Book Review: Simple Chess by GM Michael Stean

Possibly the best introduction to positional thinking in Chess

Bona Fides

First off, I am indebted to the Perpetual Chess Podcast for doing a Books Recaptured episode on Simple Chess, so I encourage all of you reading this review to also listen to that podcast episode.

Secondly, if you’re looking for a free study companion for this book, you should check out The Abysmal Depths of Chess blog article series on the games contained in this book. Jonathan includes a few notes here or there about what sticks out to him in these games, and I found this helpful to me personally.

After listening to the Perpetual Chess episode, I decided to pick up the book on kindle. I wouldn’t study it in earnest for almost a year, but it was dirt cheap. I did initially try reading it, but I hadn’t gotten into the habit of using a chess board (either physical or digital), so I was not really able to follow along with what Stean was saying. So, I “shelved” it and only came back to it a year later when I decided on a whim to actually read it for real.

Now that I’ve read it: Simple Chess is a genuine classic, and I can hardly recommend a book more than I’m going to recommend this one.

Simple Chess came out in 1978 originally, so the historical context is a bit interesting. Fischer became champion in 1972, abdicated in 1975, forfeiting the title to Karpov. Karpov would be playing his first match as World Champion against challenger Viktor Korchnoi in 1978. So the proximity of the games contained in this book to the above three world championship cycles means that Stean was working with some very relatively recent examples and had already identified some of them as important games that we now refer to as classics.

What is Simple Chess?

So, what’s the idea behind Simple Chess? Stean succinctly puts it this way in the introduction:

Don’t be deceived by the title — chess is not a simple game — such a claim would be misleading to say the least — but that does not mean that we must bear the full brunt of its difficulty. When faced with any problem too large to cope with as a single entity, common sense tells us to break it down into smaller fragments of manageable proportions. For example, the arithmetical problem of dividing one number by another is not one that can in general be solved in one step, but primary school taught us to find the answer by a series of simple division processes (namely long division). So how can we break down the ‘problem’ of chess?

Give to of the uninitiated a chess-board, a set of chessmen, a list of rules, and a lot of time, and you may well observe the following process: the brighter of the two will quickly understand the idea of checkmate and win some games by 1.e4 2.Bc4 3.Qh5 4.Qxf7 mate. When the less observant of our brethren learns how to defend his f7 square in time, the games will grow longer and it will gradually occur to the players that the side with more pieces will generally per se be able to force an eventual checkmate. This is the first important ‘reduction’ in the problem of playing chess—the numerically superior force will win. So now our two novices will no longer look to construct direct mates, these threats are too easy to parry, but will begin to learn the tricks of the trade for winning material (forks, skewers, pins, etc.) confident that this smaller objective is sufficient. Time passes and each player becomes sufficiently competent not to shed material without reason. Now they begin to realize the importance of developing quickly and harmoniously and of castling the king into safety.

So what next? Where are their new objectives? How can the problem be further reduced? If each player is capable of quick development, castling and of not blundering any pieces away, what is there to separate the two sides? This is the starting-point of Simple Chess. It tries to reduce the problem still further by recommending various positional goals which you can work towards, other things (i.e. material, development, security of king position) being equal. Just as our two fictitious friends discovered that the one with more pieces can expect to win if he avoids any mating traps, Simple Chess will provide him with some equally elementary objectives which if attained should eventually decide the game in his favor, subject to the strengthened proviso that he neither allows any mating tricks, nor loses any material en route.

I cannot think of a better introduction to the ideas of this book than the one the author wrote himself.

Since the idea of Simple Chess is to break down the game into particular positional elements, Stean uses a lot of grandmaster games that we might well refer to as mismatches. One player is always simply stronger than the other and is able to effect his plan because the opponent offers too little resistance. So, the clarity of the particular idea is very high, and it does appear, well, simple.

That’s the core strength of the book. It really does break things down in such a way that they’re not just intellectually digestible, but even addictive like candy. I finished my way through this book in just a week, because I was so engrossed by the explanations, the author’s humor and wit, and the beauty of the games. It’s incredible to me that this book reads so well 45 years later.

The actual content and organization of concepts is rather concise. After the introduction and a few sample games which give you a taste of Stean’s analytical style, you will learn these concepts in the following order:

Outposts (squares for your pieces to occupy which cannot be attacked by enemy pawns.)

Weak pawns (a pawn that “cannot be protected by another pawn, and so requires support from its own pieces”)

Open files (self-explanatory even to beginners, but a file with no pawns on it)

Half-open files (a file with one player’s pawn on it, representing a target for the other player).

Black squares and white squares (this is more about how pawn structure negatively or positively affects the strength, usefulness, and value of the remaining pieces on the board — and there is a lot of good advice here for players who have never read a book on chess strategy)

Space (e.g. the mobility and responsibility of the pieces in relation to pawn structure).

Pawns are the soul of chess, says Philidor, and Stean should reinforce that in you throughout the course of your reading this book. It should be said that this is not supposed to be an encyclopedia of chess strategy. There are so many things to talk about when it comes to chess strategy and generally this should not be done when introducing chess strategy. So, there’s a lot to be said about concepts which are not touched upon in the book. It’s not meant to be comprehensive. It just whets the appetite for the depths you can plumb in the game.

Even so, the selection of games in this book I just find absolutely fantastic.

Standout games

The first game, Botvinnik - Szilagyi, Amsterdam 1966, is a masterclass in showing how to positionally dominate an opponent — Botvinnik’s control over the light squares is something to behold.

There are multiple famous Fischer games, including Fischer-Petrosian, Candidates Match, Game 7, Buenos Aires 1971 with the famous 22.Nxd7!, though for Stean’s purposes, the main point in including this game is how to play against an isolated pawn. His treatment of this game is indeed a treat.

Another great Fischer game is Spassky-Fischer, the fifth game of the 1972 World Championship, where Stean focuses on Fischer’s strategy against Spassky’s doubled pawns in a model Nimzo-Indian Defense game.

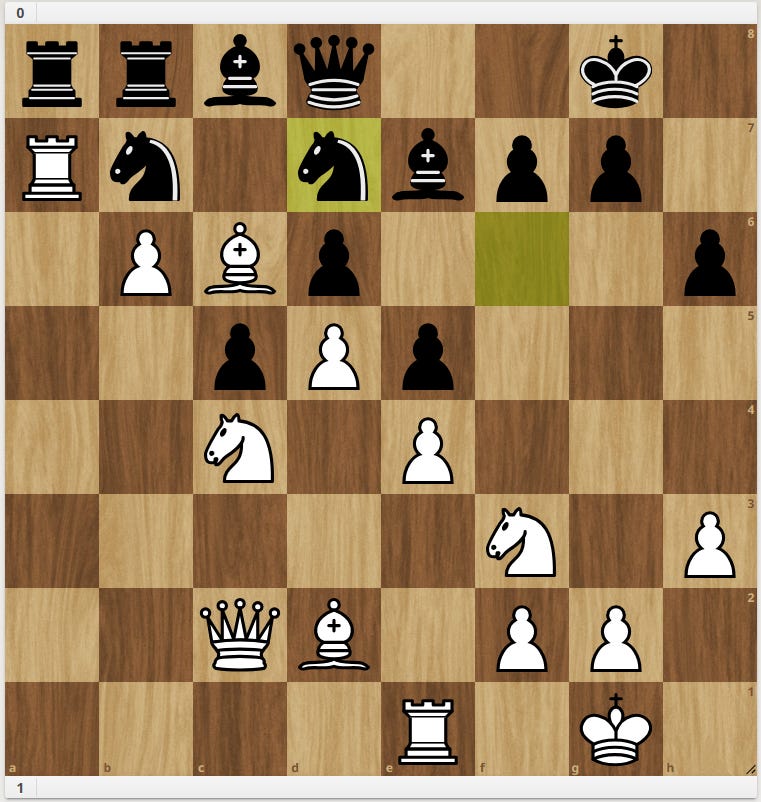

Perhaps one of the most striking games is Karpov - Westerinen, Nice 1974. This is in the chapter on Space. Even so, can you imagine what it would be like to achieve the following position against a master like this? Karpov makes it look so straightforward:

Since the game selection is so strong, I feel I could post my favorite positions from every single game, but I’ll have to let these suffice, and let you do the work of studying every game for yourself.

Conclusion

I’ve sung the book’s praises, so do I have any critiques? I have one: There are many game fragments in this book, and I’m the sort who wants a full game score. So it was a minor inconvenience for me to reference chessgames.com while I was playing through Simple Chess on my lichess study. Other than that, I cannot fault this book, even today.

What are you waiting for? Buy this book. You can get it from Dover Publications, or pick up a copy on Amazon (paperback or kindle). It’s very affordable, around $10, and it might be the best money you’ve spent on a chess book if you’re touching the edge of intermediate chess skill — and if not, it’s still a very enjoyable read! And don’t forget to check out the The Abysmal Depths of Chess companion guide if you’re looking for a bit more.

What a great review..have had it for a while waiting to break it open..will be next in line for me based on your review