Book Review: The Amateur's Mind, by IM Jeremy Silman

A controversial classic that has grown on me over time.

Almost everyone in chess knows the name of the recently late Jeremy Silman, and for good reason. He was one of the most beloved and prolific authors in modern chess, and for many a strong player, the de facto coach based on books like this one and the even more rigorous How To Reassess Your Chess. This book needs almost no introduction, but I am writing a review because it wasn’t until the third attempt at reading it that I was able to complete it, and part of that is because I think I was finally at the level where the writing was starting to make sense.

So this is a review, but it is more so an attempt to convince the skeptics that you really should try this book a second or third time to see if it doesn’t hit a little different since you became a bit stronger. I think this book is fully deserving of the title of “classic”. And I think that specifically it makes a lot of sense for the ambitious club player (I think that the Amateur’s Mind is mostly intended for players between, say, 1200 and 1800 on the USCF rating scale) to pick up, because this book is a treasure trove of good practical advice for over the board games, in addition to the good ideas that any player, online or IRL, can employ in their games.

First, a bunch of quotes, because this book, like any good thing in chess, speaks for itself.

I highlighted a lot of quotes from this book to illustrate that, but I’ll share relatively few. If this whets your appetite for studying chess, buy this book and read it.

Page 27: “He should have decided on capturing the Knight before he played Bg5. Don't stick your Bishops on b5 or g5 and act shocked if the opponent "tickles" it with ...a6 or ...h6. Only play a Bishop to those squares if the exchange is good for you or if the opponent can't break the pin.”

Page 37: “Don't accept that you have made an error without a fight! An objective look at the position may show that you have a good reply.”

Page 53: “Remember: only attack something if the move improves your position even after he defends the attacked object…. The amateur often thinks that a move with a threat is something to covet, when in reality a simple threat is usually easy to parry. The real quest is to find a square where the piece is happy, active, and secure. Avoid squares where it makes a one move threat and then gets chased away.”

Page 67: “A spatial plus is a permanent, long-term advantage. You don't have to be in any hurry to utilize it. Take your time and let the opponent stew in his own juices.”

Page 69: “Fearing every possible threat that the opponent can throw at you turns you into a timid player who reacts to ghosts. Avoid this label and make sure that every move you make does something positive!… Every move you make should have a positive base and be geared to increasing the advantages that you already possess.”

Page 107: “If you ask an amateur player what he thinks of when you say hanging, doubled, backward, or isolated pawns, the most likely response will be "a weakness." Unfortunately, most amateurs don't really know how to go after pawn weaknesses, much preferring the thrill of a King-hunt. The other side of the story follows the same pattern. If the amateur gets these so called weaknesses, he usually panics because he is not aware of the dynamic potential inherent in all these structures. The simple truth is, it's impossible to label anything in chess as always being weak.”

(There’s a striking example in the book on pages 127-129 where he shows that, actually, tripled pawns can be good, in order to further illustrate this point.)

Page 139 (on not panicking after almost committing a blunder): “Everyone has been unpleasantly surprised or has had the experience of noticing usually at the last moment- -that their intended move is bad."

If this happens, you must not make any hasty decisions. Instead, forget about the game and take a few moments to calm yourself down. Once this is done, you can reassess the situation and avoid making a decision based solely on emotion.”

Page 140: “All chess players should get rid of words like maybe and somehow. Clarify what's going on to the best of your ability; perhaps you won't get it right but at least you will be creating some good habits.”

Page 141: “I don't mind incorrect analysis or incorrect thinking--people can only perform at whatever level they have reached. Laziness, though, is a preventable disease that makes improvement impossible.”

Page 143: “Don't allow surprise or depression to influence your moves. If something unexpected or bad happens, you must sit on your hands until you regain your equilibrium. When this is done, reassess the situation as if the game were starting over again and calmly figure out what the position needs.”

Page 147: “When you win material you may find your pieces are off balance and without purpose.

That is because they have fulfilled their mission and now need a new goal. If they are off balance, don't keep lashing out. Instead, bring your pieces back together, make everything tight and safe, and then prepare a new plan based on your material edge. Remember: extra material gives you a long-term advantage. You don't have to be in a rush to use it.”

Page 174: “Though most gambits don't really work in the professional ranks (White is happy to try and make use of his extra move), amateurs can learn a lot from initiative-seeking pawn sacrifices.

Ultimately, though, you have to be able to do both: mastering positional (static) ideas on one hand and making use of dynamic strategies on the other.”

Page 182: “When you are trying to make use of a dynamic edge you should take your time and look long and hard for a knockout. This doesn't mean that you are playing only for mate. Far from it! A superior endgame, the win of a pawn, a huge positional plus; all of these things are good value for your dynamic dollar.”

Page 188: “Knowing your own plan isn't enough, you also have to know what your opponent intends to do!”

Page 202: “Don't play with fear in your heart. If you play with courage, the worst thing that can happen to you is a loss. Since we will all lose many games in our lifetime, we might as well go down with honor and make every game as instructive as possible. Playing passively and getting routed is no fun at all and teaches you nothing.”

Page 221: “The basic rules we learned when we started out are good guidelines but must be broken often. Don't fall in love with these concepts and become blind to the reality of any given situation.”

Page 263: “You can't let every little possibility by the enemy cause you to panic. If you see something that worries you, look at it closely and make sure that it's worth stopping -- you may find that you are often preventing a bad move that the opponent never intended to play!”

Page 264: “An insistence that every move you make creates some sort of gain will get you far in chess.”

Page 276: “A person that does nothing but attacks the enemy King will end up a loser most of the time. Balance, and a willingness to do whatever is called for, is the key to success in chess.”

Page 282: “Try to notice when the transition between thinking of your own ideas and reacting to the opponent takes place.”

Page 288: “Insist on making good things happen for your position. If it takes you a lot of time to find these ideas, then consider this time well-spent.”

Page 310: “Treat everyone you play with a touch of contempt! There is nothing a higher rated player hates to see more than an opponent who refuses to be respectful to a superior.”

OK, we’ve got that out of the way. And there’s still so much more. I’m just hoping to have already convinced you before having to give my own thoughts about it.

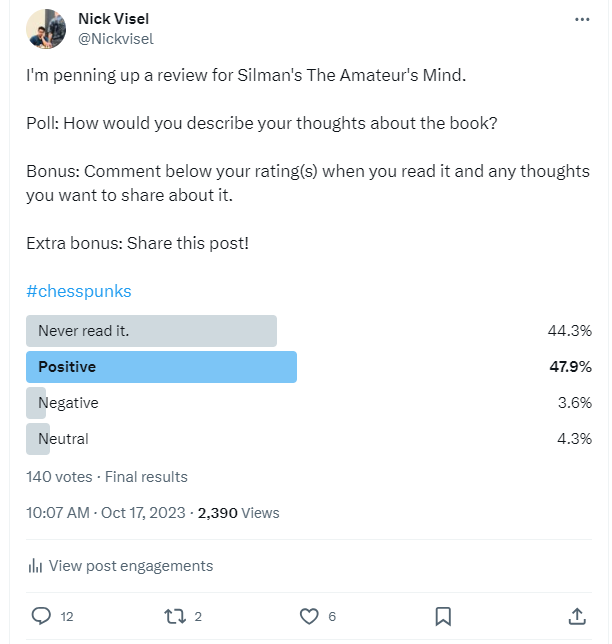

What others think about The Amateur’s Mind

I ran a poll on Twitter to get some feedback about The Amateur’s Mind. One reason is that I have heard over the years that it is considered “controversial”, or that many think it’s not really good. However, I wanted to see what #chesspunks community and those adjacent to it thought of it. I was somewhat surprised by the results:

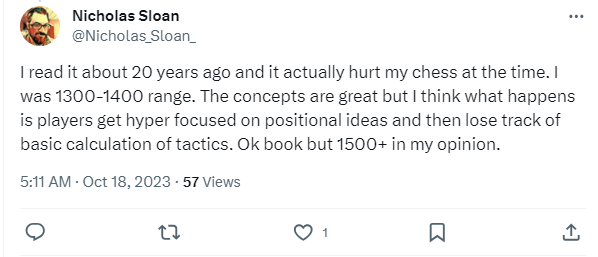

More people than not had read it. Of those who read it, almost all of them had positive thoughts about the book, not negative. There were a few negative responses, but by and large, it simply wasn’t the controversy (based on this small biased sample size) that people made it out to be. Heck, even the non-positive responses were qualified and nuanced:

These critiques are, for the most part, rather tepid for a book of this stature!

The positive thoughts, also sometimes qualified and nuanced, outweigh the negatives for sure:

My own thoughts about the book

I bought it maybe four years ago and tried to read through it a few times, but could never get past the material which was overwhelming and new to me. The concept of imbalances was difficult to understand, and I wasn’t entirely sure I should filter my chess thinking through that rubric. In fact, I still have some reservations. But what matters is that even if you don’t 100% wholesale buy into the Silman Imbalances thinking process, the advice is still generally sound, and the examples themselves are excellent.

If you don’t know what an “imbalance” is, Silman lists the following (parentheses is me trying to briefly explain):

Minor pieces (e.g. knights and bishops — who has what?)

Pawn structure (broadly, dealing with doubled, isolated, backwards, passed pawns etc.)

Space (or territory — how many squares you control, often defined by the squares behind your pawns)

Material (who has the more valuable pieces?)

Files and squares (files, ranks, and diagonals, and even individual squares on which your pieces may reside or control)

Development (who has more pieces out, who is castled? etc.)

Initiative (who is the one making the threats?)

You get a chapter with many examples of how to deal with each of these subjects, plus he tackles the idea of psychology and trends in thinking and how that can affect one’s ability to find the right plan. Combining all of these together helps give you an idea of what you should be doing in your game especially when a tactical opportunity hasn’t presented itself at the present moment.

If it’s unclear from the title, Silman’s idea in this book is to take positions which have some positional advantage based on an imbalance., often from master play, and present them to various students (e.g. the amateurs) of different levels, ask them to evaluate the positions and give their thoughts about them, come up with moves, and play against him. This is the core aspect of the book, and it’s extremely instructive to see both the players’ thoughts, and Silman’s thoughts about their thoughts. I feel like Silman, more than most authors, has his finger on the pulse of the average club-level player (even up to expert), and is therefore able to give very plausible answers to the sort of mistakes some of these players make. Silman often comes off a bit harsh at first in his critiques, but he also knows when to compliment his students — thinking above your normal level is hard work, and he recognizes that, which I think is important to motivate people to become stronger.

At the end of the reading section, you’re then gifted a test chapter where you can see if you can apply the things you learned. Don’t worry if you don’t score well on this initially — that’s part of the point! You want to know where your weaknesses are and then work on those until you gain more understanding and can convert that into skill. This is a huge cherry on top of the instructional content in the books, because Silman doesn’t just give a terse answer in the form of some myriad variations — he generously and fully annotates the answer and ensuing moves so that there is no possible way you won’t come out of it learning something, even if you got the answer correctly.

There’s probably not much I can say about this book that others haven’t already said, since it’s been out for so long. I’m mostly writing this as a recent “convert” to someone who does actually like this book, because it took me a long time to get there.

Buy it, but…

I do recommend it with some caveats:

This book, like How To Reassess Your Chess, is one of those “jack of all trades, master of none” types. There are certainly better books on any of the subjects contained in this book, especially if they are dedicated to the study of that particular topic. Silman clearly tried to make this as digestible as possible for the widest swath of intermediate-skilled players he could.

There are other books that basically teach same things, but in a more accessible, less testing way. For instance (and I agree with him), Neal Bruce suggests both “Simple Chess” by Michael Stean and Winning Chess Strategies by Yasser Seirawan as “more useful” choices:

The imbalances system is not meant to replace your entire thought process. This is less of a caveat about the book, and more a warning not to try to make it fill holes it wasn’t meant to patch.

Depending on your skill level, this book might not be necessary, since you’re already at the level where How To Reassess Your Chess makes more sense. Silman also thought that is the better book, but I’m not actually sure I agree, based on my experience with both books. However, I think that the Amateur’s Mind is mostly intended for players between, say, 1200 and 1800 on the USCF rating scale.

The analysis may not always hold up. This is true of virtually all chess books, but especially those done before the era of AlphaZero. That’s just the way it goes. But even if the analysis is not correct, the ideas behind the moves are still worth seeking to understand, and this kind of thinking may be very helpful in your journey to become a stronger player.

This book has its detractors, and for reasons I consider legitimate. I’ve even heard on one podcast episode that the reader basically felt afterwards that the concept of making a plan according to the imbalances and thinking about positions with words was “bullshit”. He found Willy Hendrik’s ideas (e.g. “Move First, Think Later”) much more inspiring. And perhaps that is a strong reminder that Silman’s style won’t work for absolutely everyone.

So overall, I do recommend this book! Try it — at least once, but if necessary, thrice. I think the chances are good that you’ll take away a nice lump of knowledge that, with time, will convert to skill.

4.5/5

P.S

I’ve listened to many podcast episodes on this book over the years, and think that if you’re still thinking about picking up this one, you might want to give this podcast in particular a listen. Neal Bellon comes off rather strong (idk if it’s my normie California ears having a visceral reaction to a New Yorker’s accent or what, to be honest!), and he’ll even say he doesn’t take you seriously if you don’t read this book — but his perspective on this book (yes, he’s done three episodes on it) is full of food for thought.

Hi,

Thank you for writing that thought provoking article. I found Amateurs mind very helpful when I read it about 30 or so years ago. And I agree that the book’s target audience is 1200-1800 USCF. I think that a lot of the criticism of How to reassess your Chess is due to players not realizing that it’s intended for an audience of 1800 at the low end. I feel like a lot of adult improvers tackle it before they are ready and are disappointed because it’s beyond them.

I also think that it is important to realize that Silman himself thought that the best way to master chess was to review thousands of master games and learn patterns. But he understood that most amateurs couldn’t an/or wouldn’t follow such a regime. So the “imbalances” system was intended as a substitute. A workaround to help amateurs who wanted to enjoy the game and improve but who lacked the time and dedication to do the real heavy lifting. He expressed this many times in his chess .com articles. Al’s he explains it in his review of “Move First Think Later” where addresses Hendricks’s criticisms of his methods. Unfortunately the links on Mr. Silman’s homepage no longer work. But fro the way back machine, you may enjoy this if you haven’t already seen it. I leave you with:

https://web.archive.org/web/20230719215407/https://www.jeremysilman.com/book-review/move-first-think-later/

https://web.archive.org/web/20230719215407/https://www.jeremysilman.com/book-review/move-first-think-later/