2025 Sacramento Chess Championship Recap

A slow but steady climb back into form

It’s been a while since I posted game recaps. I expect most people follow this newsletter for book reviews, not my own game reports. Nevertheless, with some encouragement from readers I know in real life, including one reader who I met by chance at a local tournament, I’m here to recap some of my games. This time, five of my six opponents were veritable children! And somehow I managed to escape away, once again, with 3/6! My losses this time were… well, pretty poorly fought. I lost two games in bad fashion with Black the first day, and they both featured some faulty thinking. Since these were basically blowouts, a critical moment or two should suffice before I self-aggrandize with some wins in the English opening.

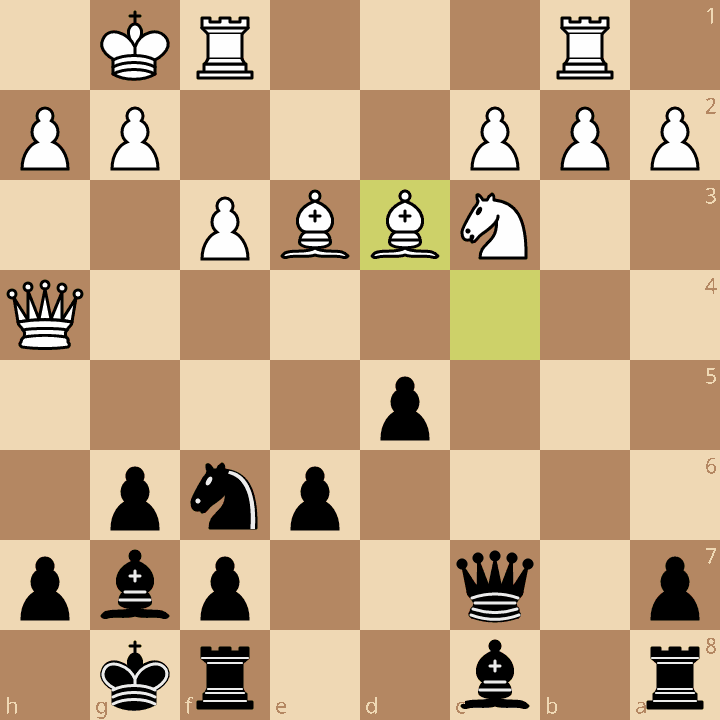

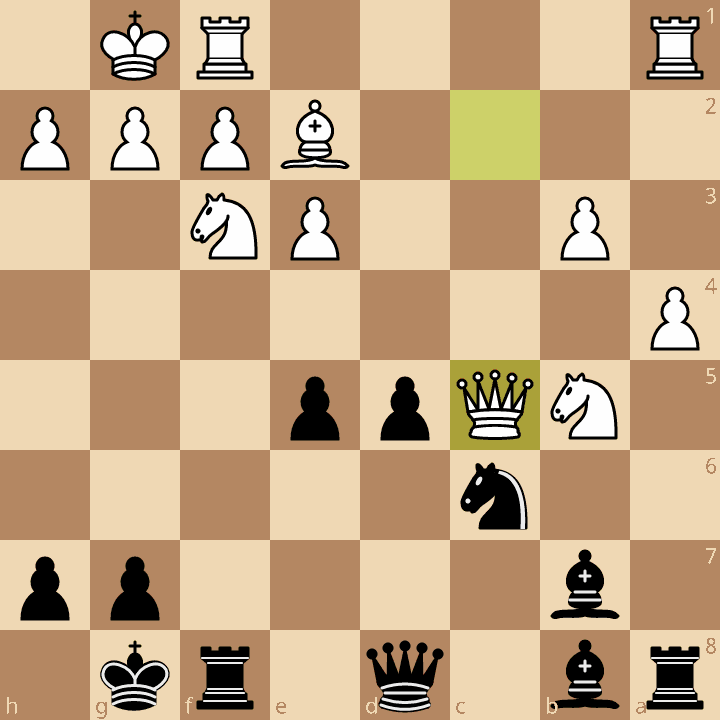

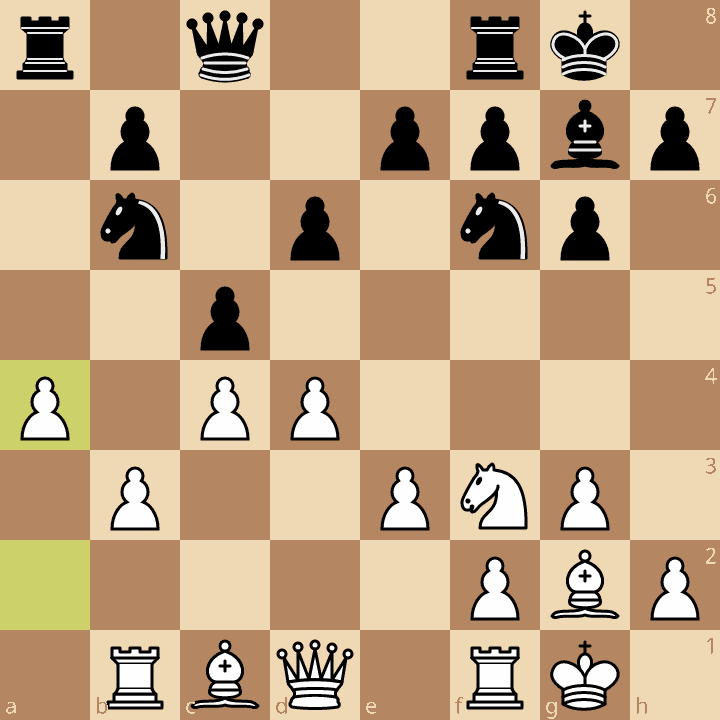

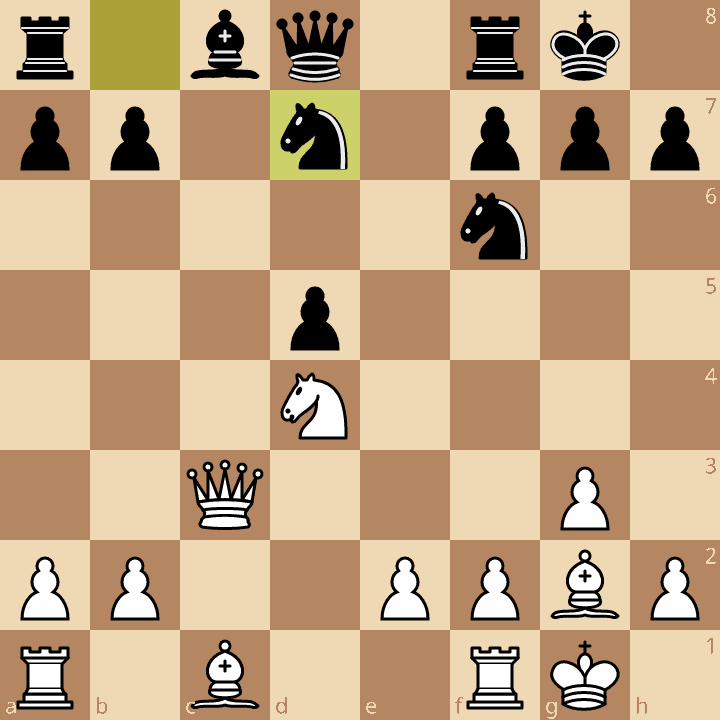

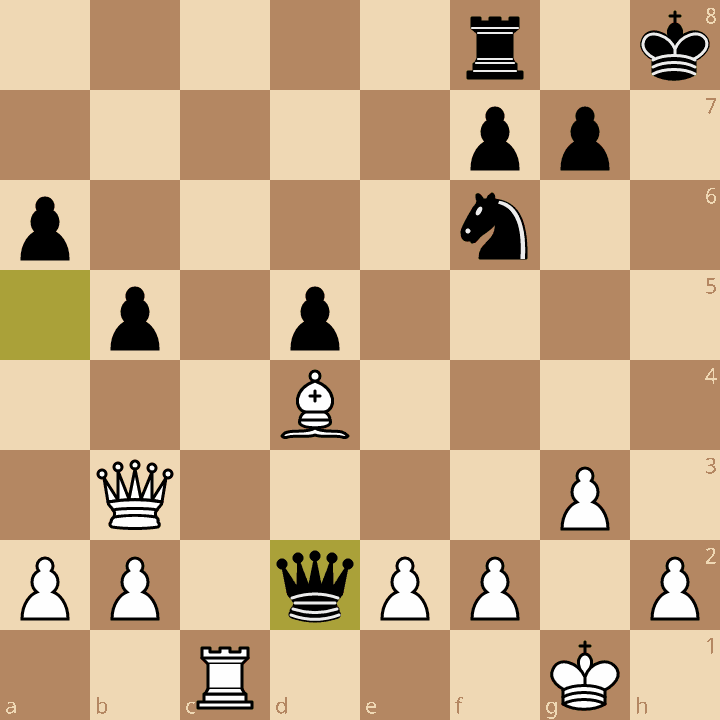

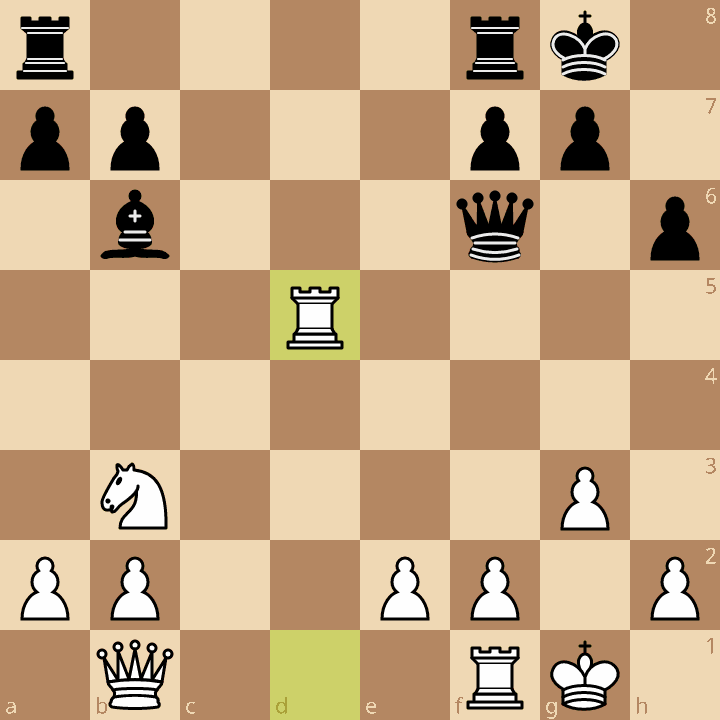

Game 1: Black vs 1893 USCF

This Sicilian turned out pretty nicely for me thanks to some suboptimal opening play by my opponent. I’ve got a nice center, active bishop on g7, and White’s structure leaves a bit to be desired. But there is a threat in this position and I completely missed it. To stop 16.Nb5 I can play Bd7 or a6. This would prevent White’s plan to cause trouble on the queenside. Alas, thinking of setting up a trade to get rid of my relatively poor bishop on c8, I played the stinker move 15…a5?! After 16.Nb5 Qd7 17.Bc5 I panicked.

This position, while visually uncomfortable for Black, wasn’t nearly as bad as I made it out to be. I spooked myself into thinking I was definitely losing an exchange here, and I’m not sure why. Now it’s obvious that 17…Re8 completely avoids the threat. If 18.Nd6, there isn’t a problem, I can just play 18…Rd8 and if 18.Bd6, then 18…Rb8. Perhaps I was yet to shake off some initial rust. I played 17…Ba6?! deliberately sacrificing the exchange. My logic was that I’m getting an unopposed dark square bishop, and maybe it’s possible for a stronger player to draw such a position, but not me. I collapsed in the next 14 moves:

Ouch!

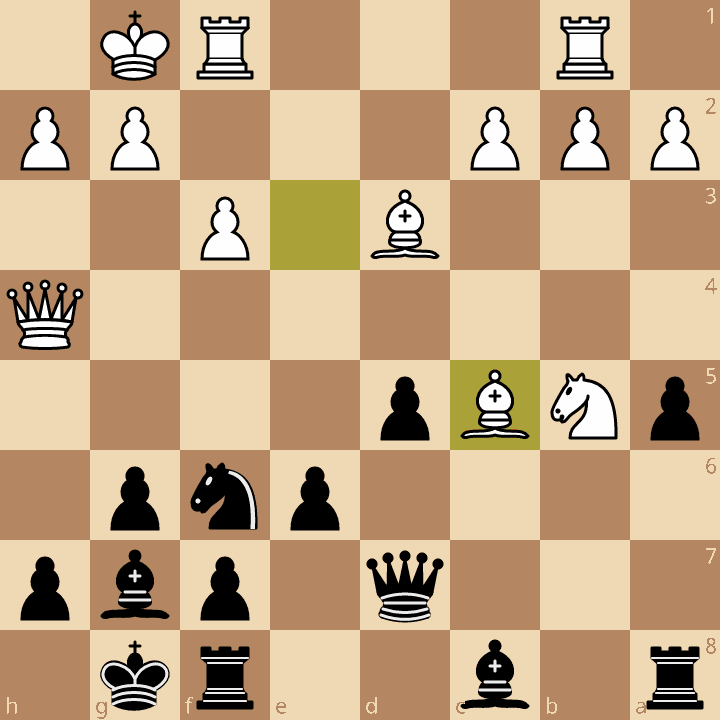

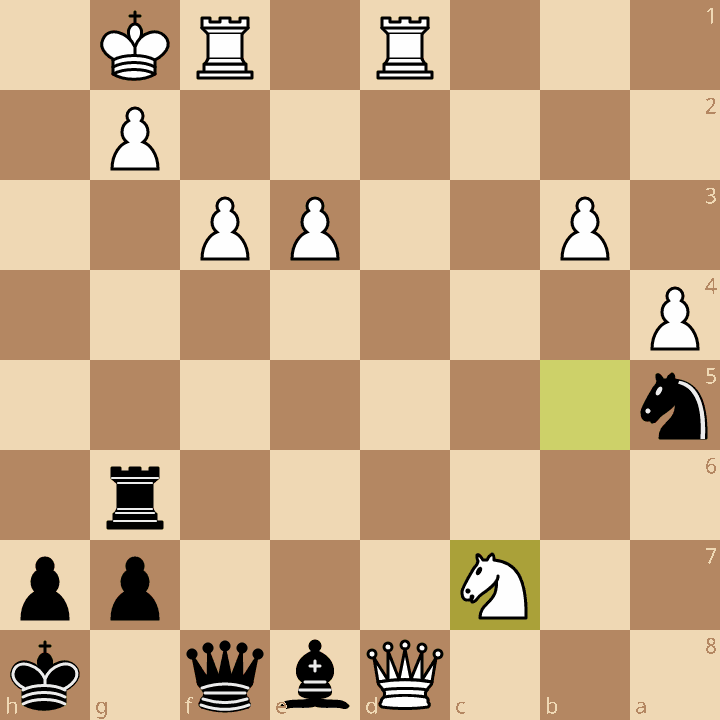

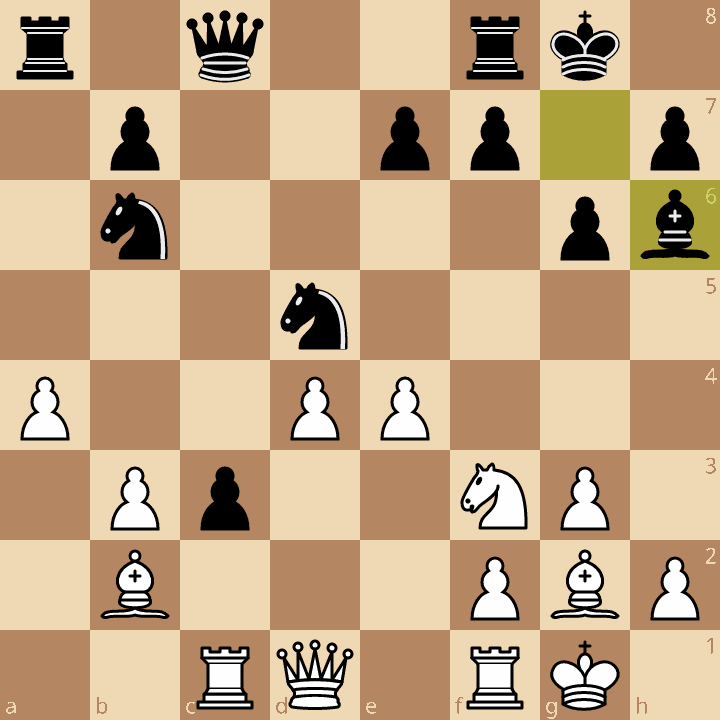

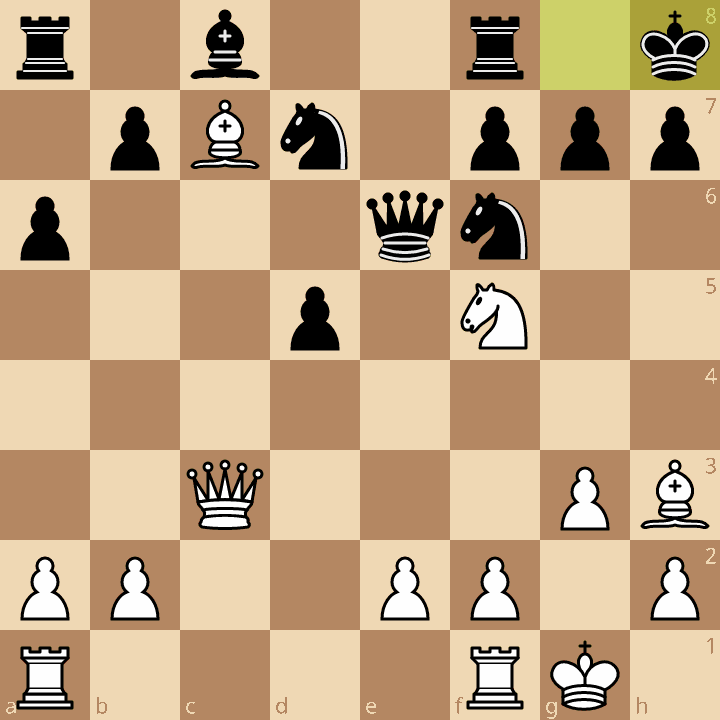

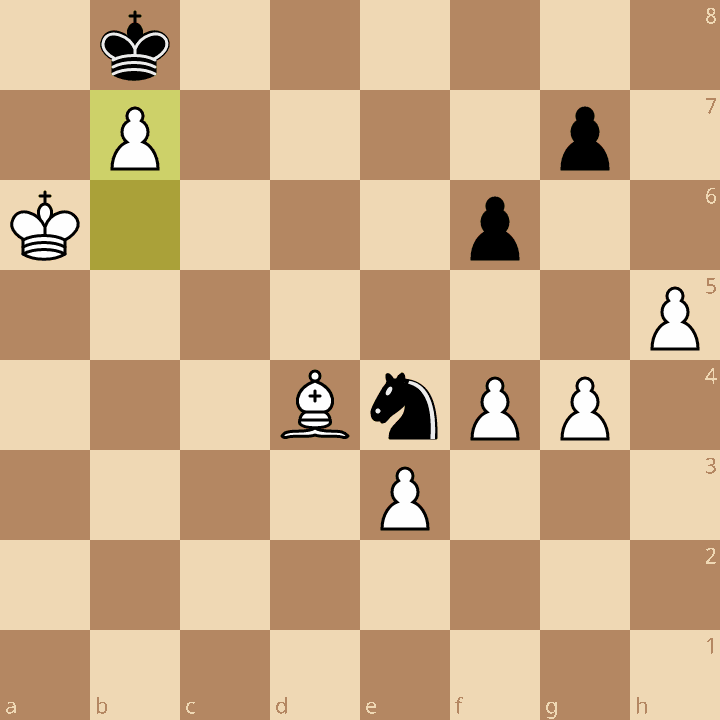

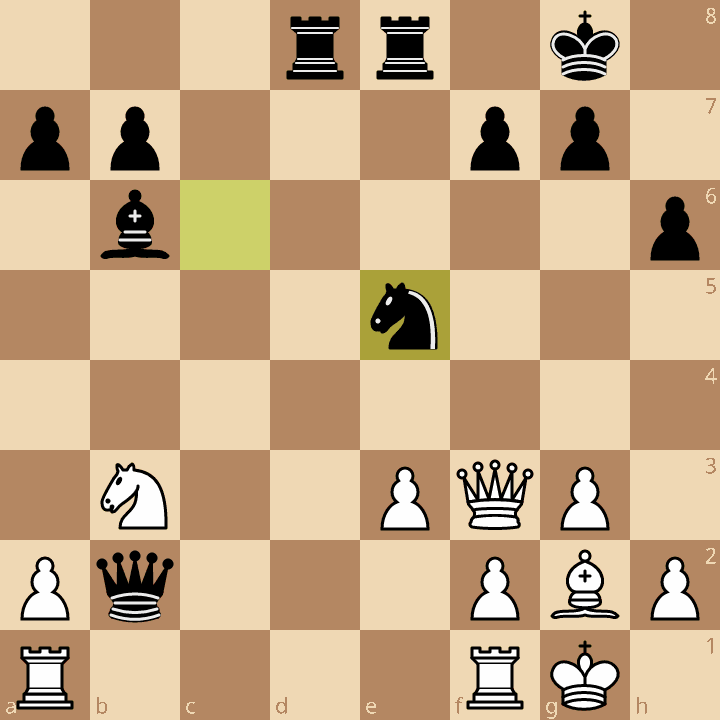

Game 4: Black vs 1678

This game I felt I had even less of an excuse.’

In this game I had a relatively standard Benko opening, but I somehow forgot my prep in this particular variation, and so found myself in unfamiliar territory shortly thereafter and was playing rather unconfidently. On the 17th move of the game I was confronted with this position:

Here White is threatening to win the c5 pawn, and I wasn’t sure how to handle it. Voluntarily placing the queen as a target of a pin and/or skewer was not my cup of tea, and it wasn’t at all clear to me that White wouldn’t be dissuaded from winning this pawn as it was. Now, what I should have played was simply 17…Nb4, stopping White’s threat bluntly. But for some reason I was particularly bothered by the ugliness and possible long-term indefensibility of that pawn after 18.Bxb4 cxb4. So instead, on a whim, I went with my gut to sac it with 17…e5? After 18.Bxc5 Nxc5 19.Qxc5, I was at a crossroads.

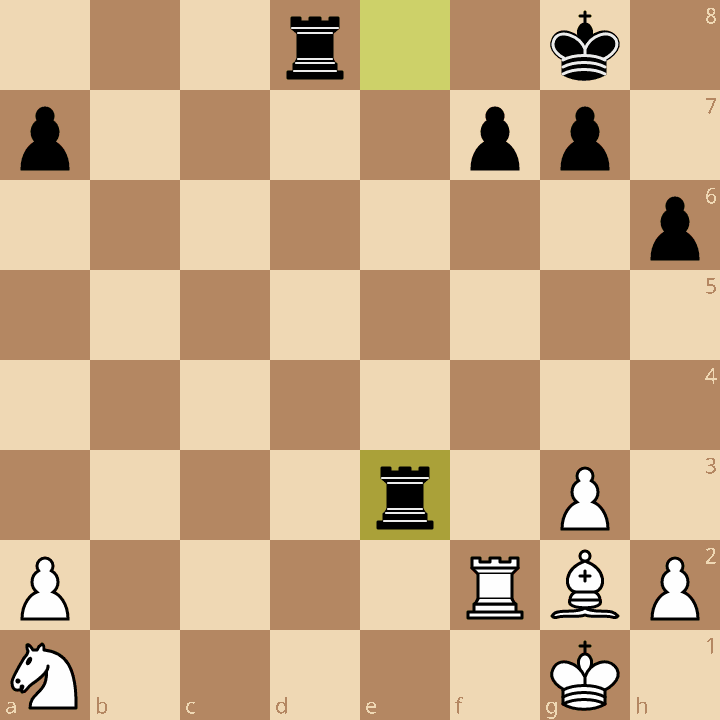

I felt that White was going to play Ng5 threatening Ne6 with a nice material gain. I couldn’t see clearly and was starting to feel the strain of the tournament (as this was the fourth game of the day, and I had up to this point been playing for close to 8 hours already. In fact Black’s position is already pretty bad here, but I managed to make it worse(!) with the further exchange sacrifice 19…Rxf3?? After 20.Bxf3 e4 I thought I was finally getting somewhere in the position because of the center opening up for my long-range pieces. But my opponent found the nice counter-sacrifice 21.Bxe4!! dxe4 22.Qc4 Kh8 23.Qxe4 and my collapse completed itself a few moves later when I made a faulty sacrifice to try for a three-fold repetition but found myself one tempo short of the required moves to get there.

Again, the scene of the crimes:

Ouch-ouch.

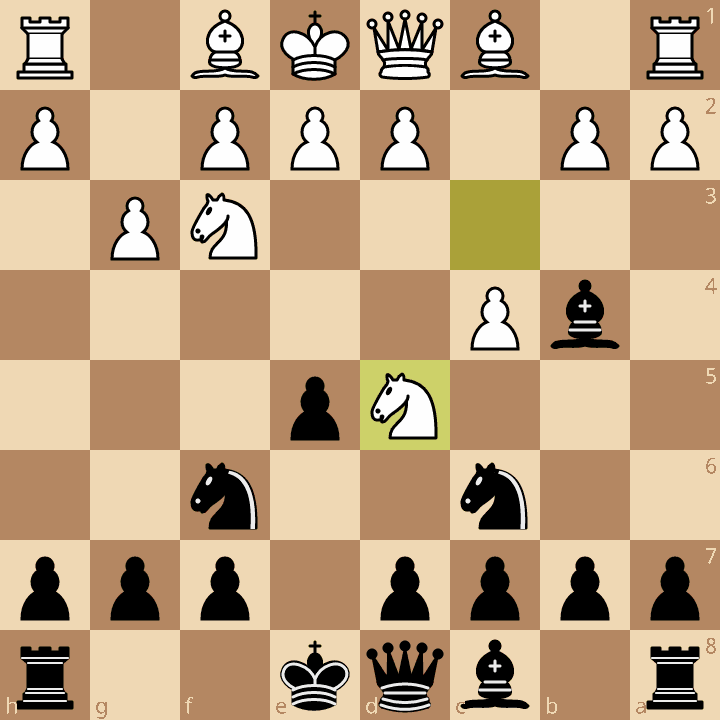

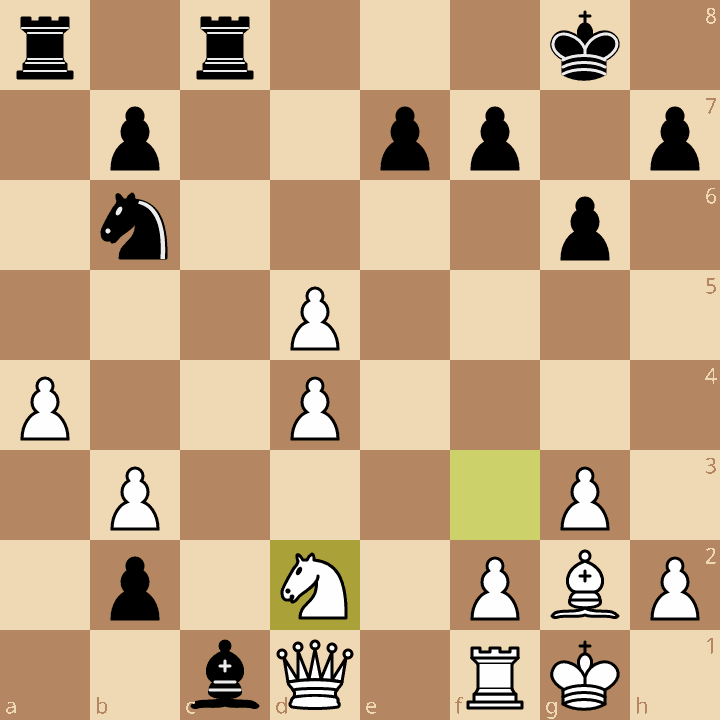

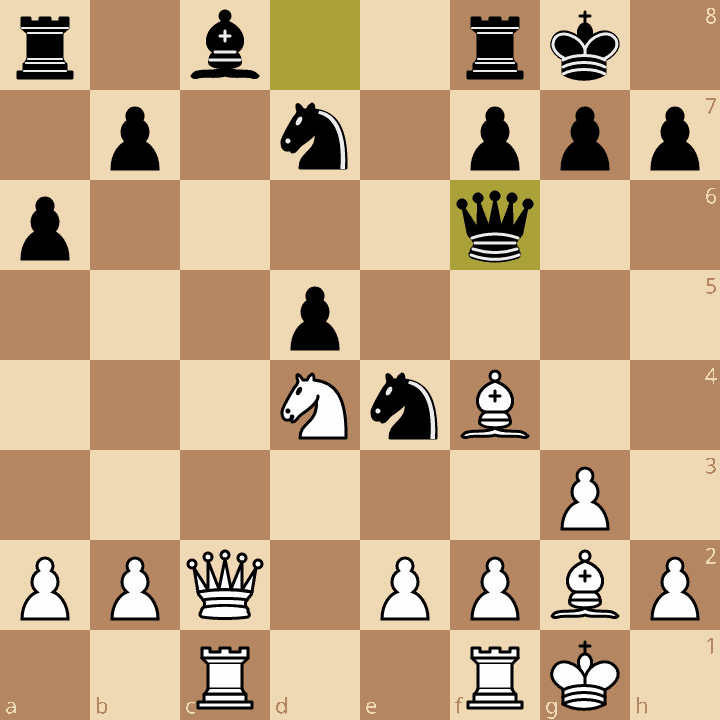

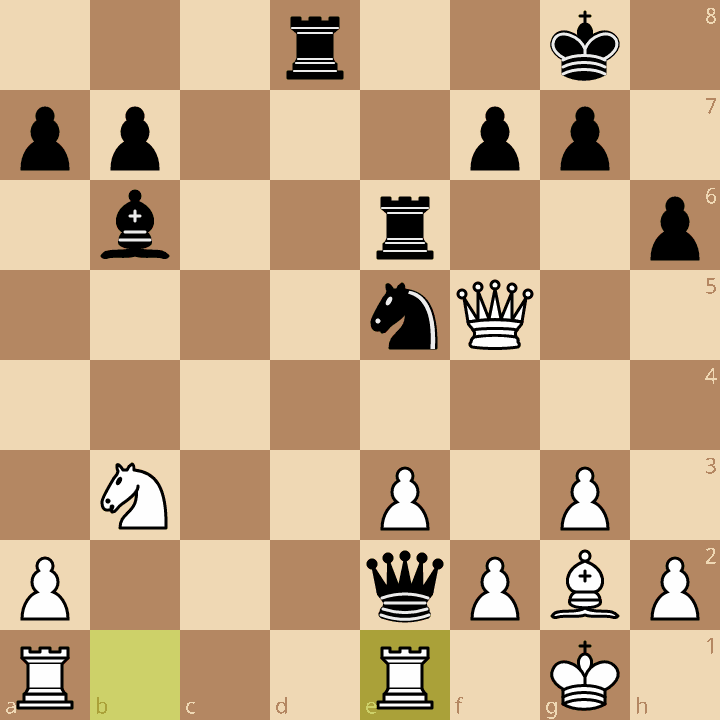

Game 3: Black vs 1606

This one featured a funny draw. It wasn’t quite best play by my opponent in this case, but also I felt the result was very understandable, and I was particularly plussed to have gotten a draw from an opening where I unintentionally sacrificed a pawn:

As it turns out here, the first move I suggested to myself was the correct one, and 5…e4 would continue down some theoretical line. Instead, not keen to play such a committal move in an opening that felt really tricky as it was, I decided I’d castle and deal with the complications later. 5…O-O(!?) 6.Nxb4 and only then did I realize I was losing my pawn on e5: 6…Nxb4 7.Nxe5. It turns out that Black actually gets close to sufficient compensation for this pawn: 7…Re8 8.d4 (retreating the knight runs into a smothered mate with 8…Nd6#!) d6 9.Nd3 Nc6.

Here my opponent went a little wrong, and played the move 10.d5?! After 10…Nd4, Black is again threatening a smothered mate, but this time on the f3-square! My opponent took some time then went for 11.Be3!, an only-move. I responded with 11…Nf5! Then my opponent thought for a while and then played 12.Bf4?! I had nothing better than 12…Nd4 renewing my threat. We ended up repeating and drew on the 15th move as we shuffled bishop and knight. But in fact, if my opponent chose g5 instead of f4 for his bishop, then after Nd4, he could respond with the move e3 and have a pleasant position up a pawn with no more difficulty getting castled. Alas, I got lucky.

My first win of the tournament was Round 2.

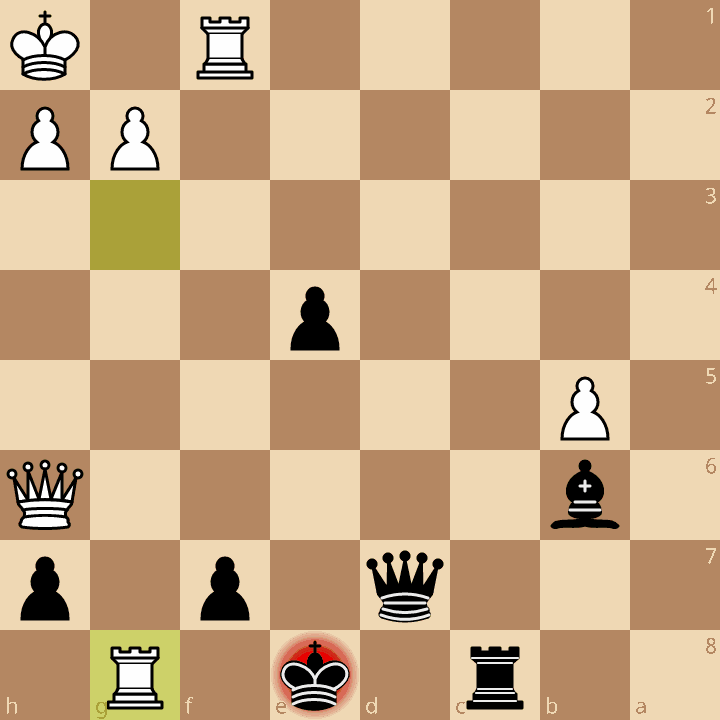

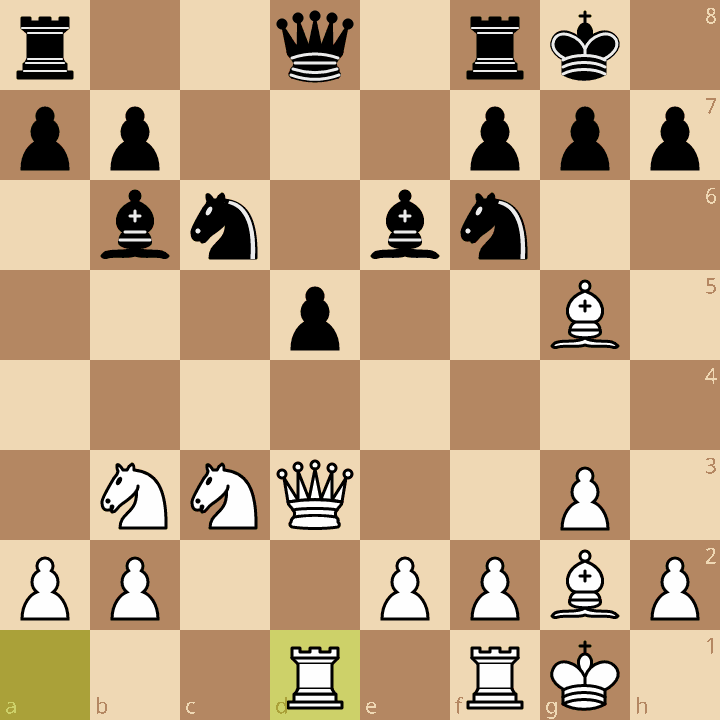

Game 2: White vs 1497

In this game I was, thanks to a blunder and depressed play on my opponent’s part, able to obtain not only a pawn but also the critical queen’s bishop early in the middlegame.

After this my opponent immediately lashed out with the move 14…d5?! It makes sense to try to complicate the position as much as possible when down material and strategically. After 15.cxd5 Nfxd5 16.Bb2 c4 17.e4!? c3 18.Rc1 my opponent found the interesting move 18.Bh6!?

Again, this move makes a lot of sense from Black’s perspective. I wasn’t completely sure I could take the knight on d5, since black would reload with the other knight and the c-pawn would be protected. Even though this position is still won for White according to the engine, I evaluated that it was complicated and unclear. The extra piece is nice, but with Black’s control over the c-file, it was uncomfortable and not particularly necessary anyways. So instead I calculated for a long time and played 19.Rc2 cxb2! I wasn’t sure that I would be able to prevent the promotion of the pawn if I took the sacrificed queen, because for some reason I didn’t see that I could quickly play Qb1. Instead, I declined the sacrifice of the queen and instead took the knight with 20.exd5. My opponent then executed a clever move to try to promote the pawn on b1. 20…Bc1!?

Here I had to think for a moment and regain my senses because for a moment I thought I was actually about to lose. But then I remembered the knight on f3. 21.Rxc8! Rfxc8 22.Nd2!

Now my opponent cannot promote the pawn. The game continued for another 14 or so moves, but with the knight on the promotion square and Black’s bishop the wrong color, all of Black’s plans were shut down and the mating attack came quickly.

At the end of day 1, I had a massive headache and a 1.5/4 score. But there was always the next day, and I came back refreshed and ready to play some more chess. On day 2, I got to play two nice English games in a row, and in fact the opening for both of them were the same variation for the first 7 or so moves.

Game 5: White vs 1388

Game 5 was a relatively simple win. My opponent voluntarily isolated his d-pawn, traded his bishop for a knight, and got into some development problems along the way thanks to the move 11…Nbd7

Despite the material balance, because of Black’s development and structure here, this position is by all intents and purposes won for White. White has the bishop pair, open lines for all the important pieces, the isolani on d5 is completely blockaded, and there are a lot of tactical threats involving Bf4-c7, not to mention the open c-file will go to White since Black can’t expediently vacate the c8 square before White gets a rook on c1. The main issue with this position is the extremely precarious situation with Black’s queen, who is already close to being trapped. After 12.Bf4 a6 I stared at the board for a long time to figure out if I could make this queen problem work to my advantage, but ended up doing what all the textbooks would tell you to do: put a rook on the open file! 13.Rac1! works great here so I decided to go with it.

For the record, my spider sense was tingling here with the moves 13.Bc7 Qe7 (13…Qe8 14.Bd6 and it’s lights out for the rook) 14.Nf5 Qe6 15.Bh3, but I could not find the follow-up after 15…Kh8 and the position would become very complicated needlessly.

It turns out that this line and Rac1 evaluate to about the same anyways according to Stockfish, so I’m glad I chose the more positional line and avoided the stress.

There were some other interesting moments in this game.

Here the game move 15.Bxe4! wins a pawn (either after dxe4, or Qxd4 Bxh7+!), but I still had to decide if I wanted to give up the king’s bishop while its counterpart on c8 still existed and would be able to attack my light squares. I determined that the pressure from that bishop would not be felt for a few moves because it was impossible to develop, and I had such positional pressure here that should more than compensate for the weaknesses on the light squares.

The last critical moment of the game was here:

In fact, many moves here are good, but I was looking for the best move since I felt I had every chance to win this game. In the end I went for the top move 22.Bd4! which actually set a bit of a trap for my opponent and would force a very favorable endgame wherein the d5 pawn’s terminal weakness would finally tell: 22…Rxc1 23.Rxc1 Qd2

Here it looks like Black is winning something, as the e2-pawn cannot be defended. However White can give up that pawn because they’ll get a mating attack instead. So I played 24.Qc3! completely consolidating the position. My opponent saw the writing on the wall and traded queens, not wanting to expose his king to the chill winds of a mating attack. This game was a very clear example of how playing the most intuitive moves on auto-pilot can lead to problems later. I was able to calculate to the above position and find 24.Qc3 on move 20, all based on my opponent’s pace and choice of moves during the whole game. I won the ensuing endgame no problem:

Overall it was a satisfying win.

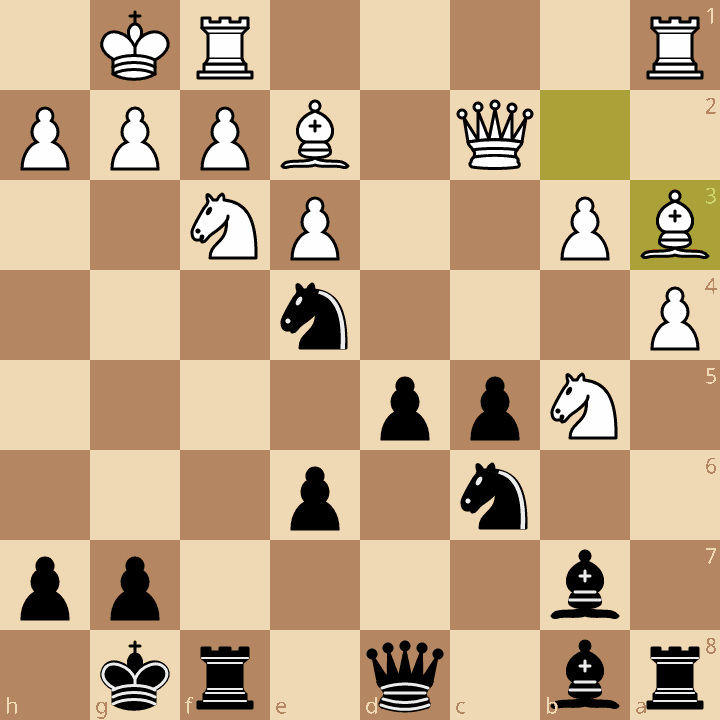

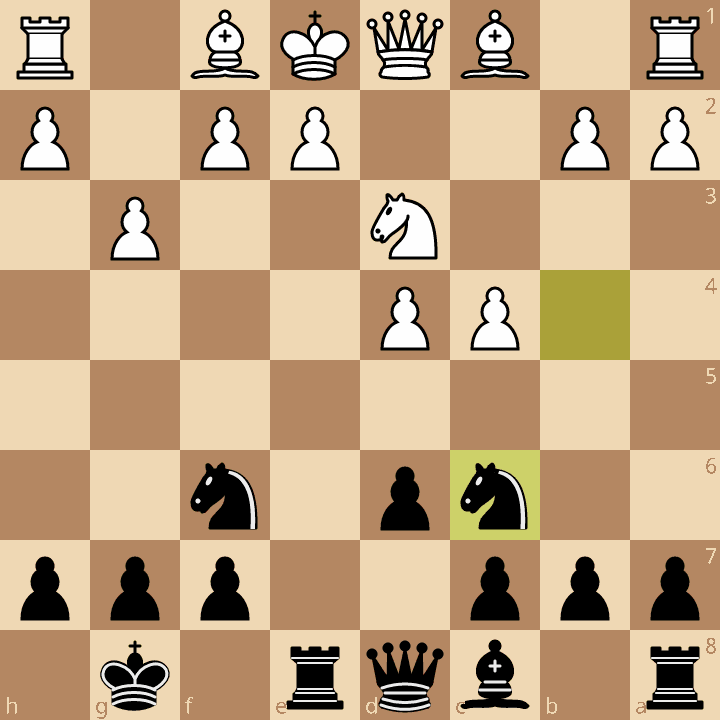

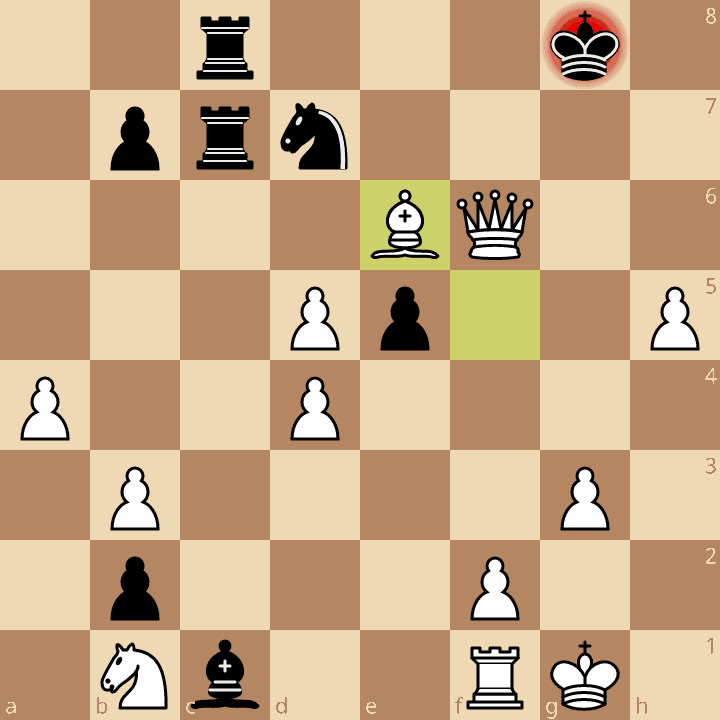

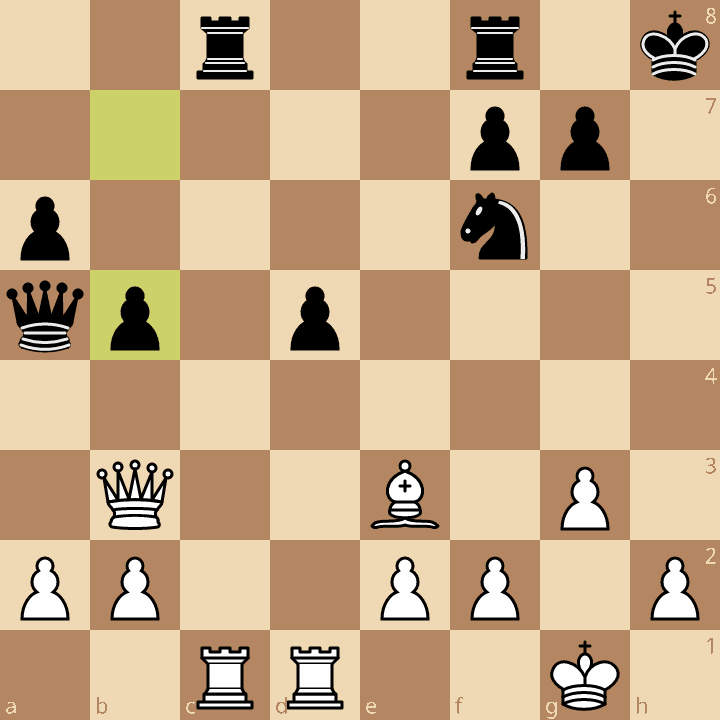

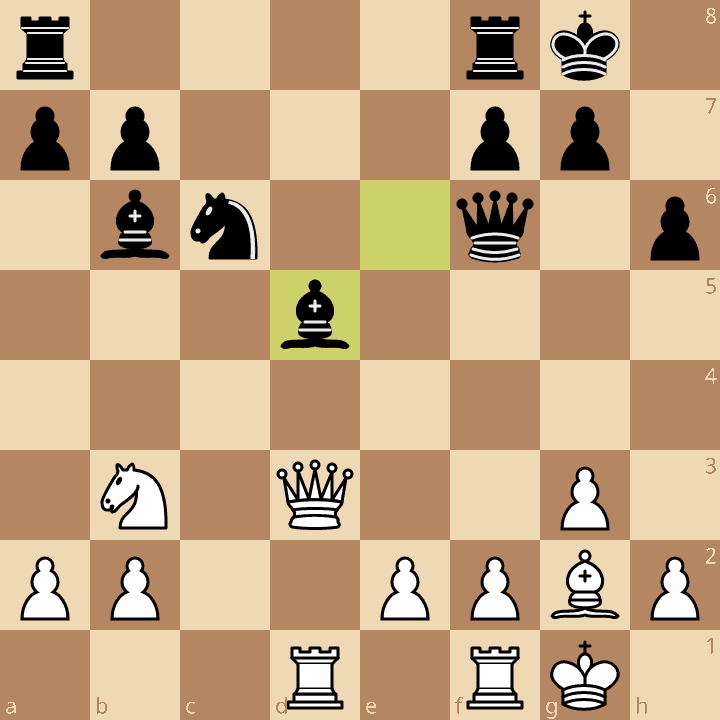

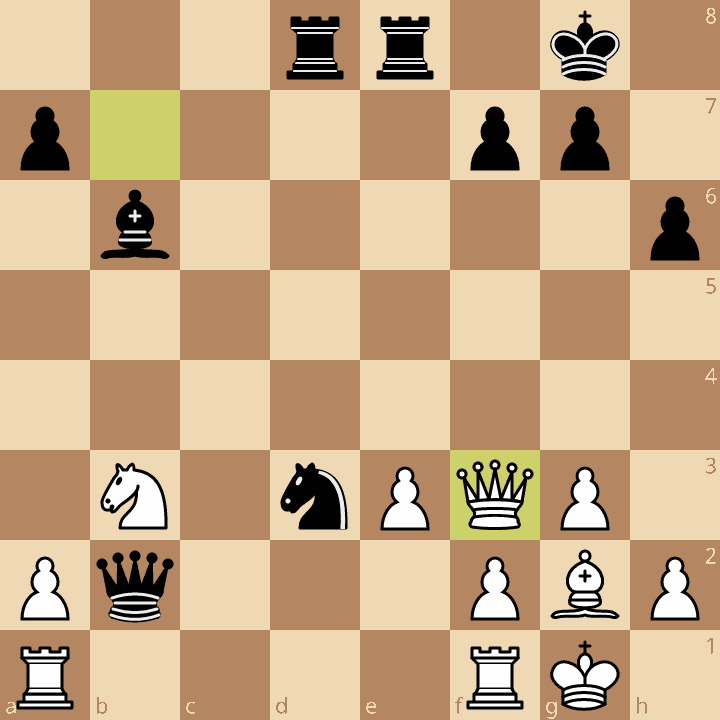

Game 6: White vs 1660

Game 6 featured a very similar variation to Game 5 in a Reversed Alapin, but my opponent played stronger moves and we ended up in this position:

Again, Black has an isolani, but this time it’s much more defended, and their pieces are activated very nicely on the sixth rank. Nevertheless d5 is still weak, and White has a lot of pressure on Black’s center which is about to collapse. Though this is a theoretical advantage for White, I was having a difficult time imagining how to make something of the position over the board, because I foresaw that my b2-pawn was going to drop in the future. I still have a lot of pressure, but it wasn’t by any means clear to me what the best continuation would be after my opponent’s move 13…h6

14.Bxf6 Qxf6 15.Nxd5 Bxd5

This was the position I was having a hard time deciding during my calculations. In the end I played the inferior 16.Qxd5, which allowed Black to equalize quickly with 16…Rad8 17.Qf3 Qxb2. The wind was taken out of my position’s sails, and I had to settle for the passive and equalizing 18.Ra1.

My main reason to avoid 16.Bxd5 was Black’s follow-up move 16…Nb4, and it felt rather strange to play the odd retreat 17.Qb1 and give up the powerful bishop to get the extra pawn. Even if White is up a pawn here, I felt that the open center disfavored my knight (who has no pawn-protected anchor points in the center to achieve an active position), and Black’s bishop was doing a nice job putting pressure against White’s center thanks to the influence on the f2 square. Alas, this position is a pawn for a pawn and Black’s compensation is perhaps just sufficient in the long run according to the engine. I’m not sure if this is a flaw in my thinking process or just human evaluation.

A few moves later, we reached this position and it wizened me up to Bxd5’s merits.

This ended up being a nice tactical calculation exercise. What is Black’s plan here after the move 20.Qxb7? I spent a while looking at this position (probably 15 or so minutes) and then played 20.Qf5. My idea was to activate the bishop into a more threatening position on the kingside. Either the e4 or d5 square were my main ideas. My opponent took more time to figure out how to follow up, and chose 20…Re6. After this I determined that Black’s threat was over and therefore attacked his queen with 21.Rfb1 Qe2 22.Re1 and offered a draw, since Black’s attack has run out of steam, and maybe the b7-pawn could drop in the future if he tried to play on. In either case, the play was killed. Once my opponent was convinced of this himself, he accepted it though perhaps somewhat reluctantly, and I went home happy with an even score.

But what if I had taken on b7? What convinced me this was a bad idea?

The combination of moves would have led to an endgame that was technically equal but appeared very unpleasant:

20.Qxb7 Nd3! 21.Qf3

Now Black can uncork a combination, and White has just enough tactical resources to survive.

21…Nxf2!! 22.Rxf2 Bxe3 23.Qxf3!! Qxa1+! 24.Nxa1 Rxe3 and we end up in a position where White has two pieces for a rook and pawn. This seemed extremely unpleasant with Black having so much control over the open files on the board, and this was enough to motivate me to find Qf5 instead of trying to take the pawn on b7. As it turns out, according to the computer, this position is even. But to my eye, Black has all the play, and it’s hard to make much out of this position for White in any case.

In the end, I scored 3/6 and gained about 20 rating points, which is another big gain for me since I’ve been climbing from an all-time low of 1511 achieved back in April this year. I’m now up to 1562 after four tournaments, and I’m very pleased. In some sense it feels like I’m getting back to the player I used to be(?)

In the larger picture, the event was a huge success for the Sacramento chess scene — too huge, since the report is that they’ll have to find a larger venue for the 2026 edition; 154 participants were too many to confine to the usual event room and they had to rent out another one last-minute! So a huge congratulations and thanks to the organizers of the event and especially to the tournament director John McCumiskey, without whom the 2025 Sacramento Chess Championship would not have been nearly as great as it was.

Until next time!

Great recap, Nick! I love that I got a mention at the beginning as well. :)