgames. I found this chosen route surprisingly helpful and Hertan’s analysis is straight to the point as he overturns, in some cases, over a century-old analysis (for instance, Lowenthal and Maroczy have their names dropped many times). Of course, whenever the narrative thread needs tugging along, Hertan points out probable reasons why Morphy or his opponents may have chosen one idea over another.

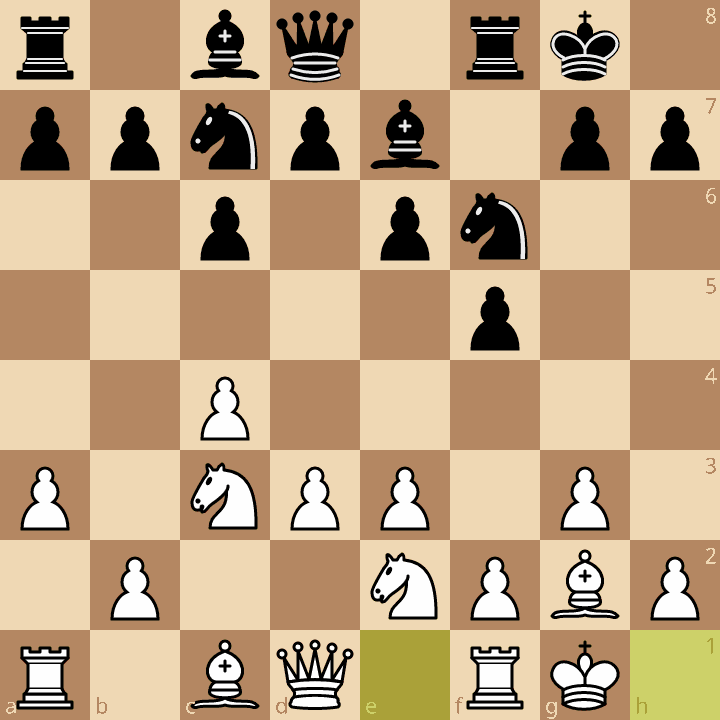

One example is in the analysis of a game against Lichtenhein:

Hertan here is relying on Fritz 18’s ideas to uncover a potential idea that he thinks Morphy may have had in mind here: 15…O-O! The point is that after 16.Qxe5 Rfe8, White must give up the queen or be mated (the idea is 17…Qxf1+!! 18.Kxf1 Bh3+ 19.Kg1 Re1# — the classic Judit Polgar tactic).

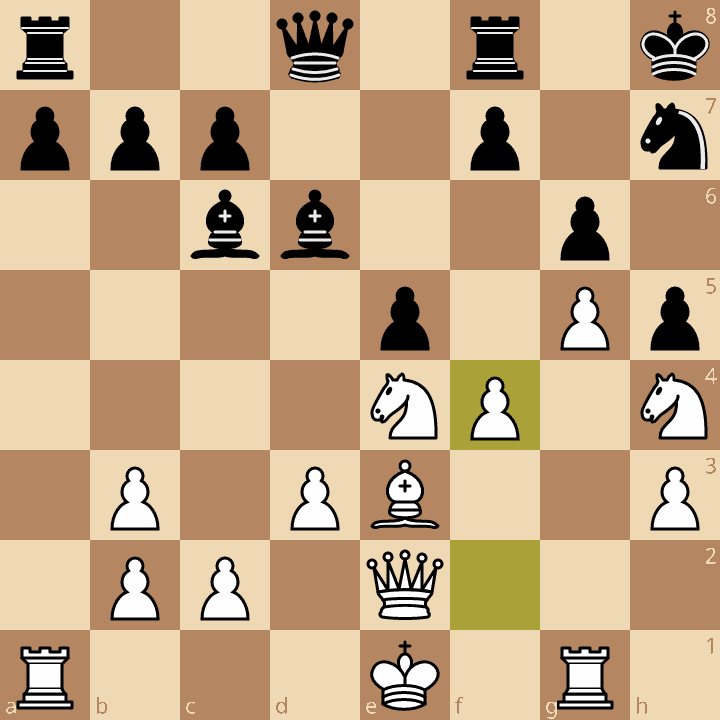

In the very next game with the colors swapped, Morphy plays for an attack against Lichtenhein.

This game features analysis on Black’s 22nd move where Hertan takes the time to explain the depth of Morphy’s prior attacking move 18.f4!? and shows that while the critics were objectively correct that Morphy’s attack was unsound, it’s the kind of move someone like Tal would make, because Black’s line to a better position is razor thin — two out of “fifty” possible variations. Hertan’s advice is cogent: Don’t be too critical of this, because it was a great practical choice. But he also becomes derisive when he scare quotes their label as “experts”.

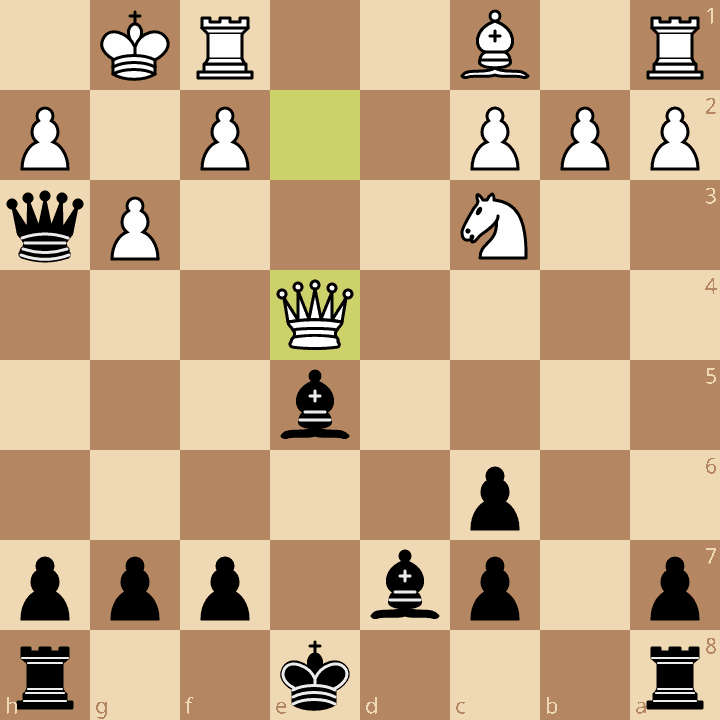

To that point, I do think sometimes Hertan goes a little overboard. In the notes to Thompson - Morphy, American Chess Congress Game 3, Hertan quips “such games make it hard to fathom how some dispute that Morphy was ahead of his time positionally.” I found this a rather vague claim — and one I’m unsure anyone has actually ever made. But Hertan goes further and takes aim at Bobby Fischer and Fred Reinfeld’s conclusion that “closed positions were Morphy’s ‘only weakness’”, arguing to the contrary by example. By the end of the book however, I think Hertan convinces me here. This particular critique of Morphy never sat easily with me when I read all about it in Beim’s book; Hertan shows that it was quite overblown.

Hertan is also not above critiquing Morphy’s play himself, but he does this with a light hand. One enduring observation he makes is Morphy’s earlier predilection for “coffeehouse play”, which could land him into trouble in the middlegame. Another thing he points out is that Morphy lacked patience in some positions to play slowly, which would have led to easier wins, though this must be tossed up as a question of style.

Apart from perhaps too-eager dismissal of earlier analysis, one thing I took note of for the first print edition of The Real Paul Morphy were a slight uptick in analytical or typographical errors nearing the end of the book. In some cases, it seems that a few moves unknowingly went missing from the middle of an analysis line; in others a nonsensical move is suggested; and at least in one case, a clear win is missed in an analysis line. Thankfully none of these errors detract from the core of the games in which the analysis occurred. I felt this was just an odd quirk, perhaps from Fritz 18, or just simple human error. In any case, I’m confident New In Chess will correct these in time (I sent my findings to them before writing this review).

The most interesting thing about the book is that we get to tour the world just like Morphy does, and meet all the different characters, some more savory than others. We learn of a Morphy who was revered both on and off the board (and how he gained this reputation); we learn of his publicity manager, Frederick Edge, who was probably the worst cog complicit in the Staunton Affair; we meet people who would become long-term acquaintances and sometimes friends; we also get to see Morphy decline mentally, and to see firsthand reports of what he was like during this. But Hertan kindly doesn’t let the book end on this historical sour note; rather he lets others speak their best of the American great to remember him in the best light possible.

It has to be said that The Real Paul Morphy, unlike, say, Ding Liren’s Best Games, is much more about the history of the player and his ideas, rather than worried about what someone can learn from them. But this isn’t to say that the reader can’t learn from it; quite the contrary! Just remember that improvement isn’t the emphasis. The games are instructive, and the analysis or notes will often point out something the reader could learn from, but it’s not about finding the most didactic moments from Morphy’s game and giving them to you on a silver platter; instead, seeing Morphy play the Open Game has a good possibility of building up one’s knowledge and experience in those and similar positions. Don’t underestimate the ability of the game’s beauty to inspire your play. Even if you don’t play 1.e4 or 1…e5, Morphy’s accuracy was ahead of his time, so much so that he remains a model player for today’s student, in an era where correctness is prized over beauty.

Conclusion: The Definitive Morphy Book?

Because the subject matter isn’t about helping any particular subset of player improve, I think anybody who likes to study chess games should consider picking up this book if they want to study Morphy’s games and get a nice side dish of chess history with a whopping heap of chess culture seasoning.

Has Hertan produced the magnum opus on Paul Morphy’s life on and off the board? I’m not sure yet, but this one is very good and I happily recommend it to basically anyone.