Book Review: How To Win At Chess By Levy Rozman (AKA GothamChess)

Levy Rozman Teaches Chess

A huge thank you to Omar Mills, who ordered this book for me so I could read and review it!

tl;dr - Should you buy this book for that chess fanatic in your life?

If you’re not a chess player yourself or aren’t interested in reading a lot about what’s in the book, and just want to know “Christmas is coming up. Is this a good book to get for my child/friend/partner under the rating of 1200?”, I would say that this is not a bad choice at all. If they’re a big fan of Levy Rozman (aka GothamChess), then this is probably a great gift idea. It’s so easy to read I think that if you had someone who wanted to learn the game and really just get the basics of the basics down, this is probably one of the nicest options available. It’s certainly the most readable one to come out in a long time.

Who is Levy Rozman (aka GothamChess?)

As a chess player who made got into the game before the chess booms fueled by COVID-19, The Queen’s Gambit Netflix series, or, uh, cheating scandals involving bogus theories of clandestine devices used for unorthodox communication in the middle of a live-action over the board chess game (I digress), I feel like I mostly missed the boat and initial appeal of IM Levy Rozman, who most people know from YouTube and Twitch as “GothamChess”. Levy boasts 4+ million subscribers on Youtube, 1+ million on Twitch, 350K followers on Twitter (and I’m still not calling it the other name).

For better or worse (and in my opinion, it’s a net good), he is probably the most influential popularizer in the world of chess today. Demographically he’s perfectly positioned: He’s on the young side of millennial and old side of Gen Z, so his reach is broad. He has an enthusiastic demeanor on audio, video, and even in his writing. His YouTube videos can be extremely educational, but they are basically always entertaining. He has created a series of 10-minute videos that give you the very basics of a chess opening, shows you just enough how to handle the little tricks to them, and then encourages you to jump into the pool and flail yourself around until you learn to swim. The “Guess The Elo” genre is something he seems to have created single-handedly, and it can be simultaneously gut-bustingly hilarious and mind-blowingly enlightening. My personal favorites are when he goes through the games and/or analysis of interesting games, often played by top grandmasters.

Levy also takes his fans seriously. Sometimes, in his earlier videos, he could come off a bit harsh to his followers and fans, but my read on him on social media is that he gets it: Chess is hard, and people need someone to teach them and they also need to be reminded of how far they’ve come. Sometimes it seems like an overreaction, but Levy seems to celebrate any Elo gain by anybody who is trying to become better at chess. And he’s put himself on the line too, announcing a push for the Grandmaster title and later announcing that he decided to step away from that so he could focus on content creation. And creating content he has been. It’s an absolute whirlwind. Youtube videos. Chessly. Chessable courses. The Gotham City Podcast. The man has worked so hard to create this online social media empire that teaches people how to play chess and in ten years, I think he’ll still be one of the most popular chess teachers to grace the game.

He is well-deserving of the title “The Internet’s Chess Teacher”. De facto, it is simply a reflection of the truth. That’s part why I’m so intrigued that he went not for more internet content, but instead decided to distill into book form his basic philosophy on how beginner to intermediate-level players (read: 0-1200 Elo, and I’m assuming this is chess.com rapid/blitz ratings) should play to win a game of chess. Given his audience who, I would assume, mostly want to consume his content via digital means, especially by video, it is actually a bit of a bold move to release something in the format of a book. Not that his watchers don’t read! — just that they’re used to getting their Levy-fix via 1s and 0s, rather than the written word.

The Book

Enter How To Win At Chess. Levy’s take on how to teach chess, it’s a bit over 270 pages of words and diagrams designed to take you from beginner level to intermediate level. Does it succeed?

The intended audience consists of players rated from 0 to 1200. I assume that this is a chess.com rapid rating, but it could also apply to blitz ratings. Assuming this is the case, Levy is targeting the roughly 0-90th percentile of chess players on chess.com (which, as of today, consists of 30 million active players on chess.com). The average rating of a chess player on chess.com is 650. Clearly, this book is meant for the vast majority of players, which is so unlike most chess books. And the Lichess rating equivalent? I would say up to 1500 is a good guess

Being a player rated far over the intended audience of this book, I can only give an opinion of how good or appropriate I think his advice is, and in general I think it is rather practical and good for the likely reader — far more nuanced than one might expect.

Before we get to the content of the book, I want to make a note about the quality of the book: It’s excellent. The cover is simple and the design is just slightly abstract. The biggest word on the spine of the book is “CHESS”, which is also the most prioritized word on the front cover. In this sense, it’s no-nonsense. It looks great. The page quality is also wonderful. They’re not super thick, but everything is in color and none of it is flimsy. The diagrams appear to be screenshots from the chess.com user interface, complete with arrows and highlighted squares to help you visualize; and there’s at least one diagram on every page that contains direct chess instruction — and usually two or more. In some cases, up to four, which takes up an entire page itself. Plus…

You don’t need a chessboard to read this book.

I saw Levy reply to a follower on Twitter that the book is meant to be used without a chessboard (which is unlike the vast majority of chess books); and this is technically true. However, the book contains QR codes which link to Levy’s Chessly website, to get into further details or showcase a game that he referenced in one of the chapters, and there it loads a digital board; so if you want the full benefit of what he writes, you’ll need a smartphone to load the links. The Chessly interface is not my favorite, but it’s not poor by any means, and it’s a cool way to integrate his website’s teaching potential into the content of the book. One feature I particularly enjoyed is that in some cases Levy gives and annotates an entire game for you so you can watch the moves and read the notes. This is especially helpful when an example is long and needs to be explained. The notes themselves are not too deep — and I don’t think they need to be, because of the target audience of the book.

The Content

After the introduction, in which the very basics and rules of chess are laid out, the book is divided into two parts, and these are separated by two rating ranges. From the very first pages, you can tell that Levy wants to use updated, practical, more easy-to-understand language in order to better instruct the reader. You won’t need a dictionary to understand the words. It is thoroughly modern vernacular. It’s every-day language.

Part One is for players rated from 0 to 800 (which he refers to as “Beginners”). Part Two (for “Intermediates”) is designed for those rated from 800 to 1200 (and perhaps a bit beyond that).

Part One first starts with how to (literally) win at chess, and discusses the termination of the game: checkmate, resignation, timing out, and abandonment (that is, walking away from your game and never returning, which is a common form of poor behavior in online chess, but rather rare in real life — but Levy shares a rather famous story about an alleged rage-quit that occurred in the late 1800s).

After this, it’s the basics of opening theory (the very basics). Levy recommends a couple approaches for white and for black, but also emphasizes the importance of opening principles: Controlling the center, developing your pieces, castling your king. It’s all generally sound advice that most chess players will have heard if they ever resorted to searching the internet for tips on how to play chess; nothing out of the ordinary here.

After the openings, it’s a discussion on the very basic of basic endgames that a player must familiarize themselves with in order to break out of the 0-800 rating range. He then discusses how games can end in a draw — some of which can be surprising for a new player to learn (e.g. the concept of threefold repetitions, and stalemate, and insufficient checkmating material).

Then there’s a small treatment on the basics of attacking, defending, and capturing. This digs down into the very definition of what an “attack” actually is. This all sounds simple, but I appreciated the accessibility of this advice, because for many new players, this simply is not obvious. The last chapter in Part One is all about basic strategy: Weaknesses, “space”, open and closed positions, etc.

“Space advantage?” or “Activity”?

This is the one chapter where I register any significant disagreement. I will give a disclaimer: I’m not anywhere near Levy’s skill level or knowledge level when it comes to chess. I’m a Class B USCF rated player with the lofty goal of National Master, and that goal is at least three rungs below Levy’s title of International Master. I know that I’m disagreeing with a strong master here:

On page 112, Levy defines space as “the number of squares you control in your opponent’s territory”. I think more accurate is the number of squares behind your pawns, which your pieces can use to maneuver. He does talk about the freedom that space grants to one’s pieces, but his definition may be slightly misleading, because it makes you think about the area in front of the pawns rather than the area behind them. This is not how I’ve seen any other book on strategy explain this concept. In practice, when in reference to pawn structure, this seems like mostly a lexical difference, but it does mean that it could set a different standard depending on how popular this book becomes (and I think it could become very popular indeed!). However, the problem is when you’re talking about pieces (not pawns) controlling squares in the enemy territory.

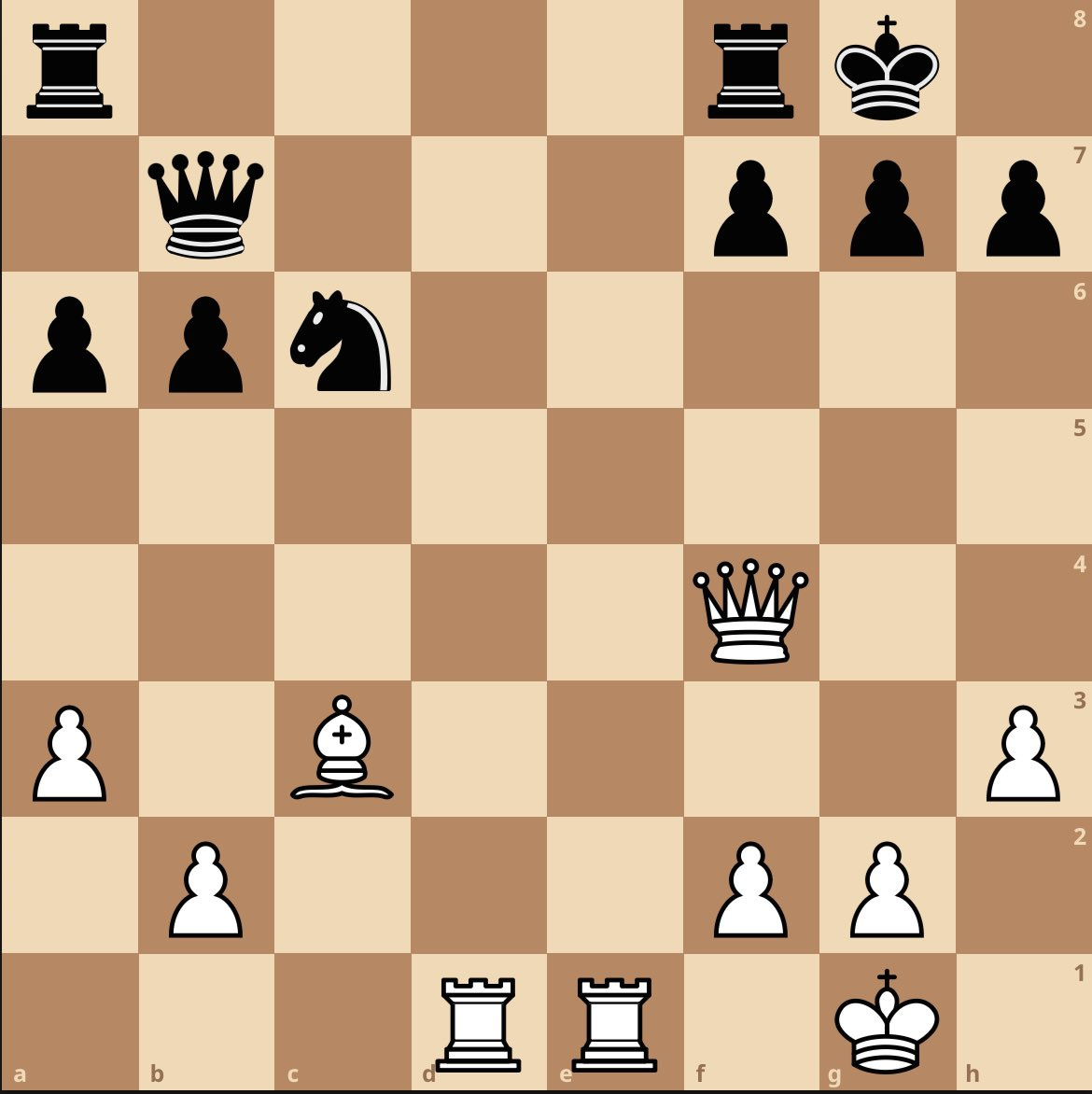

On page 115, the first diagram contains an open position where Black and White have the same number of squares behind their pawns:

I would describe the position as advantageous for White not because of a space advantage, but because of the material imbalance of having a bishop on an open board and actively placed pieces. He’s correct that White controls much more of Black’s territory, but this isn’t due to space, per se — there are no pawns really standing in Black’s way obstructing them from active positions, and White is not oppressing Black’s pieces by way of pawns controlling important squares in Black’s territory. In other words, in this position I think that the advantage White possesses which Levy ascribes to space I would ascribe to piece activity.

This may seem a small thing from an outside perspective, and perhaps it is. And, perhaps the way Levy frames a space advantage is simpler for an <800-rated player to grasp. Since that is his primary audience, I’ll let this be my last word on it: Later treatments of space that an improving player may read will require them to redefine what space is, if they go by Levy’s definition in this particular book. It’s not a dealbreaker by any means, just something I noticed that might temporarily confuse improving players later down the line.

I digress…

Overall, however, I was really impressed with the presentation of every concept: Clear examples, gratuitous use of diagrams (remember, Levy doesn’t want you to use a chess board to read this book!), and the associated content on Chessly (for instance, the Steinitz - von Bardeleben game featuring the famous, if slightly apocryphal, “rage-quit”) all make for a great learning experience. This book contained all sorts of basic principles that I could have used when I was just starting out in the game six years ago.

Once Part One is complete, players can take what they’ve learned and play to improve until they reach 800, or they could just read ahead if they want to learn a little more anyway. Part Two (for “Intermediate” players, which to Levy is defined as 800-1200 rating) recursively builds on the concepts laid out in Part One. Players revisit key concepts, and now, having gained the knowledge and skill of an advancing beginner, learn deeper ideas about the game.

The first half of Part 2 is all about the openings. Levy makes recommendations which I think are practical and designed to avoid having his reader get sucked into the black hole of never-ending chess opening study. There is no deep preparation or analysis to be found here, because players under 1200 don’t need it. Other than talking about the London System, Caro-Kann Defense, or Queen’s Gambit Declined (and some other lines), Levy also makes mention of gambits and gives a few examples of traps or ideas that make them so dangerous to play against and so appealing to the adventurous player who wants to spice up their game. Levy gives Chessly links in the QR codes at the end of each chapter if you want to learn more. Here’s where I register one last small qualm:

When discussing the Vienna Gambit Declined for White on page 141, Levy doesn’t touch on the “main line” of the Vienna Gambit, which is in fact, the Declined variation with 3…d5! Luckily, this is not an omission in the book but rather (in my opinion) an omission on his website Chessly, where his QR codes send you if you want to dig deeper into any given subject covered in the book. To be fair to Levy, the moves 3…fxe5 and 3…d6 are more popular at these Elo levels, and thus, he is covering the most popular lines of the opening for players of that level; but when someone graduates to above a certain rating level, they will eventually be surprised by 3…d5, which is far and away the move to fight against the Vienna Gambit! Even just a mention about this move would be good.

After the openings, we’re back to the endgames, and they are much more advanced this time around. Levy goes into some detail talking about basic endgames such as King and Pawn endgames and Knight vs Bishop endgames. He even shows the technique for stopping a pawn from promoting by using the queen even when the enemy King is defending. Plus, practical advice on how to play endgames. Again, the sort of thing that I could have used when I was playing chess at this level when I first started out!

Then comes a treatment on tactics (short-term combinations of moves intended to win something — either the game, or a piece, or even just a pawn). Tactics are where 99.9% of games at this level will be decided, so this is an important chapter, where Levy covers the basic thinking process one must use to find tactics in a position (he terms it CCA: “Checks, captures, attacks” — the usual terminology is “CCT”, where “T” means “threats”, but this is another case of two different words for the same thing). He discusses longer checkmating sequences, tricky removing-the-defender tactics, even the idea of zwischenzug, or in-between move. His overall advice is nothing new, but always timeless: If you want to get good at chess, you need to do lots of tactics — thousands, even.

The last chapter will appeal especially to those players becoming higher up on that 800-1200 intermediate rating spectrum that Levy has provided, because it’s a deeper treatment on intermediate strategy, piece by piece, discussing the concepts of pieces trades (even how these plans are specific to certain openings) and starting to think more “positionally” about the game overall. This chapter I found surprisingly nuanced and enjoyable to read, full of strong advice, the sort of things that I think would very much help a player take their first steps beyond “intermediate”. The final part of the book is a little glossary to describe and define a number of words and phrases you might find in the book.

Conclusion

So, is this book good? I think it’s great! It’s very well-written, and intended for anybody to pick up and read and learn how to play the game. Does it contain anything that a player rated 1400+ wouldn’t know? Probably not! But I do think that it’s probably perfectly targeted for the 0-1200 rating range — this goes double if you (or the person you’re shopping for) is a big GothamChess fan. Is this book going to be the next Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess? Possibly. Time will tell, but I think that Levy’s created a great contribution to chess literature that easily fills the niche of being someone’s first chess book, and it comes in a beautiful package with lots of diagrams, and it’s certainly the most accessible book I’ve read on the basics of how to play chess in a long time. For most people under 1200, this would be a great gift to get for someone else, or to treat yourself to some chess edutainment with.

Thanks for the review. I'll grab one as a Christmas gift!

Very nice and comprehensive write up. From what I can tell this book will fit an audience that is missing books like this. As someone who did read the fisher teaches chess book when I first started, this looks to definitely challenge that for position on the shelves as well as offer information I’ve yet to learn...in fact type in fisher chess book in Amazon and Levy’s book pops up above it on the list order. Thanks for the write up