Book Review: Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ A collection of Fischer's thoughts and analyses worth studying 50+ years later

Thank you to Silman-James Press for a review copy of this book.

There’s a brief moment in the book Bobby Fischer and His World which recaps Fischer publishing some scathing criticism of the games played by Kasparov and Karpov, accusing them of prearranging the games. To support this critique, Fischer provides some analysis showing some errors in the games played. It was one of the more interesting parts of Fischer’s post-world championship story, and I wondered if author John Donaldson was going to leave this thread un-pulled or not. It was a fascinating teaser.

I don’t have to worry any more.

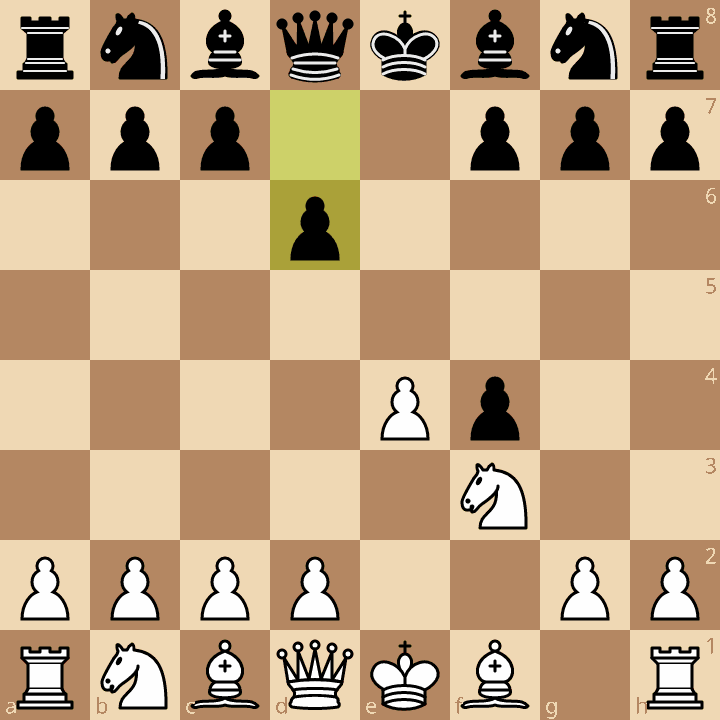

Inside the Mind of Bobby Fischer: Revisiting His Writings and Annotations is a massive collation of Bobby’s analyses and writings that didn’t appear in book form. This includes magazine articles in American Chess Quarterly, Chess Life, Boy’s Life (the Boy Scouts publication), the drafts for My 60 Memorable Games, and even appearances on 1970 Yugoslavian television. One really neat moment I enjoyed was reading Fischer’s article A Bust To The Kings Gambit, where he claimed that Black wins by force after 1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 d6!?. It was enjoyably enlightening to see this article published in its entirety (with some clarifying notes from Donaldson).

Beyond analysis, Fischer wrote many articles where he discussed other players, and these come together to give a fascinating impression of Fischer’s thoughts about his chess-playing contemporaries, as well as players as ancient as Staunton, Morphy, and Steinitz; and of course, Fischer talked about how to get better at chess. In the case of Steinitz, we get many analyses of his match games with Dubois, which shows to really evince Fischer’s love of the first American World Champion’s ideas about the royal game.

As Fischer had opportunity to write and speak through many different outlets, this means Donaldson is able to draw out the nuance of how Bobby talked about chess to audiences of various skill levels. From the perspective of anybody who desires to teach others about chess, I find this rather useful and inspiring. Fischer was known for his reclusive behavior, but in fact he was a very effective communicator regardless of who he spoke to. This is an ability everyone who desires to spread the love of chess should have.

Like his previous entry, Donaldson spends a lot of time filling in previously obscure gaps. To wit, the book boasts 116 annotated games, most of the analysis being Fischer’s, though a few other analysts show up as well. Donaldson sometimes brings his own analysis and commentary, in cases where the historic evaluations are over-ruled by the engine, but by and large he lets things stand on their own. There are hardly any conclusions that are based on or refer to centipawn evaluations — a welcome difference from the mounds of chess books published today that simply bow before Stockfish.

With its focus on his notes, the book reminds me somewhat of Alexander Alekhine’s analysis and the instructive nature contained therein, but Donaldson is quick to note in the introduction that, “unlike others, Alekhine for example, Fischer honestly admits when he missed something and doesn’t pretend to have seen things he didn’t.” In other words, for those wanting to learn the art of analysis more deeply, Fischer is one role model not to be missed, and this quality can be seen in his annotations from time to time.

It is well-known that Fischer’s strong personality earned him a lot of criticism from his grandmaster contemporaries, and he was not given a warm reception by players like Mikhail Botvinnik or Samuel Reshevsky. Yet, in Fischer’s writings about other players, including Botvinnik and Reshevsky, he maintains an admirable objectivity, appreciation and assessment of their skills and abilities. Reading through the whole book and his analyses of games and people, Fischer’s objectivity remains one of the most instructive aspects of his character, and it’s one that many improving players could learn from to imitate.

Because this collection of games is “accidental”, and not a curation of exemplary technique written by historians, we get to see Fischer make mistakes in his games and his own analysis. Additionally, because the sources themselves had distinct intended audiences, this means we get a more-or-less organic view of Fischer’s mind when it comes to chess — how he sees it in relation to other readers and himself. Donaldson fills in the details here and there at the beginning of chapters and in between analysis, but by-and-large this book is meaty with game scores and sometimes entire other games are quoted in analysis of the main entries. The opening theory isn’t what matters here, though Fischer sometimes shares a little of his internal book. Rather, playing through these games over time should expose the reader to a lot of good ideas that were normally executed rather well. Like its predecessor, it is not a best-games collection, and that’s part of what makes the book work so well especially for club-level players.

Ultimately, I must recommend this book for any club-level player looking to get a full-orbed picture of Fischer and the game of chess. His analysis is instructive, incisive, and, perhaps best-of-all, completely human. The book also fits in so nicely with Bobby Fischer and His World that I shouldn’t fail to recommend it to lovers of that prior book, with its hagiographic emphasis. This is a Bobby Fischer book for virtually anyone. So I think everyone should get it.

Look forward to this book . Excellent review