Book Review: Max Euwe's Best Games: The Fifth World Chess Champion, by GM Jan Timman

If you're looking for a collection of Euwe games, this book greatly simplifies that choice. And if you're not looking for one, what's wrong with you?

“Why don’t people ever talk about Max Euwe?”

I continually asked myself while reading through the games of the Dutch World Champion. Perhaps it’s because of his short reign from 1935 to 1937, and the dominant form of the revenging Alekhine in their second match. Perhaps it’s because Euwe spoiled many games by inexplicable blunders (something to which he himself admitted). Perhaps it’s because his style is a bit more subtle and well-rounded, such that it’s harder to immediately distinguish his moves from those of another master. Or maybe perhaps it’s because the mythos of the surrounding world champions (Alekhine and Capablanca) prior to the computer era leads others to believe that their losses are almost nearly always flukes. I’m not sure why; but people who haven’t studied Max Euwe’s games are missing out!

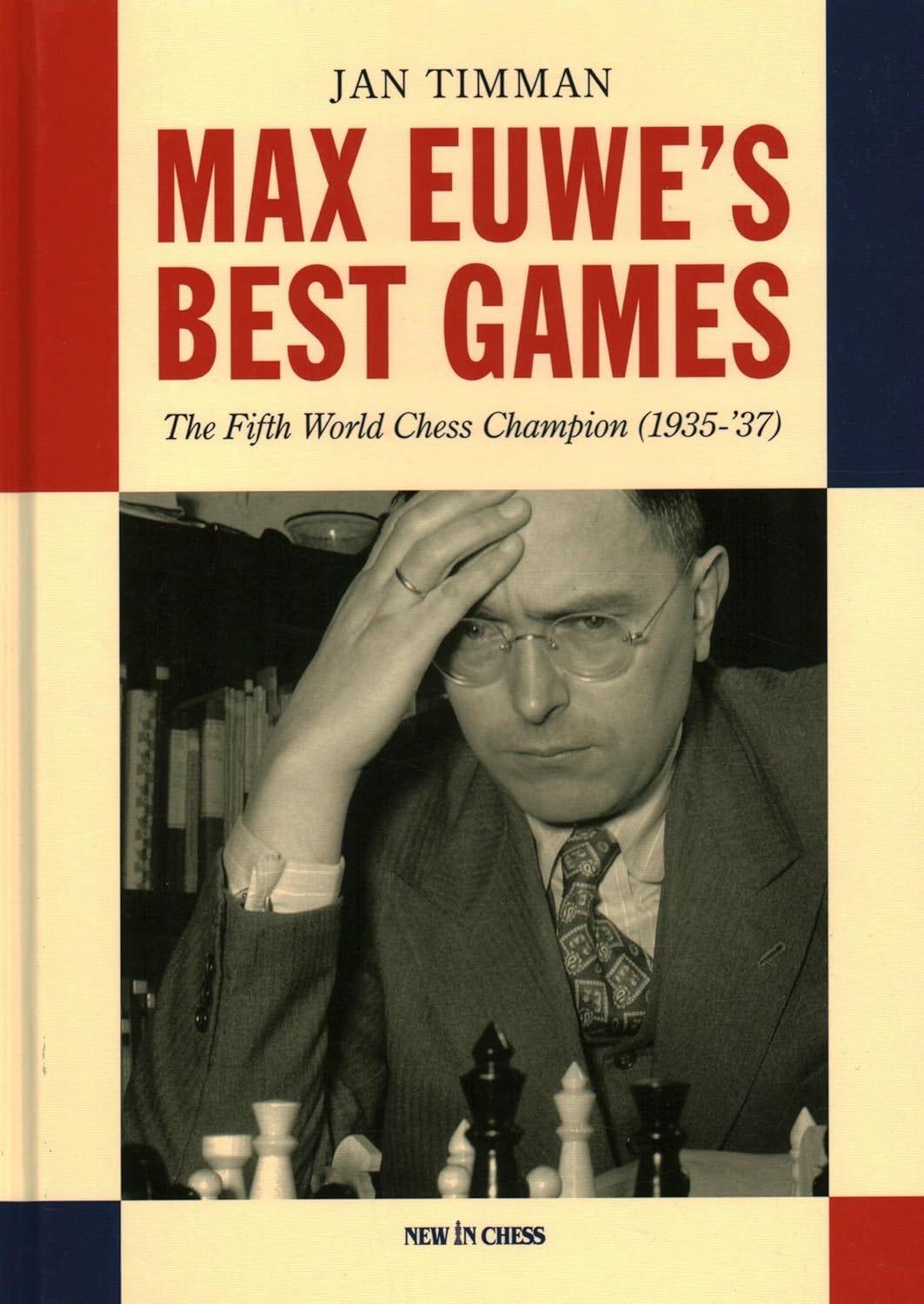

If you haven’t studied Euwe (which to me, sounds like “Er-veh”) before, Max Euwe’s Best Games: The Fifth World Chess Champion (1935-’37) may be your best choice. Author GM Jan Timman represents a generation of Dutch players whose immediate inspiration flows at least in part from the national pride produced by Max Euwe, much like Botvinnik for the USSR and Fischer for the USA after him. Timman in fact was one such person who actually studied under Euwe’s tutelage and rose to become one of the strongest non-Soviet chess players in the 80s and 90s, with the peak of that tenure being his match against Anatoly Karpov in the 1993 FIDE World Championship. In other words, if there’s an authority on Euwe, Timman is probably the best and is more than qualified to show us what we’ve all been missing.

Euwe, 5th World Chess Champion

Max Euwe is a very interesting figure. For a World Champion, he didn’t seem to bleed the 64 squares the same way others did; yet he didn’t fail to make his mark on the chess playing scene, contributing much in the way of chess theory and teaching and writing. Euwe’s name marks many variations still played today, including Game 1’s “Euwe Attack” variation of the Caro-Kann (1.e4 c6 2.b3!?), a trick he pulled out of the cowboy’s hat as early as 1920 against Richard Reti.

Incidentally, that shows a mainstay attribute of Euwe’s career: Rather daring but logical opening choices. Euwe liked to prepare for games and come up with interesting ideas, and seemed to keep up with the latest novelties as Timman’s notes will attest. This is where he compares interestingly to players like Alekhine. Clearly, Euwe was interested in opening theory and developed some of his own concepts, but I think he ends up being a more broadly-prepared player than the 4th world champion. The influence of hypermodernism on Euwe shows more readily compared to Alekhine in the choice of openings he chose with both sides: Euwe’s games in the Nimzo-Indian and King’s Indian Defense show that he was a very flexible player; but Euwe also played the Slav Defense to great effect. This makes his games feel a bit more “fresh” to study.

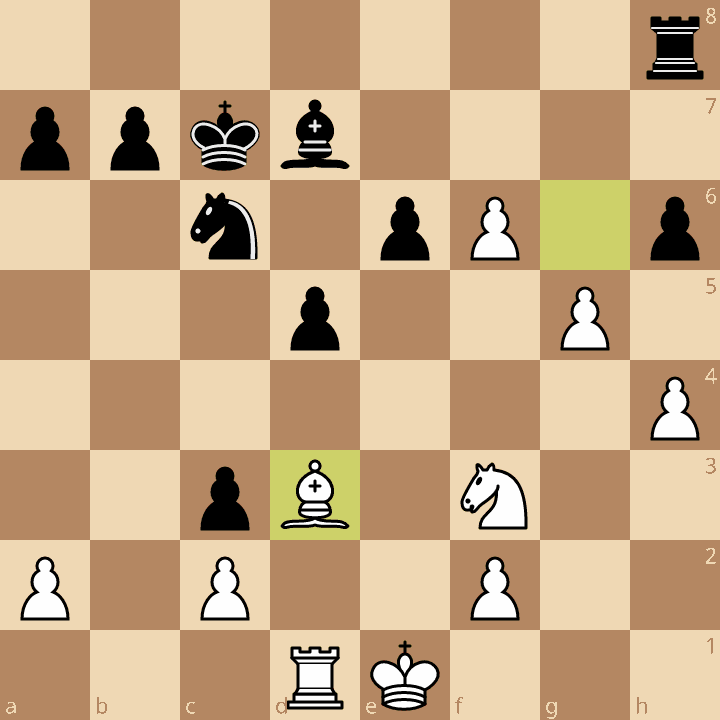

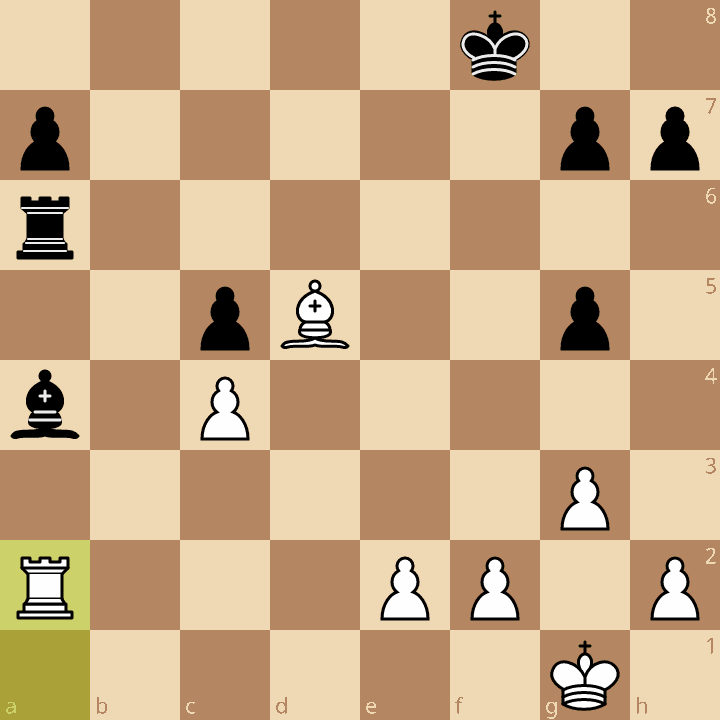

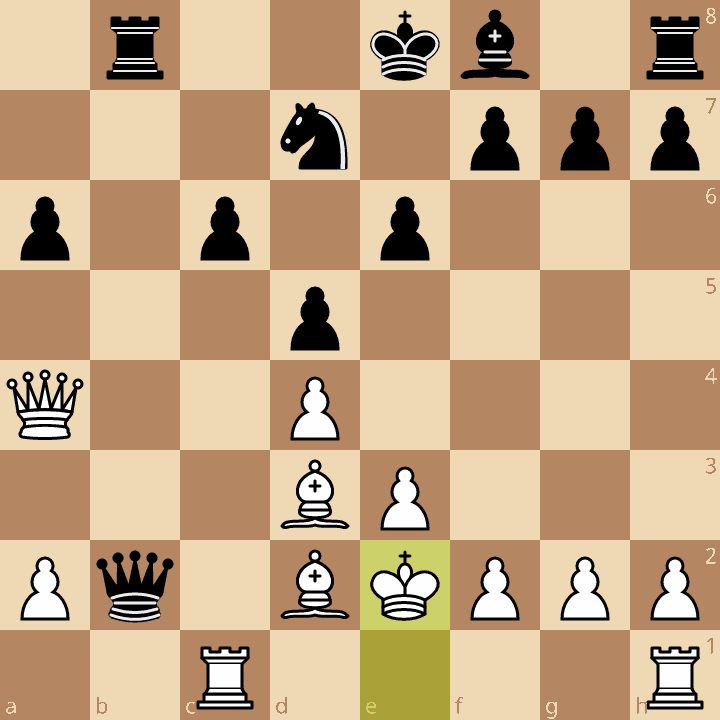

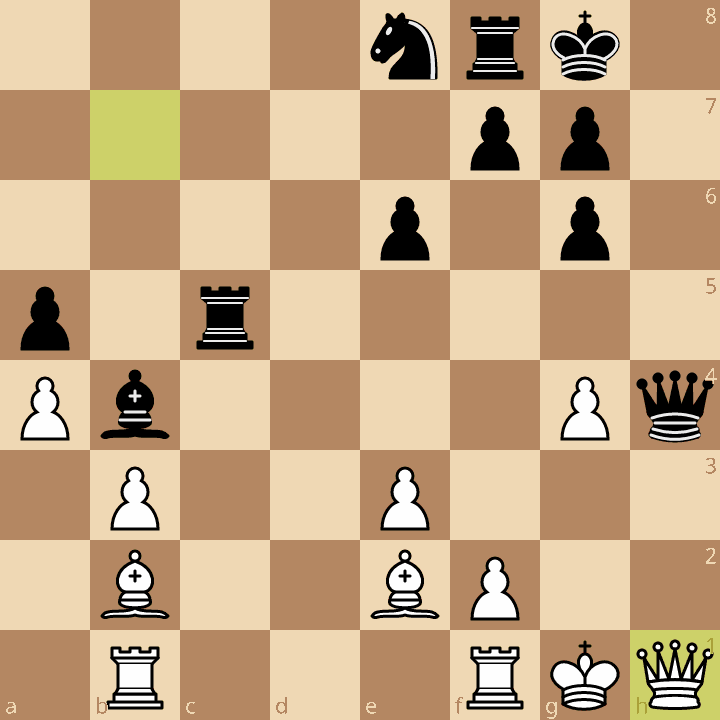

Despite being a player who preferred 1.d4, Euwe was still very much an attacking player. Compared to Alekhine, his attacks come off as less “forced” or brutal. Rather, Euwe’s style seemed more apt toward careful play up and until the opponent made an error which would allow the attack to flow freely. Seeing Euwe turn the screws after a fatal error by the opponent is one of the most entertaining aspects of many of the 80 included games in this collection. For instance, here’s Euwe completely busting a 13-year-old Fischer in a minimatch from 1957 (game 76):

But Euwe had no qualms about trading off into a completely winning endgame if it seemed like the most practical thing to do. Euwe, above all else, emphasized practicality in his play. Timman points out these moments but it really caught my eye in Game 3 (Euwe-Bogoljubow 1921):

So unlike Alekhine! Little comments like this are peppered throughout the book, and I think it’s a nice change of pace that shows why the slightly less-critical but still strong winning lines are often a better choice for the player who desires to be practical first rather than win in the shortest but most complicated moves possible. In another game, Timman points it out the most clearly: “Euwe never aimed for a quick decision in winning positions, but instead sought simplifications and aimed for technical wins”. In this sense, Euwe’s games have a bit of a Fischer-esque feel to them.

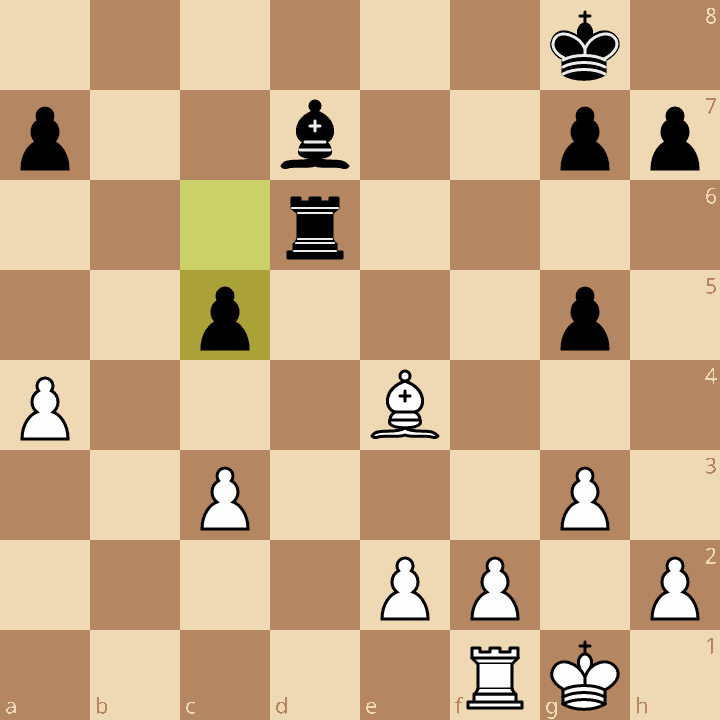

Another occasion where Euwe just chops and chops to win is Game 24 (Euwe - Flohr, 1932). Pay attention to how Euwe patiently creates the conditions for a winning endgame in a same-color bishop endgame before executing it, slicing through Black’s resistance like a hot knife through butter:

Additionally, Euwe’s games show a certain quality of nerve when it comes to playing in sharp positions. Consider this move from Game 30 (Euwe-Alekhine, 1935 World Championship Game 8):

This 15.Ke2! by Euwe shows remarkable and instructive confidence against Alekhine, an attribute of character that most certainly aided in his well-deserved victory as he became 5th World Champion.

Since that championship match in many ways represents the zenith of Euwe’s career, Timman makes sure we get to see more. Consider this position from Game 32 (Euwe-Alekhine)

Here, and in many other games, Euwe makes a practical choice that isn’t the best — Timman calls it “a very deep trap, but not ideal from a technical point of view”. But it doesn’t stop 27.c4!! from making a huge impression, and the fact that Alekhine falls for it with 27.Bxa4 (allowing 28.Bd5+ Kf8 29.Ra1 Ra6 30.Ra2!) means we can still dream of beautiful games in today’s computer era.

Timman concludes this match with the extremely fitting “Pearl of Zaandvoort”, the most-heavily annotated game in the book up to this point. The entire game is incredible to see, so I won’t spoil it — either watch a recap online or, better yet, read this book and play through it and the analysis for yourself. Suffice to say it’s one of the best games of chess I’ve ever seen in my life.

After the title

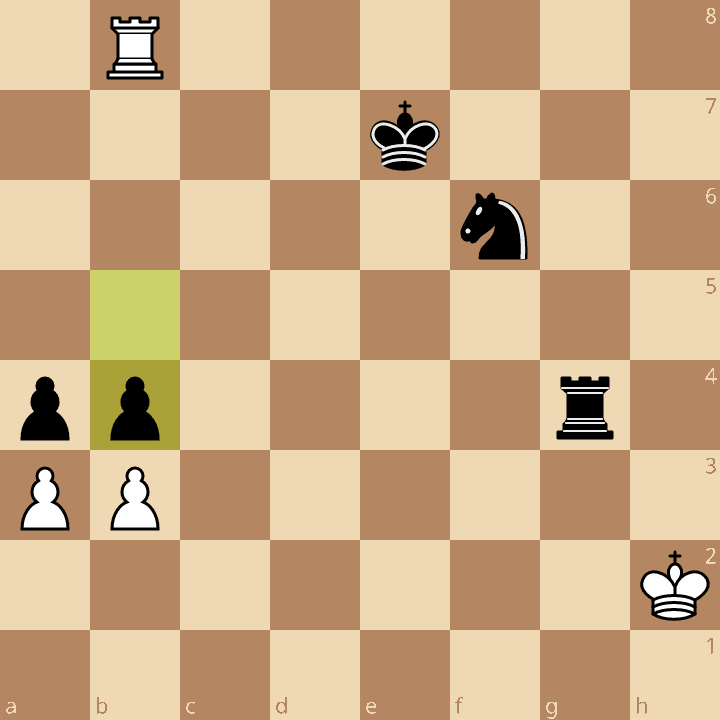

Euwe’s games later in his career, after he loses the championship to Alekhine in the revenge match, remain instructive, though it’s clear that he is a bit past his prime by this point, and therefore the gap of time between each game in these later chapters tends to increase. Nevertheless, Euwe’s beautiful ideas continue to shine in the second half of the book. While Euwe’s tournament results among the world’s top players diminish over time, this doesn’t stop his games from concluding in beautiful ways (Game 78: Sliwa-Euwe, 1962)

This cool move is one of many examples in the book. My joyous observation from reading this book is that Euwe’s games show a certain sort of mirth that I haven’t found in many another player’s games. This book has certainly given me the most spontaneous laughter from the sheer cheekiness of a player’s moves. I have burst out loud chuckling at these moves many times while reading my way through.

For the learners

Timman’s annotations make frequent use of the word “systematic” to refer to this style of principled play that Euwe engages in when it’s time to convert an advantage. Here the reader should pay attention; but also Timman occasionally sprinkles other good advice throughout the book. While it’s not nearly as deeply-annotated as, say, Ding Liren’s Best Games, and while Timman seems less intent on the didactic angle, there still a lot for the adult improver to benefit from. In particular, Timman’s advice about the endgame can be rather illuminating. He has a keen eye for pawn majorities that should not be missed. Where Timman says “preponderance”, you should ponder the position in question.

Critiques

If I have some critique, it’s that perhaps too often Timman refers to “the computer”, and speaks matter-of-factly about a lot of variations that are not easy for an amateur to find. But in general Timman’s analysis and annotations strike a decent balance between focus on “the truth” and letting the chess speak for itself.

As an example of this detraction, in this position (Game 43, Saemisch - Euwe, 1937):

At the end of this analysis variation, Timman simply states “White gets an advantage in the endgame.” This position might offer an advantage to a player, but one is hard-pressed to see how big it is (in fact, it’s not big at all). A club player in the 1600s is probably the lowest level who could possibly see why this endgame is good for White.

Sometimes he will give a long variation with barely any notes but a very confident conclusion, which perhaps betrays a reliance on computers to tell the story, which I find to be rather unhelpful. Thankfully, this habit is typically relegated to relatively distant variations so the reader is unlikely to lose the thread of the actual game.

Also, this may be a generational difference, but this book definitely ends anti-climactically in the same way that many older chess books are prone to. It would have been nice to have heard some concluding thoughts from Timman, because I’m sure he could have spent and spilt more words on the end of Euwe’s career as a chess player. That said, the 80 games included in this collection do sort of tell the story too, so this shouldn’t be a turn-off for the prospective reader at all. Just noting as more modern books often find a more graceful way to land the plane these days and this one felt abrupt.

Conclusion (buy this book)

In my experience the pacing of the book was well-set; though it’s clear that not all games were equally deserving of inclusion in the book, Timman balances this by paying very special attention to the important moments of each game and not getting to bogged down in all the miscellany of things like opening theory — a nice light touch compared to some other books I’ve read. Since it’s a historical survey of the player and not the openings, the most benefit will come from the middlegames and endgames that are analyzed.

By the end of the book, I think most readers will see that Euwe is criminally under-appreciated and stands as one of the great players without whom we would not have been enjoyed the timeless beauty of our beloved board game. Timman does a great job; this book comes off as a sort of passion project for him as Euwe was one of his heroes. Besides this, it doubles as an excellent, perhaps definitive game collection of an important figure of the history of the game that any student of the game should most certainly read.

Thank you for the review! Just yesterday I read your post in the morning and went to visit Max Euwe Center in Amsterdam in the afternoon! I wanted to buy this book as a souvenir, but unfortunately all English editions were sold out, only Dutch ones remained. Still, I greatly enjoyed visiting that museum!