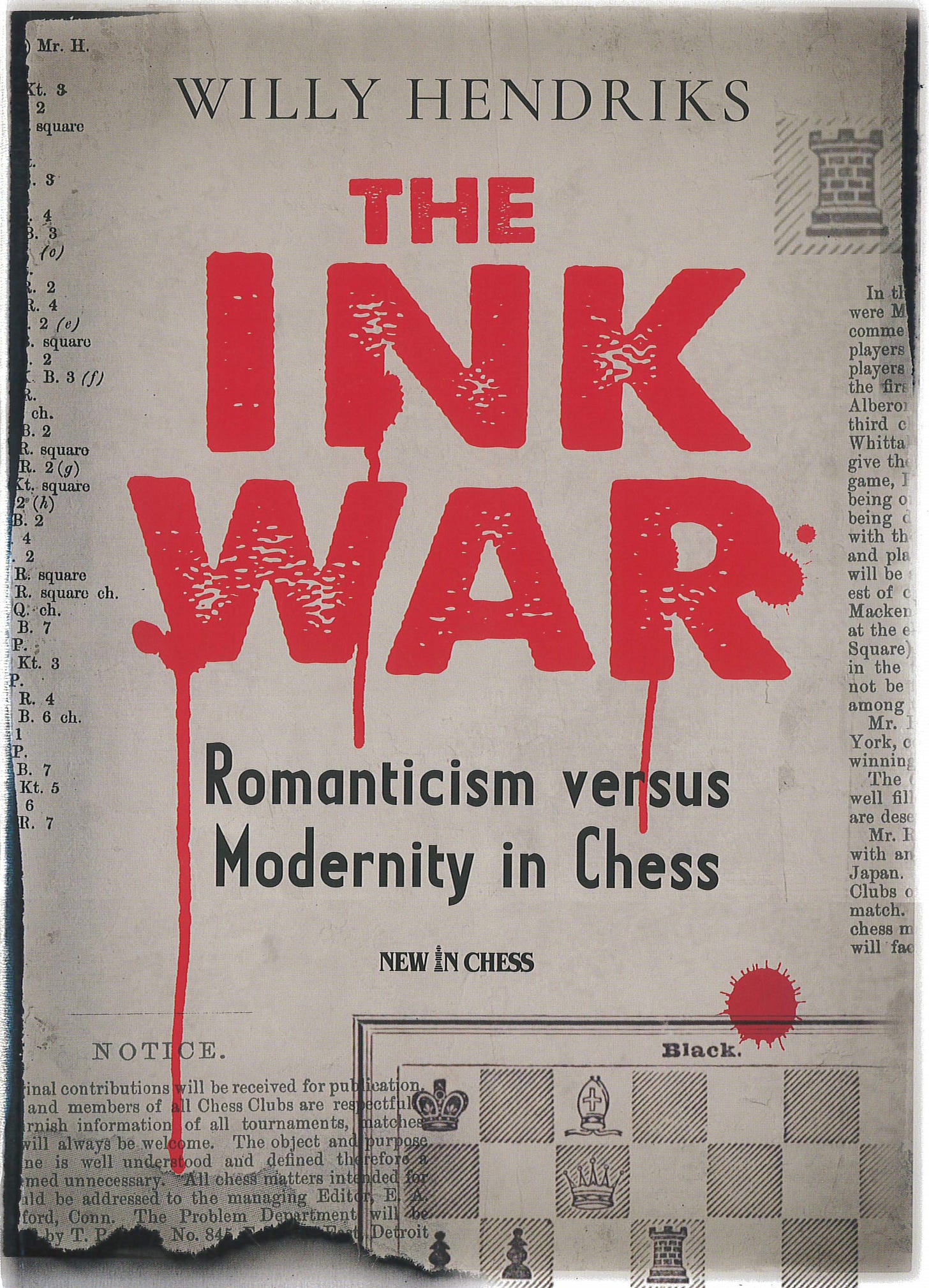

Book Review: The Ink War, by IM Willy Hendriks

Fascinating look into chess history and the first official World Chess Championship

I wrote this review originally on Goodreads and Amazon.

"Romantic chess" and "modern chess" are two phrases that one familiarizes themselves with once they begin to wade into the waters of chess culture and history. The usual distinction between these two "schools" of chess is located in the style of play that chess players engaged in. Stereotypically, romantic chess is known for swashbuckling attacks and sacrificial combinations, the disregard of one's own king safety, ever in search of the next checkmate or tactic. Modern chess, in its infancy, was derided as scientific, cowardly, and -- perhaps worst of all -- boring.

It's relatively well-known that Wilhem Steinitz became a "defensive" player as he unveiled what he described as the new school of chess some time in the 1870s, though his contemporaries described him as a thief or pickpocket who would steal a pawn and waste you away by a thin margin in the ending. It's also common knowledge that Steinitz was the first "official" World Chess Champion owing to his victory over Johannes Zukertort in 1886, a battle that lasted a bit over two months and twenty games, from New York to Saint Louis to New Orleans.

The normal way the story has been told even up to this day is that Steinitz spelled the death-knell of romantic chess by defeating Zukertort. Zukertort is often held up as (for his day) a merely very strong combinational player who lacked respect, let alone ability, for the strategic aspects of the game that Steinitz had discovered.

The author of this book, Willy Hendriks, begs to differ. Historically, the lines are obviously too cleanly cut, the differences overly exaggerated, the biographical statements too rosy or slung with mud, between Steinitz and his contemporaries; and Hendriks uses Steinitz's main rival up until the first World Championship match, Zukertort, to show that Steinitz didn't have a monopoly on the new "Modern" school of chess. Hendriks sets the stage from the beginning. The protagonist of this book is Johannes Zukertort.

Much of this sounds esoteric if you lack chess culture, because it's the sort of thing I expect only a serious chess enthusiast would probably enjoy, so a quick profile about me: 32 years old, started playing chess six and a half years ago, I am Class-B USCF-rated player (rated 1693 at the time of this review). I'm onto my second year of studying the games of masters, and while I visited Steinitz a year ago, once I saw The Ink War was published, I wanted to give this era of chess another go.

This book is not like the game collections I've read through. Those consist mostly of collections of the best games from a player's life, with some analysis and annotation by another player, and the main purpose of these is to teach you how stronger players think and play.

This book is decidedly different. Hendriks wants to teach you, not how to play chess, but how chess was beginning to be played especially in the wake of Paul Morphy's sorrowful departure from the game of kings. Hendriks also wants to present the players through the eyes of their contemporaries, and especially in the case of Steinitz, who is cast as an anti-hero throughout the story, through his very own eyes.

The 1886 World Chess Championship looms on the horizon from the very first pages of the book, but Hendriks takes his time setting up the entire plot; things begin almost as a conspiracy, and we are introduced to many famous chess players from the 1800s as the story continues. Morphy's shadow pervades every corner of the career and quest for legitimacy by Zukertort and Steinitz, even as they make pains to defeat the best players in Europe. We meet such characters as Adolf Anderssen, Louis Paulsen, Henry Bird, Samuel Loyd, Mikhail Chigorin, and Siegbert Tarrasch; all of these were strong masters, many of whom had played against Morphy themselves, and some who receive some of the spotlight throughout the story in wins and/or losses against our two main characters. Most notably, if there's a deuteragonist, it's Joseph Blackburne, a very strong player himself, who is not quite up to the level of Zukertort -- a lot of his games are shown in this book and it's a nice treat to watch him and Zukey go at it in their fateful match. In the final chapters we are at last introduced to Emanuel Lasker, the second official World Chess Champion after Steinitz.

For the most part, the book goes in chronological order. Through the use of profuse game fragments, Hendriks weaves the 14-year-old plot together both over the board and away from it. This isn't really a game collection, though it does contain the full score of the 1886 World Chess Championship with sparse notes from the author -- and this is for the best given the historical nature of the book. Hendriks does provide a number of exercises for most chapters which contain these games or fragments. Most of them are tactical, though some simply ask for an evaluation, while others are decided strategical in nature -- good practice for any player rated 1400 and up. I imagine most experts would find these a breeze however. Some are more challenging than others; they're presented in the order that the games they come from are distributed in the chapters. The book isn't about adult improvement, but I think Hendriks has a keen eye for his audience, so if you're like me, you will enjoy the puzzles -- it can't make you worse for the game, and you may find yourself pleasantly or unpleasantly surprised at your understanding of the positions compared to those of the old masters!

The title of the book, "The Ink War", refers to the rather protracted disputes that Steinitz and Zukertort would engage in through their respective chess newsletters or magazines, and Hendriks is careful to give that context, since in a lot of way, the Steinitz-Zukertort rivalry would spill off the chessboard onto the papers, and subsequently there would be new progress towards what would eventually become the first World Chess Championship. If anything, we're getting a rather interesting glance into the characters behind the famous names of the 1800s chess scene. Hendriks lends some sympathy to the old masters: their livelihood was staked on their reputations, and given that both protagonist and antagonist come from persecuted backgrounds as poor Jewish immigrants in Europe, it's no small deal to be accused of anything that could detract from that livelihood. Whatever infamous disputes we have today between players like Carlsen and Niemann, the stakes were much higher and existential in Steinitz's and Zukertort's day.

The actual Ink War plays a very interesting role in the book. We get to know a bit more about the relationship between Steinitz and his peers (he was disliked, and in his efforts to vindicate himself made more enemies in what often became an increasingly vicious cycle), and especially between Steinitz and Zukertort, who began as friendly rivals but became fierce competitors in editorials and on the 64 squares. There are some dryly humorous moments which Hendriks points out, and they certainly elicited a chuckle out of me; YMMV. Hendriks also gives us some insights into the state of opening theory, and also the state of just who exactly had the right to share any opening theory (according to Steinitz anyway). Such gatekeeping is still known in the chess world today, actually!

It's important to remember the thesis: The lines of romantic chess and modern chess were already blurring by the time Steinitz was making hawkish claims about his new school. Zukertort was one such example, but we also see Hendriks highlighting Adolf Anderssen. Anderssen's games are some of the most famous in all of chess -- no appreciator of chess can look at the Immortal Game (a prime example of romantic chess) and walk away without at least a small smile on their face the first time they see it, but Hendriks takes pains to show that Anderssen was no anti-strategical tactician, but was, like some other strong players of the time, a respectable positional player. This refusal to sharply divide romantic and modern chess makes a strong impression when you consider that Hendriks uses well over a hundred fragments to prove his points.

With this fresh on our mind the entire read through, Hendriks takes us through many of the tournaments where either Steinitz or Zukertort made their lasting marks, to show why both players had an equal claim to the unofficial title of World Champion; and sets everything up for the final stage: the 1886 World Chess Championship. Hendriks respectfully cuts our two men a lot of slack, refusing to engage in the chronological snobbery of the latest chess engines, but still makes some very interesting remarks about the match. For one, for all of the typical framing of new school vs old, Steinitz vs Zukertort, isn't it interesting that Steinitz plays nothing but the King's Pawn Opening? Zukertort was one of the first to experiment with the Queen's Pawn -- and he stuck to it for the majority of this match. Meanwhile, Zukertort was lambasted as a hamfisted attacker whose accuracy could only truly be found in the short-term combinations, not the long-term strategical play that Steinitz was putting forward -- but really he was the one discovering that you could play on the queenside in the first place -- romantic chess players barely knew that half of the board existed. Also, as the eternal subject of stereotypical preaching about the importance of central control before launching an attack, Steinitz himself didn't always follow his own rules, and launched objectively unjustified attacks which still succeeded as Zukertort's resistance over the last two months of competition continued to wane. In the end Steinitz is proven the victor, the positive history is written about him, and Zukertort's career ends ignominiously. It's clear that Steinitz was the better competitor, and the stronger analyst, but Zukertort's demise is still sad to witness -- and not all too unfamiliar, if you pay attention to other chess world championships -- one side gains momentum and finally outlasts the other, who collapses, exhausted, beaten and bloody on the cold hard checker-tiled floor.

The end of the Ink War is, of course, an anti-climax. Steinitz and Zukertort never meet again, and for many historiographers that's the end of the story. Hendriks recalls a few blunders made by Zukey after the match with Steinitz, but, not willing to hang his protagonist out to dry in the winds of schadenfreude and deteriorating health, leaves it at that. Zukertort dies in 1888, two years after the championship match. It's what happens after Zukertort dies that really cements Steinitz as the antagonist of the Ink War, because Steinitz continues to fight even after his opponent is unable to resist further -- declaring the victory of his "new"-school over "Zukertort's" old-school ways. Hendriks also shows how the Lasker wasn't able to appreciate Zukertort for what he was at his best: an amalgamation of romantic and modern chess -- it's hard to disagree once you've read the whole book.

I would recommend this book to almost any serious chess enjoyer who would like to learn a little history about the chess world championship -- you're likely to have some fun whether it is with the prose or any of the games or game fragments which are analyzed or presented (my recommendation is to keep a board at your side, or a lichess study); or reading boisterous segments from the various players and chess journalists writings. Just come with a bit of an open mind. Hendriks is known for being a bit of an iconoclast when it comes to chess improvement, but it's hard to conclude he's overstating his case here.

5/5

This is a superb review, it seems you've really captured the essence of the work. I've learned quite a few things! The only fault I can find with it, is I may not need to read the book itself. Terrific stuff, thanks.