Book Review: The Philosopher and the Housewife by Willy Hendriks

A thought-provoking critical look at the Nimzowitsch-Tarrasch debate

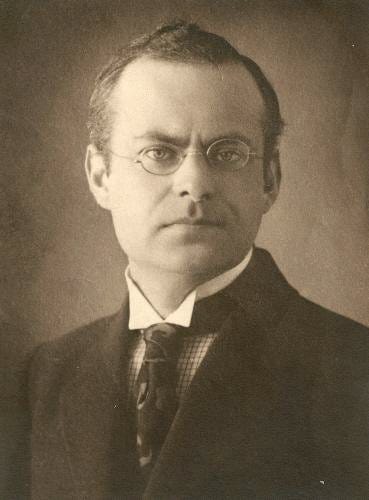

Willy Hendriks is nowadays known as the champion of heterodoxy within chess, at least when it comes to how players become stronger at the game. And so we should not be surprised to see that he takes another scrutinizing stare at the landscape of chess strategy, this time in the form of the debate between Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch. These, respectively, are The Philosopher and the Housewife.

The typical narrative of these two players is something as follows:

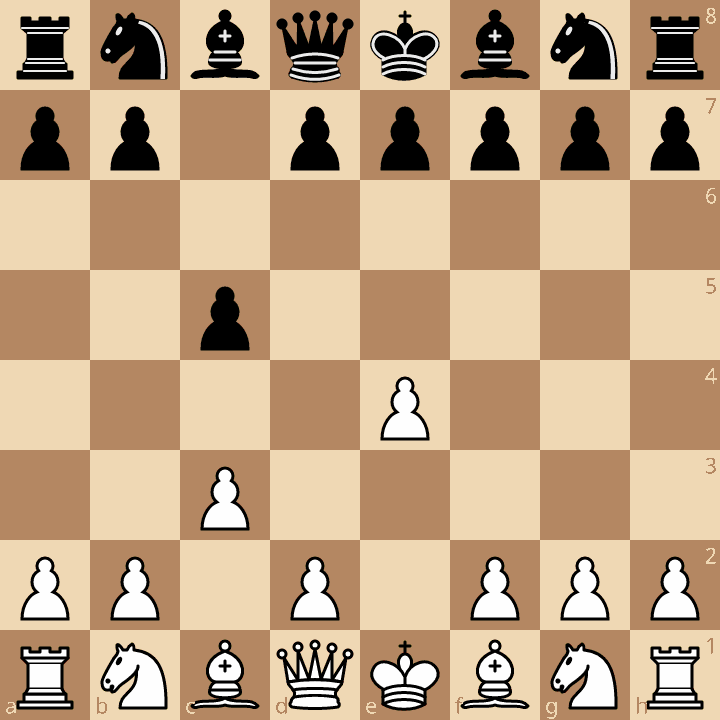

Tarrasch is the representative of a very refined form of Steinitz’z modern school of chess. He’s dogmatic and brash. He favors classical development: Knights before bishops, castle early, send a pawn into the center right away, and hold on to it as long as possible! He values openings that aggressively fight for equality, and therefore, 1.e4 e5 is almost obligatory, and we also know of his variation in the Queen’s Gambit Declined, where after 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3, Black doesn’t settle for less space and instead immediately breaks with 3…c5! Tarrasch is inflexible, and boring. He doesn’t have a deep conception of the game. But he’s generally safe to recommend to amateurs looking for advice.

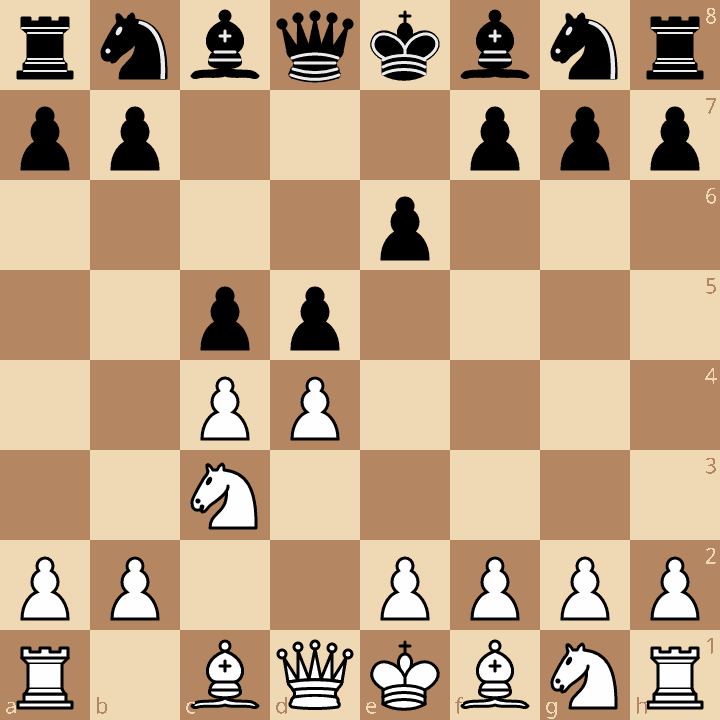

Nimzowitsch is the father of hypermodernist chess. Here’s where you break all the rules! Forget occupying the center, just hit it from afar with your pieces. Don’t maintain the pawn structure in the French — sacrifice it and put your own pieces on d4 and e5 instead! Why fight for equality when you can prove yourself superior? Nimzowitsch’s name appears on many opening variations like Tarrasch: The premier is the Nimzo-Indian Defense (1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4). Nimzowitsch is flexible and exciting. His system is the way you should think about chess. Once you’ve mastered the basics with Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch is the next step — once you’ve learned the stiff basics of the old teacher, you must move on to the new methods with the radical didact.

Of course, life and history, including chess, are rarely this simple, as Hendriks goes to painstaking lengths to show.

In one sense, The Philosopher and the Housewife seeks to challenge the dichotomy between “classical” and “hypermodern”; in fact, Hendriks doesn’t have to do this with today’s chess because that debate has more or less been settled over the board in tournament practice, with the advent of chess engines which consistently show us that almost every opening is in fact playable. Nowadays top players look less for advantages than for comfort and superior knowledge (a home turf, so to speak), and the practice of amateurs has therefore followed as new opening resources are published at a breaking pace. But it was not so clear in the early 1900s!

In their day, Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch engaged in protracted debates via chess magazines, arguing about whose style was correct; whose system of thinking was better; whose ideas were more powerful; whose strategy should triumph over the other’s. Nimzowitsch made it his life’s mission to somehow disprove Tarrasch’s theorems; Tarrasch was obliged to defend himself strongly. The end result was another bitter war of words (and sometimes actual variations over the board) over many years.

Hendriks is very aware of his advantage of being untimely born in comparison to the two main characters of his book, and therefore reserves a lot of judgement regarding the behaviors and eccentricities of both Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch. But this doesn’t leave them invulnerable to the critique of their ideas, and this is where Hendriks brings in the tritagonist: Semyon Alapin.

Alapin was never a top-rate player, though we know his name well from the variation of the Sicilian Defense 1.e4 c5 2.c3!? For Alapin, a lot of the Nimzo-Tarrasch debate was simply noise that couldn’t be settled by words but must be determined by variations. Of course, Alapin was not exactly a kind person in print either, and therefore all three characters hardly ingratiated themselves to one another and sent volley after volley of biting words after one another as they continued this debate.

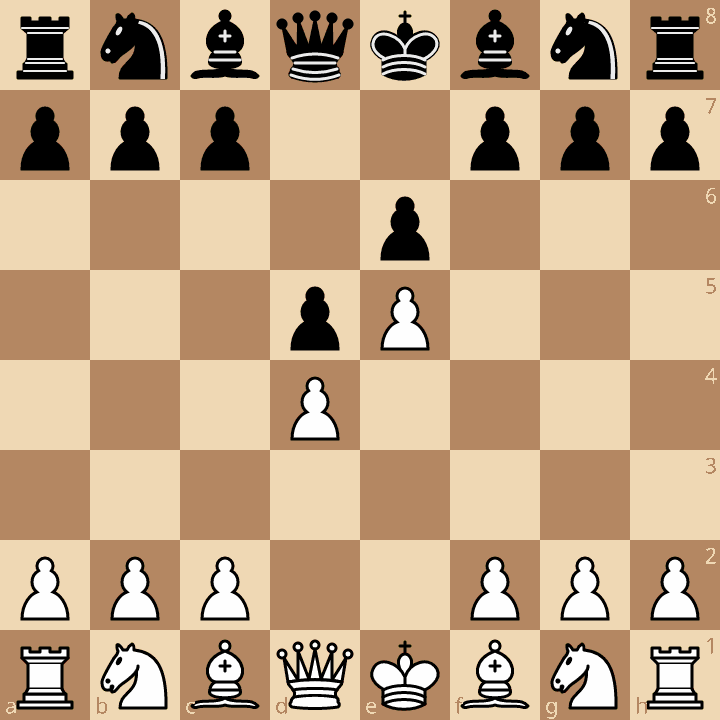

One debate that Hendriks uses to frame the opposing sides is the French Defense Advance Variation (1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.e5), which appears throughout the book.

Nowadays, this is a very common variation at the club player level, and is also often seen at the master level. But in Nimzowitsch’s day, it had fallen on hard times. The inflexibility of White’s center introduced too much weakness and Black was able to find resources easily (for instance, we can already see that with the move 3…c5 it is Black who has some initiative!). Nimzowitsch declared himself the reviver of 3.e5 after Tarrasch (as Black) announced its early death in a 1888 blowout against Louis Paulsen, and one way he did this was by uncorking an improvement of that very game as White against Tarrasch in 1912, all the way on the fifteenth move. Nimzowitsch ended up winning that game, but the debates continued for a long time, between Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch, but also with Alapin (who in this case took Tarrasch’s side, though his argument was simply that Nimzowitsch’s philosophy hadn’t led to the win, but rather that Nimzowitsch was simply gifted tactically; for Alapin, there wasn’t anything to be afraid of in the Advance French.

Alapin, of course, wasn’t as strong as either of the two main characters, and thus maybe felt a bit less credible to contemporary readers in the long run, but his critique, as Hendriks argues, has been sustained in modern chess. Hendriks is kind enough to both Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch to hold off most of his critiques until the final chapter which has one of the greatest payoffs and conclusions in chess books I’ve ever read.

Besides the arguments of Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch (and Alapin), Hendriks brings in other characters to show the general narrative of chess especially as it was forming in the 1920s and 30s, and he is quick to show how biased this narrative became among the hypermoderns. According to them, chess was becoming boring and facing a draw-death due to the Ruy Lopez and Queen’s Gambit openings. It was all technique and no aesthetic. And they (the hypermoderns) were the ones to save it.

To Hendriks, this is basic hogwash. Any perusal of games from this period shows that it was not a period of stagnation but rather of great discovery in chess. It wasn’t just Nimzowitsch, Reti, Tartakower, Breyer, and Spielmann holding the artistic weight of chess on their shoulders through deliberate heterodoxy against the established chess norms. (for the record, I agree with Hendriks, having studied hundreds of games from this period).

Be that is it may, the hypermodern critique is still in large part the established narrative. But maybe Hendriks critical journalism and historic re-appraisal is the beginning of a re-discovery of the truth that it just isn’t that simple.

Besides this, Hendriks points out the problems of narratives like Reti’s and Tartakower’s. For one, Nimzowitsch always referred to himself as a neo-romantic, and in some cases actually vehemently disagreed with the hypdermoderns with whom he was lumped. Plus, Nimzowitsch’s debate with Tarrasch was actually somewhat centered around who, exactly was the true heir of Steinitz. Nimzowitsch believed it was himself, and Tarrasch himself distanced himself from Steinitz, and you can see this both in Tarrasch’s aversion to Steinitz’s more radical ideas about the king being a fighting piece, and in Nimzowitsch’s concept of the heroic defense, which often involved deliberately allowing his king to be pushed around the board! Not only this but Hendriks takes note of the fact that it was in fact Tarrasch who was first coined as hypermodern, and this as an epithet that he was allegedly too attached to Steinitz’s table of elements. History, it turns out, is rather ironic.

Reti’s narratives face some other issues as well (and not just the latent nationalism): his all-important locus of categorization for players boils down to style. And one player who just didn’t adhere to a style that was comprehendible to Reti was Emanuel Lasker. So for Reti, the only possible explanation was that Lasker deliberately played inferior moves to outwit his opponents. And thus began Lasker’s reputation as a psychological player; Tartakower would essentialize Lasker as the pinnacle of “philosophy” in chess.

All of this is very heady and of course part and parcel of the typical chess narratives today. Yet if we could just ask Lasker, it’s very likely he would say that he was just trying to play the best move, just like the rest of us, just like he himself had actually admitted.

Lastly is the triumphant story-telling of the hypermoderns who can’t agree on who exactly is on their team. Alekhine, who incidentally debuted the Nimzo-Indian Defense before Nimzowitsch did? Capablanca? Or even the old stodgy Tarrasch who played the Alekhine Defense against Lasker in 1923?

Hendriks is really effective in showing that the real-life story is rather complicated and full of debates from players on all sides. There is often missing nuance, and sometimes downright untruths, which have unfortunately all-too-often been parroted and passed down from the ancient masters to today. In a lot of cases the authors who wrote of others wrote with a sort of feigned omniscience allowing them to peer into the minds of their contemporaries, and this oft quite uncharitably! Hendriks is quick to point this out in an effective way. I’m hoping that this healthy skeptical approach gains some more followers to challenge the status quo when it comes to how we talk about the chess of players in the past.

Besides the over-the-board debates of Nimzowitsch and Tarrasch, and the over-the-air battlefield in the chess newsletters, Hendriks takes his time to give us some biographical information about both players, and it is particularly here that Hendriks shows grace to the bitter rivals and a lot of wit in his characteristic dry humor, particularly in his slight ribbing of earlier biographers. Of note are just how many anecdotes about Nimzowitsch there are, and even how many of them are actually near to the truth. Nimzowitsch was indeed a strange person. To quote Tartakower: “He pretends to be crazy in order to drive us all crazy.” Hendriks doesn’t go quite as far as to try and give us a diagnosis of Nimzowitsch’s condition, but he does lay out the kinds of eccentricities he was known to have. It gives us some insight and maybe a little empathy for someone who most certainly felt like the misunderstood artist of his own time.

Hendriks also rehabilitates Tarrasch somewhat, not only through his OTB play, but by applying the same standard to Tarrasch as he does to Nimzowitsch. Was Tarrasch dogmatic? Nimzowitsch wasn’t any less. Was Tarrasch actually that inflexible? We see Tarrasch engaging in different ideas quite outside his own reputation plenty of times, actually. In some of the games shown, Tarrasch seems to play in a much more hypermodern style vs Nimzowitsch who takes on the classical ideals. Besides this, while Tarrasch could indeed come off as arrogant, Nimzowitsch shows no false humility himself. Of course, neither players appear to have much self-awareness on this front, as Hendriks wryly notes.

When it comes to the final chapters, Hendriks begins to make some concluding remarks and assessments about both players and their respective “movements”, and then finally proceeds to the present era and the relevance of the infamous debate between the Neo-romantic Nimzowitsch and the Classicist Tarrasch. Here is where the debate on the Advance French comes up again, and Hendriks takes a side, perhaps unsurprisingly with the ‘Variantenkünstler’ Alapin. Nimzowitsch won the battle of words. Tarrasch’s assessments of many openings which he debated with Nimzowitsch (particularly the Steinitz variation of the Ruy Lopez, and the Hanham Defense) are confirmed by engines. But philosophically, Alapin won the war.

Alapin’s views are shockingly modern for our taste, in that what matters isn’t the philosophy or how you can explain the position with words — what matters is knowledge of the variations. For Hendriks, comprehension of a position is preceded by and comprised of the competence in playing it. In other words, experience playing a position leads to practical knowledge; rather than learning by reading, one needs to learn by playing. At the extreme opposite end of the spectrum, Tarrasch would instruct his students to delay playing at all until one had perfectly understood the opening phase of their game. This is, as many an unfortunate new tournament player has learned, not only impractical but basically plain wrong. How you express the idea of the opening in words or mere memorization doesn’t matter. What matters is the variations you know and can generate effortlessly from that knowledge. Obviously modern chess engines have shown this to be true in a certain sense already. But it’s also true of human chess players. Reading a book on any opening will not make you an expert (as many of us can well-attest) — you must gain knowledge by playing it. Players become strong by increasing their competence, which grows their comprehension. This stunning line encapsulates Hendriks’s point:

When you look at a position, you see (recognize) what you already know. Therefore, when Tarrasch looks at that French bishop on c8, he sees something else than the beginner. The latter sees a total unknown, while to Tarrasch this bishop is as familiar as his closest relative. There is a world of difference between what Tarrasch sees and what the beginner sees when he looks at that bishop on c8, and that is only one element in a complex position. The idea that you can bridge that immense difference with a few well-chosen words – that is the trainer’s fallacy.

Hendriks, Willy. The Philosopher And The Housewife: Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch and the Evolution of Chess (p. 649). (Function). Kindle Edition.

And shortly after that, he unleashes this banger:

Alapin noted that this struggle cannot be decided with principles expressed in words, but only with variations. To this, I would add the Darwinian notion that understanding does not precede variations but is the result of them. Understanding a variation consists of all those variations that you can add to it in less than no time. This is why it is such a good idea to study openings. The more different openings you master, the broader your understanding of chess will be. Because that understanding does not exist in essences, but in an irreducible multiplicity.

Hendriks, Willy. The Philosopher And The Housewife: Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch and the Evolution of Chess (p. 659). (Function). Kindle Edition.

From-the-ground-up is not a common approach to chess strategy didactics, which have commonly chosen the top-down approach. Nimzowitsch’s System. Silman’s imbalances. We commonly discuss opening principles, and nearly-as-commonly are confronted with all the exceptions (in other words: variations). But in the end, the way one actually gets better is comprised of the experience gained by play. The words we use to describe our play always come after. Per Alapin, variations will always triumph over words. In John Watson’s words: “The move is the idea”.

The Philosopher and the Housewife is entertaining, informative, provocative and laughter-inducing. For those who enjoy a critical look at chess history, it’s a no-brainer. For those interested in improvement advice, the payoff for reading with patience is surely worth it — read the whole from front to back, and play through each game fragment, and Hendrik’s advice begins not only to look cogent but possibly more correct than ever. I know Hendriks is the skeptic, but you can call me a believer.